По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

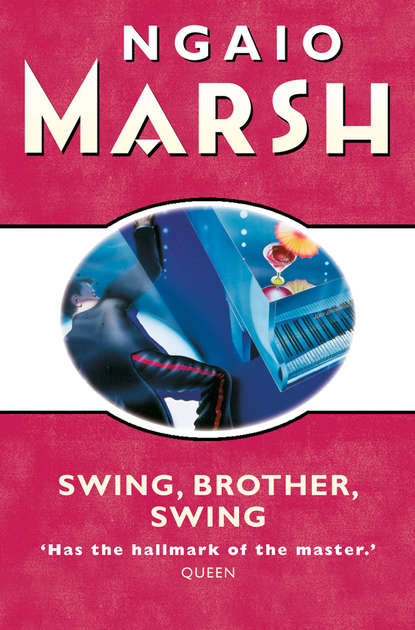

Swing, Brother, Swing

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I disagree entirely,’ Mr Rivera interposed. He rose gracefully. His suit was dove-grey with a widish pink stripe. Its shoulders seemed actually to curve upwards. He was bronzed. His hair swept back from his forehead and ears in thick brilliant waves. He had flawless teeth, a slight moustache and large eyes and he was tall. ‘I like the idea,’ he said. ‘It appeals to me. A little macabre, a little odd, perhaps, but it has something. I suggest, however, a slight alteration. It will be an improvement if, on the conclusion of Lord Pastern’s solo, I draw the rod and shoot him. He is then carried out and I go into my hot number. It will be a great improvement.’

‘Listen, Carlos –’

‘I repeat, a great improvement.’

The pianist laughed pointedly and the other grinned.

‘You make the suggestion to Lord Pastern,’ said the tympanist. ‘He’s going to be your ruddy father-in-law. Make it and see how it goes.’

‘I think we better do it like he says, Carl,’ said Mr Bellairs. ‘I think we better.’

The two men faced each other. Mr Bellairs’ expression of geniality had become habitual. He might have been a cleverly made ventriloquist’s doll with a pale rubber face that was constantly and arbitrarily creased in a roguish grimace. His expressionless eyes with their large pale irises and enormous pupils might have been painted. Wherever he went, whenever he spoke, his lips parted and disclosed his teeth. Two dimples grooved his full cheeks, the flesh creased at the corners of his eyes. Thus, hour after hour, he smiled at the couples who danced slowly past his stand; smiled and bowed and beat the air and undulated and smiled. He sweated profusely from these exertions and at times would mop his face with a snowy handkerchief. And behind him every night his Boys, dressed in soft shirts and sculptured dinner-jackets with steel pointed buttons and silver revers, flexed their muscles and inflated their lungs in obedience to the pulse of his celebrated miniature baton of chromium-tipped ebony, presented to him by a lady of title. Great use was made of chromium at the Metronome by Breezy’s Boys. Their instruments glittered with it, they wore wrist-watches on chromium bracelets, the band-title appeared in chromium letters on the piano which was painted in aluminium to resemble chromium. Above the Boys, a giant metronome, outlined in coloured lights, swung its chromium-tipped pendulum in the same measure. ‘Hi-dee-ho-dee-oh,’ Mr Bellairs would moan. ‘Gloomp-gloomp, giddy-iddy, hody-oh-do.’ For this and for the way he smiled and conducted his band he was paid three hundred pounds a week by the management of the Metronome, and out of that he paid his Boys. He was engaged with an augmented band for charity balls, and sometimes for private dances. ‘It was a grand party,’ people would say, ‘they had Breezy Bellairs and everything.’ In his world he was a big noise.

His Boys were big noises. They were all specialists. He had selected them with infinite pains. They were chosen for their ability to make the hideous and extremely difficult rumpus known as The Breezy Bellairs Manner and for the way they looked while they made it. They were chosen because of their sex appeal and their endurance. Breezy said: ‘The better they like you the more you got to give.’ Some of his players he could replace fairly easily; the second and third saxophonists and the double-bass, for instance, but Happy Hart, the pianist and Syd Skelton the tympanist and Carlos Rivera the piano accordionist, were, he said and believed, the Tops. It was a constant nagging anxiety to Breezy that some day, before his public had had Happy or Syd or Carlos, one or all of them might get hostile or fed up or something, and leave him for The Royal Flush Swingsters or Bones Flannagan and His Merry Mixers or The Percy Personalities. So he was always careful how he handled these three.

He was being careful now, with Carlos Rivera. Carlos was good. His piano accordion talked in The Big Way. When his engagement to Félicité de Suze was announced it’d be A Big Build-up for Breezy and the Boys. Carlos was as good as they come.

‘Listen, Carlos,’ Breezy urged feverishly. ‘I got an idea. Listen, how about we work it this way? How about letting his lordship fire at you like what he wants and miss you. See? He looks surprised and goes right ahead pulling the trigger and firing and you go right ahead in your hot number and every time he fires, one of the other boys acts like he’s been hit and plays a queer note and how about these boys playing a note each down the scale? And you just smile and sign off and bow kind of sardonically and leave him flat? How about that, boys?’

‘We-ell,’ said the Boys judicially.

‘It is a possibility,’ Mr Rivera conceded.

‘He might even wind up by shooting himself and getting carried off with the wreath on his breast.’

‘If somebody else doesn’t get in first,’ grunted the tympanist.

‘Or he might hand the gun to me and I might fire it at him and it might be empty, and he might go into his act and end up with a funny faint and get carried out.’

‘I repeat,’ Rivera said, ‘it is a possibility. We shall not quarrel in this matter. Perhaps I may speak to Lord Pastern myself.’

‘Fine!’ Breezy cried, and raised his tiny baton. ‘That’s fine. Come on, boys. What are we waiting for? Is this a practice or is it a practice? Where’s this new number? Fine! On your marks. Everybody happy? Swell. Let’s go.’

III

‘“Carlisle Wayne,” said Edward Manx, ‘“was thirty years old, but she retained something of the air of adolescence, not in her speech, for that was tranquil and assured, but in her looks and manner. Her movements were fluid; boyish perhaps. She had long legs, slim hands and a thin beautiful face. Her clothes were wisely chosen and gallantly worn but she took no great trouble with them and seemed to be well-dressed rather by accident than design. She liked travel but dreaded sight-seeing and would retain memories as sharp as pencil drawings of unimportant details; a waiter, a group of sailors, a woman in a bookstall. The names of the streets or even the towns where these persons had been encountered would often be lost to her; it was people in whom she was really interested. For people she had an eye as sharp as a needle and she was extremely tolerant.”’

‘“Her remote cousin, The Honourable Edward Manx,”’ Carlisle interrupted, ‘“was a dramatic critic. He was thirty-seven years old and of romantic appearance but not oppressively so. His professional reputation for rudeness was cultivated with some pains for, although cursed with a violent temper, he was by instinct of a courteous disposition!”’

‘Gatcha!’ said Edward Manx, turning the car into the Uxbridge Road.

‘“He was something of a snob but sufficiently adroit to disguise this circumstance under a show of social indiscrimination. He was unmarried –”’

‘“having a profound mistrust of those women who obviously admired him –”’

‘“– and a dread of being rebuffed by those of whom he was not quite sure.”’

‘You are as sharp as a needle you know,’ said Manx, uncomfortably.

‘Which is probably why I, too, have remained unmarried.’

‘I wouldn’t be surprised. All the same I’ve often wondered –’

‘I invariably click with such frightful men.’

‘Lisle, how old were we when we invented this game?’

‘“Novelettes?” Wasn’t it in the train when we came back from our first school holidays with Uncle George? He wasn’t married then so it must have been over sixteen years ago. Félicité was only two when Aunt Cecile married him and she’s eighteen now.’

‘It was then. I remember you began by saying: “There was once a very conceited, bad-tempered boy called Edward Manx. His elderly cousin, a peculiar peer –”’

‘Even in those days, Uncle George was prime material, wasn’t he?’

‘Lord, yes! Do you remember –’

They told each other anecdotes, familiar to both, of Lord Pastern and Bagott. They recalled his first formidable row with his wife, a distinguished Frenchwoman of great composure who came to him as a widow with a baby daughter. Lord Pastern, three years after their marriage, became an adherent of a sect that practised baptism by total immersion. He wished his stepdaughter to be rechristened by this method in a sluggish and eel-infested stream that ran through his country estate. Upon his wife’s refusal he sulked for a month and then, without warning, took ship to India where he immediately succumbed to the more painful austerities of the yogi. He returned to England, loudly proclaiming that almost everything was an illusion and, going by stealth to his stepdaughter’s nursery, attempted to fold her infant limbs into esoteric postures, exhorting her, at the same time, to bend her gaze upon her navel and say ‘Om’. Her nurse objected, was given notice by Lord Pastern and reinstated by his wife. A formidable scene ensued.

‘My Mama was there, you know,’ said Carlisle. ‘She was supposed to be Uncle George’s favourite sister but she made no headway at all. She and Aunt Cecile held an indignation meeting with the nanny in the boudoir, and Uncle George sneaked down the servants’ stairs with Félicité and drove her thirty miles in his car to some sort of yogi boarding-house. They had to get the police to find them. Aunt ‘Cile laid a charge of kidnapping.’

‘That was the first time Cousin George became banner headlines in the press,’ Edward observed.

‘The second time was the nudist colony.’

‘True. And the third was the near-divorce.’

‘I was away for that,’ Carlisle observed.

‘You’re always going away. Here I am, a hard-working pressman who ought to be in constant transit to foreign parts, and you’re the one to go away. He was taken with the doctrine of free love, you remember, and asked a number of rather odd women down to Clochemere. Cousin Cecile at once removed with Félicité, who was by now twelve years old, to Duke’s Gate, and began divorce proceedings. But it turned out that Cousin George’s love was only free in the sense that he delivered innumerable lectures without charge to his guests and then told them to go away and get on with it. So the divorce fell through, but not before counsel and bench had enjoyed an orgy of wisecracks and the press had exhausted itself.’

‘Ned,’ Carlisle asked, ‘do you imagine that it’s at all hereditary?’

‘His dottiness? No, all the other Settinjers seem to be tolerably sane. No, I fancy Cousin George is a sport. A sort of monster, in the nicest sense of the word.’

‘That’s a comfort. After all I’m his blood-niece, if that’s the way to put it. You’re only a collateral on the distaff side.’

‘Is that a cheap sneer, darling?’

‘I wish you’d put me wise to the current set-up. I’ve had some very queer letters and telegrams. What’s Félicité up to? Are you going to marry her?’

‘I’ll be damned if I do,’ said Edward with some heat. ‘It’s Cousin Cecile who thought that one up. She offered to house me at Duke’s Gate when my flat was wrested from me. I was there for three weeks before I found a new one and naturally I took Fée out a bit and so on. It now appears that the invitation was all part of a deep-laid plot of Cousin Cecile’s. She really is excessively French, you know. It seems that she went into a sort of state-huddle with my mama and talked about Félicité’s dot and the desirability of the old families standing firm. It was all terrifically Proustian. My mama, who was born in the colonies and doesn’t like Félicité, anyway, kept her head and preserved an air of impenetrable grandeur until the last second when she suddenly remarked that she never interfered in my affairs and wouldn’t mind betting I’d marry an organizing secretary in the Society for Closer Relations with Soviet Russia.’

‘Was Aunt Cile at all rocked?’

‘She let it pass as a joke in poor taste.’

‘What about Fée, herself?’

‘She’s in a great to-do about her young man. He, I don’t mind telling you, is easily the nastiest job of work in an unreal sort of way that you are ever likely to encounter. He glistens from head to foot and is called Carlos Rivera.’