По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

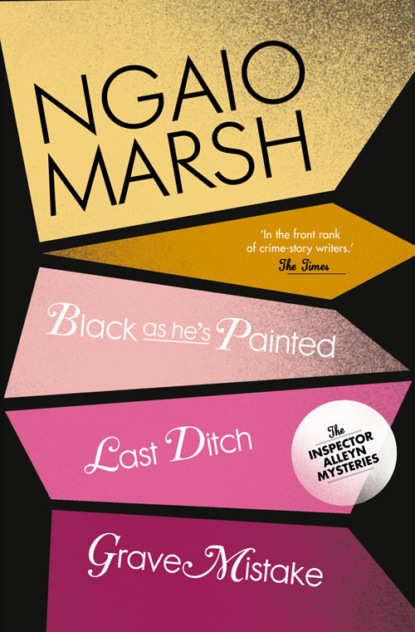

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 10: Last Ditch, Black As He’s Painted, Grave Mistake

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

And Alleyn experienced a swift upsurge of an emotion that he would have been hard put to it to define. ‘Do you Boomer?’ he said, ‘I believe you do.’

‘A fraction more to your left,’ said Troy. ‘Rory – if you could move your chair. That’s done it. Thank you.’

The Boomer patiently maintained his pose and as the minutes went by he and Alleyn had little more to say to each other. There was a kind of precarious restfulness between them.

Soon after half past six Troy said she needed her sitter no more for the present. The Boomer behaved nicely. He suggested that perhaps she would prefer that he didn’t see what was happening. She came out of a long stare at her canvas, put her hand in his arm and led him round to look at it, which he did in absolute silence.

‘I am greatly obliged to you,’ said The Boomer at last.

‘And I to you,’ said Troy. ‘Tomorrow morning, perhaps? While the paint is still wet?’

‘Tomorrow morning,’ promised The Boomer. ‘Everything else is cancelled and nothing is regretted,’ and he took his leave.

Alleyn escorted him to the studio door. The mlinzi stood at the foot of the steps. In descending Alleyn stumbled and lurched against him. The man gave an indrawn gasp, instantly repressed. Alleyn made remorseful noises and The Boomer, who had gone ahead, turned round.

Alleyn said: ‘I’ve been clumsy. I’ve hurt him. Do tell him I’m sorry’

‘He’ll survive!’ said The Boomer cheerfully. He said something to the man, who walked ahead into the house. The Boomer chuckled and laid his massive arm across Alleyn’s shoulders.

He said: ‘He really has a fractured collar-bone, you know. Ask Doctor Gomba or, if you like, have a look for yourself. But don’t go on concerning yourself over my mlinzi. Truly, it’s a waste of your valuable time.’

It struck Alleyn that if it came to being concerned, Mr Whipplestone and The Boomer in their several ways were equally worried about the well-being of their dependants. He said: ‘All right, all right. But it’s you who are my real headache. Look, for the last time, I most earnestly beg you to stop taking risks. I promise you, I honestly believe that there was a plot to kill you last night and that there’s every possibility that another attempt will be made.’

‘What form will it take do you suppose? A bomb?’

‘And you might be right at that. Are you sure, are you absolutely sure, there’s nobody at all dubious in the Embassy staff? The servants –’

‘I am sure. Not only did your tedious but worthy Gibson’s people search the Embassy but my own people did, too. Very, very thoroughly. There are no bombs. And there is not a servant there who is not above suspicion.’

‘How can you be so sure! If, for instance, a big enough bribe was offered –’

‘I shall never make you understand, my dear man. You don’t know what I am to my people. It would frighten them less to kill themselves than to touch me. I swear to you that if there was a plot to kill me, it was not organized or inspired by any of these people. No!’ he said and his extraordinary voice sounded like a gong. ‘Never! It is impossible. No!’

‘All right. I’ll accept that so long as you don’t admit unknown elements, you’re safe inside the Embassy. But for God’s sake don’t go taking that bloody hound for walks in the Park.’

He burst out laughing, ‘I am sorry,’ he said, actually holding his sides like a clown, ‘but I couldn’t resist. It was so funny. There they were, so frightened and fussed. Dodging about, those big silly men. No! Admit! It was too funny for words.’

‘I hope you find this evening’s security measures equally droll.’

‘Don’t be stuffy,’ said The Boomer. ‘Would you like a drink before you go?’

‘Very much, but I think I should return.’

‘I’ll just tell Gibson.’

‘Where is he?’

‘In the study. Damping down his frustration. Will you excuse me?’

Alleyn looked round the study door. Mr Gibson was at ease with a glass of beer at his elbow.

‘Going,’ Alleyn said.

He rose and followed Alleyn into the hall.

‘Ah!’ said The Boomer graciously. ‘Mr Gibson. Here we go again, don’t we, Mr Gibson?’

‘That’s right, your Excellency,’ said Gibson tonelessly. ‘Here we go again. Excuse me.’

He went out into the street, leaving the door open.

‘I look forward to the next sitting,’ said The Boomer, rubbing his hands. ‘Immeasurably, I shall see you then, old boy. In the morning? Shan’t I?’

‘Not very likely, I’m afraid.’

‘No?’

‘I’m rather busy on a case,’ Alleyn said politely. ‘Troy will do the honours for both of us, if you’ll forgive me.’

‘Good, good, good!’ he said genially. Alleyn escorted him to the car. The mlinzi opened the door with his left hand. The police car started up its engine and Gibson got into it. The Special Branch men moved. At the open end of the cul-de-sac a body of police kept back a sizeable crowd. Groups of residents had collected in the little street.

A dark, pale and completely bald man, well-dressed in formal clothes, who had been reading a paper at a table outside the little pub, put on his hat and strolled away. Several people crossed the street. The policeman on duty asked them to stand back.

‘What is all this?’ asked The Boomer.

‘Perhaps it has escaped your notice that the media has not been idle. There’s a front page spread with banner headlines in the evening papers.’

‘I would have thought they had something better to do with the space.’ He slapped Alleyn on the back. ‘Bless you,’ he roared. He got into the car, shouted, ‘I’ll be back at half past nine in the morning. Do try to be at home,’ and was driven off. ‘Bless you,’ Alleyn muttered to the gracious salutes The Boomer had begun to turn on for the benefit of the bystanders. ‘God knows you need it.’

The police car led the way, turning off into a side exit which would bring them eventually into the main street. The Ng’ombwanan car followed it. There were frustrated manifestations from the crowd at the far end which gradually dispersed. Alleyn, full of misgivings, went back to the house. He mixed two drinks and took them to the studio, where he found Troy still in her painting smock, stretched out in an armchair scowling at her canvas. On such occasions she always made him think of a small boy. A short lock of hair overhung her forehead, her hands were painty and her expression brooding. She got up, abruptly, returned to her easel and swept down a black line behind the head that started up from its tawny surroundings. She then backed away towards him. He moved aside and she saw him.

‘How about it?’ she asked.

‘I’ve never known you so quick. It’s staggering.’

‘Too quick to be right?’

‘How can you say such a thing? It’s witchcraft.’

She leant against him. ‘He’s wonderful,’ she said. ‘Like a symbol of blackness. And there’s something – almost desperate. Tragic? Lonely? I don’t know. I hope it happens on that thing over there.’

‘It’s begun to happen. So we forget the comic element?’

‘Oh that! Yes, of course, he is terribly funny. Victorian music-hall, almost. But I feel it’s just a kind of trimming. Not important. Is that my drink?’

‘Troy, my darling, I’m going to ask you something irritating.’

She had taken her drink to the easel and was glowering over the top of her glass at the canvas. ‘Are you?’ she said vaguely. ‘What?’