По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

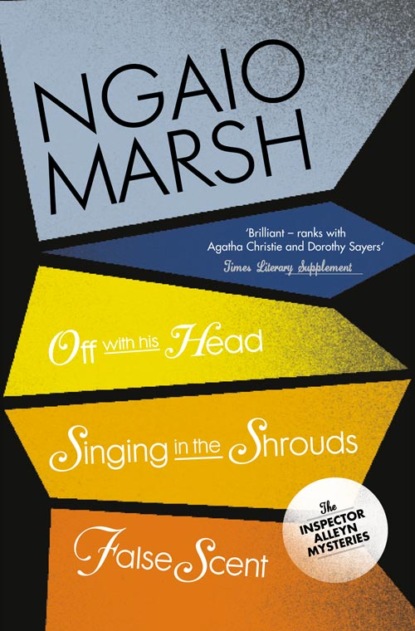

Inspector Alleyn 3-Book Collection 7: Off With His Head, Singing in the Shrouds, False Scent

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I’ll be bound she did. I didn’t imagine you people nowadays had much time for ritual dancing. Too “folksy”– is that the word? – or “artsy-craftsy” or “chi-chi”. No?’

‘Ah no! Not the genuine article like this one,’ Camilla protested. ‘And I’m sort of specially interested because I’m working at a drama school.’

‘Are you now?’

Dr Otterly glanced at the Andersens but they were involved in a close discussion with Simon Begg. ‘And what does the Guiser say to that?’ he asked and winked at Camilla.

‘He’s livid.’

‘Ha! And what do you propose to do about it? Defy him?’

Camilla said: ‘Do you know, I honestly didn’t think anybody was left who thought like he does about the theatre. He quite pitched into me. Rather frightening when you come to think of it.’

‘Frightening? Ah!’ Dr Otterly said quickly. ‘You don’t really mean that. That’s contemporary slang, I dare say. What did you say to the Guiser?’

‘Well, I didn’t quite like,’ Camilla confided, ‘to point out that after all he plays the lead in a pagan ritual that is probably chock full of improprieties if he only knew it.’

‘No,’ agreed Dr Otterly drily, ‘I shouldn’t tell him that if I were you. As a matter of fact, he’s a silly old fellow to do it at all at his time of life. Working himself into a fizz and taxing his ticker up to the danger-mark. I’ve told him so but I might as well speak to the cat. Now, what do you hope to do, child? What rôles do you dream of playing? Um?’

‘Oh, Shakespeare if I could. If only I could.’

‘I wonder. In ten years’ time? Not the giantesses, I fancy. Not the Lady M. nor yet The Serpent of Old Nile. But a Viola, now, or – what do you say to a Cordelia?’

‘Cordelia?’ Camilla echoed doubtfully. She didn’t think all that much of Cordelia.

Dr Otterly contemplated her with evident amusement and adopted an air of cosy conspiracy.

‘Shall I tell you something? Something that to me at least is immensely exciting? I believe I have made a really significant discovery: really significant about – you’d never guess – about Lear. There now!’ cried Dr Otterly with the infatuated glee of a White Knight. ‘What do you say to that?’

‘A discovery?’

‘About King Lear. And I have been led to it, I may tell you, through playing the fiddle once a year for thirty years at the Winter Solstice on Sword Wednesday for our Dance of the Five Sons.’

‘Honestly?’

‘As honest as the day. And do you want to know what my discovery is?’

‘Indeed I do.’

‘In a nutshell, this; here, my girl, in our Five Sons is nothing more nor less than a variant of the Basic Theme: Frazer’s theme: The King of the Wood, The Green Man, The Fool, The Old Man Persecuted by his Young: the theme, by gum, that reached its full stupendous blossoming in Lear. Do you know the play?’ Dr Otterly demanded.

‘Pretty well, I think.’

‘Good. Turn it over in your mind when you’ve seen the Five Sons, and if I’m right you’d better treat that old grandpapa of yours with respect, because on Sword Wednesday, child, he’ll be playing what I take to be the original version of King Lear. There now!’

Dr Otterly smiled, gave Camilla a little pat and made a general announcement.

‘If you fellows want to practise,’ he shouted, ‘you’ll have to do it now. I can’t give you more than half an hour. Mary Yeoville’s in labour.’

‘Where’s Mr Ralph?’ Dan asked.

‘He rang up to say he might be late. Doesn’t matter, really. The Betty’s a freelance after all. Everyone else is here. My fiddle’s in the car.’

‘Come on, then, chaps,’ said old William. ‘Into the barn.’ He had turned away and taken up a sacking bundle when he evidently remembered his granddaughter.

‘If you bean’t too proud,’ he said, glowering at her, ‘you can come and have a tell up to Copse Forge tomorrow.’

‘I’d love to. Thank you, Grandfather. Good luck to the rehearsal.’

‘What sort of outlandish word’s that? We’re going to practise.’

‘Same thing. May I watch?’

‘You can not. ’Tis men’s work, and no female shall have part nor passel in it.’

‘Just too bad,’ said Begg, ‘isn’t it, Miss Campion? I think we ought to jolly well make an exception in this case.’

‘No. No!’ Camilla cried, ‘I was only being facetious. It’s all right, Grandfather. Sorry. I wouldn’t dream of butting in.’

‘Doan’t go nourishing and ’citing thik old besom, neither.’

‘No, no, I promise. Goodnight, everybody.’

‘Goodnight, Cordelia,’ said Dr Otterly.

The door swung to behind the men. Camilla said goodnight to the Plowmans and climbed up to her room. Tom Plowman went out to the kitchen.

Trixie, left alone, moved round into the bar-parlour to tidy it up. She saw the envelope that Camilla in the excitement of opening her letter had let fall.

Trixie picked it up and, in doing so, caught sight of the superscription. For a moment she stood very still, looking at it. The tip of her tongue appearing between her teeth as if she thought to herself: ‘This is tricky.’ Then she gave a rich chuckle, crumpled the envelope and pitched it into the fire. She heard the door of the Public Bar open and returned there to find Ralph Stayne staring unhappily at her.

‘Trixie –’

‘I reckin,’ Trixie said, ‘you’m thinking you’ve got yourself into a terrible old pickle.’

‘Look – Trixie –’

‘Be off,’ she said.

‘All right. I’m sorry.’

He turned away and was arrested by her voice, mocking him.

‘I will say, however, that if she takes you, she’ll get a proper man.’

III

In the disused barn behind the pub, Dr Otterly’s fiddle gave out a tune as old as the English calendar. Deceptively simple, it bounced and twiddled, insistent in its reiterated demand that whoever heard it should feel in some measure the impulse to jump.