По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

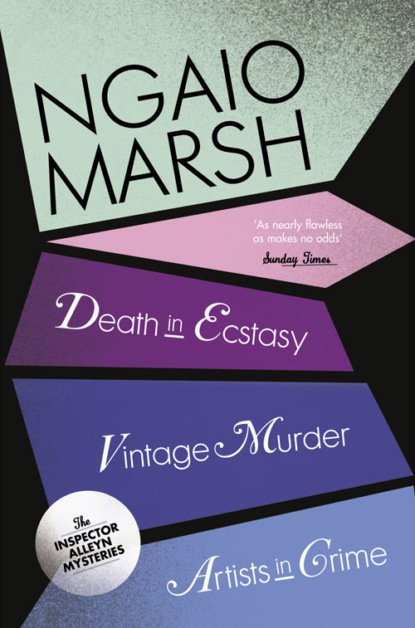

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 2: Death in Ecstasy, Vintage Murder, Artists in Crime

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Ah-ha,’ said Nigel.

‘No, not quite “Ah-ha” I fancy,’ murmured the inspector.

‘Hullo!’ exclaimed Fox suddenly.

‘What’s up?’ asked Alleyn.

‘Look here, sir.’ Fox came to the table and put down a small slip of paper.

‘I found it in the cigarette-box,’ he said. ‘It’s the lady again.’

‘Yes,’ agreed Alleyn, ‘it’s the lady. Bless my soul,’ he added, ‘the damn’ place is choc-a-bloc full of dubious correspondence.’

Nigel came across to look. Fox’s new find was a very small page of shiny paper. Monday’s date was printed in one corner and underneath was scribbled the word: ‘Sunday.’ Three edges were gilt, the fourth was torn across at an angle as though it had been wrenched from a book. Cara Quayne had written in pencil: ‘Must see you. Terrible discovery. After service tonight.’

‘Where exactly was it?’ asked Alleyn.

‘In this.’ Fox displayed an elaborate Benares box almost full of Turkish cigarettes. ‘It was on the sideboard and the paper lay on top of the cigarettes. Like this.’ He picked up the paper and put it in the box.

‘This is very curious,’ said Alleyn. He raised an eyebrow and stared fixedly at the little message. Get the deceased’s handbag,’ he said after a minute. ‘It’s out there.’

Fox went out and returned with a morocco handbag. Alleyn opened it and turned out the contents, and arranged them on the table. They were: A small case containing powder, a lipstick, a handkerchief, a purse, a pair of gloves, and a small pocket-book bound in red leather with a pencil attached.

‘That’s it,’ said Alleyn.

He opened the book and laid the note beside it. The paper corresponded exactly. He scribbled a word or two with the pencil.

‘That’s it,’ he repeated. ‘The lead is broken. There’s the same double line in each case.’ He turned the leaves of the book. Cara Quayne had written extensively in it – shopping lists, appointments, memoranda. The notes came to an end about half-way through. Alleyn read the last one and looked up quickly.

‘Got an evening paper, either of you?’

‘I have,’ said Fox, producing one, neatly folded, from his pocket.

‘Does the new show at the Criterion open tomorrow?’

‘You needn’t bother to look,’ interrupted Nigel. ‘It does.’

‘You have your uses,’ grunted the inspector. ‘That fixes it then. She wrote that note today.’

‘How do you know?’ demanded Nigel.

‘There is a note on today’s page: “Dine and go ‘Hail Fellow’ Criterion, Raoul, tomorrow.” I wanted to be sure she stuck to the printed date. The next page, tomorrow’s, is the one she tore out. There’s the date. She must have torn it out today.’

‘Things are looking up a bit, aren’t they, sir?’ ventured Fox.

‘Are they, Fox? Perhaps they are. And yet – it’s a sticky business, this. Light your pipe, my Foxkin, and do a bit of ‘teckery. What’s in your mind, you sly old box of tricks?’

Fox lit his pipe, sat down, and gazed solemnly at his superior.

‘Come on, now,’ said Alleyn.

‘Well, sir, it’s a bit early to speak anything like for sure, but say the lady knew what we know about that parcel there. Say she found it out today, when the parson was out – called in to see him perhaps.’

‘And found the safe open?’

‘Might be. Sounds kind of careless, but might be. Anyway, say she found out somehow and wanted to tell him. Say he came in, read the note, and – well, sir, say he thought something would have to be done about it.’

‘I don’t think he has read the note, Fox.’

‘Don’t you, sir?’

‘No. We can see if his prints are on it. If he has read it I don’t think he’s a murderer.’

‘Why not?’ asked Nigel.

‘He’d have destroyed it.’

‘That’s so,’ admitted Fox.

‘But,’ Alleyn went on, ‘as I say, I don’t think he’s read it. There are no cigarette-ends of that brand about, are there?’

They hunted round the room. Alleyn went into the bedroom and came back in a few moments.

‘None there,’ he said, ‘and dear Mr Garnette looks very unattractive with his mouth open. But I think we’d better look for prints in there, Bailey. There’s that open door. Did you run anything to earth in the bedroom, Fox?’

‘A very small trace of a powder in the wash-stand cupboard, sir. That’s all.’

‘Well, what about cigarette-butts?’

‘None here,’ announced Fox, who had examined the grate as well as all the ashtrays in the room. ‘There are several Virginians – Mr Bathgate’s and Dr Curtis’s I think they are – no Turkish anywhere.’

‘Then he hasn’t opened the box.’

‘I must say I can’t help thinking that note’s got a bearing on the case,’ said Fox.

‘I think you’re right, Fox. Put it in my bag, box and all. Let’s finish off and go home.’

‘And tomorrow?’ asked Nigel.

‘Tomorrow we’ll get Mr Garnette to open the surprise packet.’

‘What about the gentleman in question, sir?’

‘What about him?’

‘Will he be all right? All alone?’

‘Good heavens, Fox, what extraordinary solicitude! He’ll wake up with a hirsute tongue and a brazen belly. And he will be very, very troubled in his mind. There’s that back door.’