По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

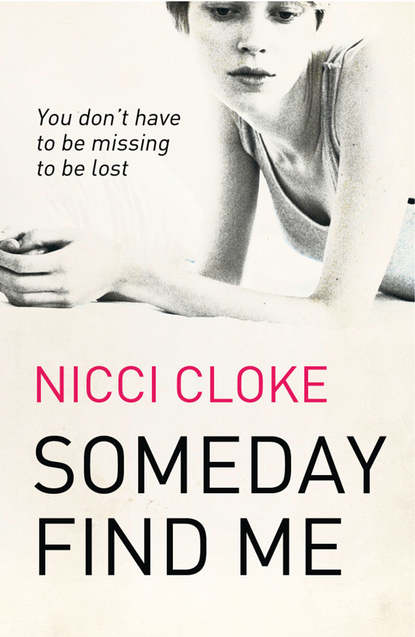

Someday Find Me

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She smiled but it was all weak and pretend and her face looked droopy and she was chewing at her lips, mashing them against her little white teeth. I picked her and her handbag up and she put her hands round my neck and nuzzled into me. By the time I got to the bottom of the stairs her eyes were gone again.

SAFFY

Sometimes, if you stare at something for long enough, you can make it into whatever you like. You can do it with the clouds in the sky, you can do it with the Artex on a ceiling, you can do it with shadows on the ground. You can do it with swirls in the snow and ripples in wet sand.

I stared at myself for years and years and the things I saw never changed.

As morning came, I lay on the bed looking up at the ceiling. I was waiting patiently to see if pictures would form, willing the lines and swirls to show me a story. I hadn’t been to sleep yet, even though Fitz was flat out in a contagious kind of floppy sleep, warmth and dreams wafting off him into the room. The room looked so glaringly dirty and dusty, mould spots speckling all the walls brown and green. I wondered why we never cleaned more. The skirting-boards were thick with scum and the light fixture had a rust-coloured tidemark around it, left over after a leak from the flat upstairs months before.

Everything seemed to be running away from me, the longer I looked, as though new layers of dirt and decay were forming right in front of me. I could see mould crawling over the walls, taking over everything. The TV would explode and my laptop would stop working. Quin’s copy of Brideshead would become all bloated and misshapen, pages soft and mildewed. All our clothes would get wet and putrid, even my favourite dress, which lay on a chair from Fitz undressing me the night before. I knew it was getting damp even then, all scrunched up and abandoned.

I looked away, back to the ceiling, but the dress kept flashing into my mind, brown spots over its lace. It was happening at that second, the fabric drawing moisture out of the air and soaking it up like a gorgeous frothy sponge, and I was going to end up like some poor man’s Miss Havisham in my Miss Selfridge dress and my forgotten flat. I leapt up and grabbed the dress, clutching it to my chest. My head was spinning and the fabric felt far away between my fingers. I slipped it onto a hanger and tucked it carefully between two others in the wardrobe – not between jeans, in case they left a blue stain – and made sure it was hanging down straight so mould couldn’t form in the creases. I squeezed some of the other dresses hanging there, the blue denim pinafore and the pale pink tea dress and the polka-dotted one with the sticky-out skirt, and they felt wet. Everything felt wet suddenly, even my hair and my scalp. And they felt cold, but maybe it was my hands that were cold. I wondered how you could ever tell. How could we ever know whether it was our hands that were cold, or wet, or hot, or dusty, or the thing they were touching? Do we make things happen or do they happen to us? I walked out into the living room, feeling the carpet soggy between my toes.

I liked silence in the house sometimes. On days like those, it was a soft silence that you could almost reach out and touch. It was peaceful; the house and I were at peace because he was there, sleeping. Everything was in its place.

Quin’s duvet was turned back and his pillow still had the oily dip where his head had been. He spent a lot of time away from the flat, but it didn’t matter: the room felt warm and safe even with just his things in it. Quin and I were like two leftover bits of the same puzzle. We fitted together even though we were misfits. I straightened out his sleeping bag and smoothed down the duvet, making his corner nice for him.

The rest of the room was tidy, everything put away. I stood in the middle and looked around. Though I tried to pull away, the corner kept calling me back.

The canvases were stacked neatly against the wall, backs to me. The papers and loose sketches were piled carefully underneath the desk. My sketchbooks sat on the desk, big, medium and small fitting one inside another. I sat down in the foldout chair and ran my finger along the edge of each one. I liked the way they lay together like this and looked like a shrinking version of one item, the stages laid out for you to see; the large original to the perfect miniature. I took the small one down and opened it, letting the fat cover flop over on its spirals. Here are the things that lived inside:

Portrait of a Lady. Picture of Fate Jones torn out of the free paper and taped in. Pencil question mark across left half of page.

True Love Never Dies. Still-life of a bed of roses with a junkie lying among the flowers – work in progress.

Outline of arm, three unfinished flowers. Half-page torn out.

Things I’ll Never Say. Crying child. Half a head of hair, one eye, unshaded lips, outline of nose. Jagged biro line through centre of page.

Untitled # 1. Blue dots of paint, flicked with the edge of a paintbrush. Work in no progress.

Untitled # 2. Circle drawn with black kohl. Artist’s intention unknown.

Stick Man Feels Sad. As described.

Self-portrait #1. Blank page, faint traces of pink eraser over surface of page.

As I turned the pages, I felt my skin begin to creep and crawl with all of the feelings that couldn’t get out and swirled half-formed and stormy. I grabbed hold of the pages, tore them out and slammed the notebook against the wall. It slid down all the way and when it reached the carpet it tipped over sheepishly. I grabbed a handful of my hair and pulled that instead. I felt the newly shorn shortness, the uneven patches and the way it brushed my shoulders where before it had trailed down my back, and I remembered it in a rush. How the day before had started and how the party had ended. I started at the start and I thought it all through carefully like I was remembering a dream.

The silence in the house had been too loud for words that morning. It always was just after he left, as the sound of him loping up the stairs and across the pavement above me faded away. Sometimes there’d be the tinkle and fumble of him dropping his keys or his apron and bending down to pick them up, a quick flash of his thin fingers in the tiny strip of window and then he’d be gone. I had dropped the towel and stepped one foot, two feet naked across the little hall. The carpet had felt thin and cold between my toes, and the hairs on my arms stood up in a thick fuzz. I rubbed them hard to get rid of it and stepped carefully into the bedroom. Everything felt slow and dizzy, as if all the sounds had gone out of the flat with Fitz and I was left trying to balance in an empty room off-kilter and unsteady.

I’d stood in front of the cracked half of mirror, which was propped against the wall. It had been full-length, once, if you balanced it at the right angle and stood far enough back, but one night when we were drunk and silly and happy and kissing the kind of kisses you can’t stop, when you keep raining kisses like butterflies on each other until you can’t breathe any more, we’d stumbled into it and smashed it right in half. I had been frightened at the time that it was bad luck, that maybe we’d be cursed, but Fitz had said that if you didn’t look in the pieces you were all right. And so I’d sat on the end of the bed as he picked up each of the pieces, looking at the ceiling the whole time and humming, because he always did that when things were good or okay, and there was one piece left, almost a whole half, which wasn’t cracked, so we kept that.

Looking at it then, alone and quiet, I’d wondered if we had been cursed all along. A draught blew in from the hall and I shivered, trying to shake the thought out. I turned away and went to the wardrobe. I ran the clothes hanging there between my fingers, denims and jumpers and soft dresses. When I looked down, my favourite lacy dress was in my hand. That happened sometimes; I’d told Fitz once that it must like going out, but secretly I wondered if sometimes I made it jump out of the wardrobe just by thinking it.

I’d pulled the lovely, frothy loveliness of it over my head and wiggled it down. Kneeling back in front of the mirror, I drew on fat lines of black liner without really looking at my face. I stuffed my hair up into a kind of knot and stuck some pins in to hold it up, and then I fluffed at my fringe a bit until it started going static in my fingers and I had to stop. I bounced on the bed a few times, but it wasn’t fun with nobody there, and the creaking of the springs echoed around the room, so I flopped down and lay in a heap of duvet. My phone was hidden in a little coil of the smoky quilt and I picked it up and checked the time. Three thirty. Still two hours before I could go to Lilah’s because she was at work, and nothing left to do.

I hadn’t wanted to go to Alice’s party all that much. I didn’t even like her really. She was always shouting and burping and talking about sex or shitting. She made me feel or seem shy, which I wasn’t. Always wearing leggings and tops that were too short, so that all you could look at was her crotch, which was perhaps the point. She wore her hair in a tight bun on the top of her head, held up with chopsticks, which made her face look huge. I could never say these things out loud because she was a good friend to Fitz and he loved her. She wanted to fill Hannah’s spot, to support him and care for him when he had suddenly had to become so many things to so many people. And, really, I wanted to be everything to him. And she was in the way.

I’d sat up and fiddled around in the duvet some more until I found the packet of tobacco and papers. Then I sat on the edge of the mattress and rolled a cigarette in my lap. Alice threw parties all the time, like she was Father Christmas or Hugh Hefner, so this one wasn’t exactly special. But with the quiet house and all the time to wait, I felt full of a weird curling anticipation and baby butterflies started circling in my belly.

I had sat out on the front step to smoke the cigarette. The concrete was cold on my feet, and rain was slowly colouring the steps dark. It was beautiful rain, the soft misty kind that hangs in the air and sits in your hair in tiny diamonds. I’d looked up at the pavement but there was nobody there, just the occasional swish-splash of a car driving past on the other side of the road. They only ever drove past on that side of the road, out of the city, and never on the other, never on the way in. Sometimes it seemed like the city must be getting empty, all the people leaving and nobody coming to take their place.

I wondered what Fitz was up to at work. He’d be making up set-lists, probably, bent over an order pad on the bar with a pencil in his hand and his hair falling in his eyes. Filling up the big glass jar of pistachios, green in their pink shells, or the olives, all glossy and black, chunks of garlic and chilli floating in the oil. Stacking the crisps on their shelf, checking there was enough of each bright colour, crackling the foil bags closer together to fit more of them in. Cleaning the pumps for the soft drinks, sticky with sugar and bubbly in the drip tray. Another car drove past up on the street out of sight, leaving a little trail of faint music as it went.

My cigarette had gone out in the damp fuzz of the rain, so I lit it and lay back, head inside on all the post, wiry doormat tickling my back and legs stretched out in the wet. Smoke drifted upwards and I looked up at the ceiling with a pizza flyer slippery under my head. That day there were no patterns or shapes to be made, just miles of meringue stretched from corner to corner.

The cigarette ran out again after a while, and I stood up and wandered into the lounge. I was shivering: it got cold in the flat when it rained, damp patches on the wall seeping through silently. I went over to Quin’s rail and pulled out one of his millions of blazers, a sailor’s one with white piping and braid and stripes on the shoulders. It was too big for me so I rolled up the sleeves and snuggled into it. My favourite blazer was missing; a red velvet one, which was soft like a hug when you put it on. Quin would have been wearing it; it was his favourite too. It was still cold, so I crouched on Quinnie’s sleeping bag and pulled his duvet round me. It smelt like him, of posh cigarettes and hair oil and just a tiny bit sweaty. There was a DVD case on the arm of the sofa with a bit of a line left on it, so I dabbed some and waited and waited for a high.

Time crawled by, until at last I could escape the emptiness. I left early and walked slowly to cheat it. Delilah’s flat was in a big old building with pretty windows and tall steps leading up to the front door. Every time I climbed them I felt pangs of jealousy. Lilah always told me that from the inside the windows were draughty and there were mice in the basement where the bins went, but as outsiders we can see things only as they seem. Envy was a feeling I collected as a diehard habit so truths like these often fell around me unheard. I pressed the buzzer and shifted the bag with the little bottle of vodka Fitz had bought me from one hand to the other. Molly, Delilah’s flatmate, answered, a blue paisley apron tied around her waist and a pan in one hand, a spoon in the other.

‘Hey, Saf! Come in, come in. You look gorgeous!’

I liked Molly. She was clever and pretty, with round pink cheeks, and she always had nice things to say to everybody. ‘Lilah’s in her room,’ she said, stirring the pot. ‘You want some bolognese?’

I shook my head, touched my stomach. ‘No, thanks, I just ate. Smells amazing.’

She smiled and went back into the kitchen, trailing hot tomato-garlic-wine scent behind her. I walked down the hall, looking at the framed photos on the bright white walls as I went. Lilah’s door was half open, music playing out, so I knocked and opened it at the same time. She was crouched in front of her mirror, straightening her hair and spraying each strand wildly as she went.

‘Hey, gorge,’ she said. ‘How’s it going?’

‘Good,’ I said, sitting down on the end of the bed and taking the bottle out of the bag. ‘How you doing?’ And before she could answer, I added, ‘Glasses?’

We’d sat for a while like that, me with my back against the wall and my legs stretched out on the satin duvet, Lilah kneeling by the mirror, preening and powdering and straightening and shining. She had started seeing a man at work, a client, and she didn’t want her boss to find out.

‘He’s so beautiful, Saf,’ she gushed, her gold eyes widening, her own beauty reflected back in the mirror.

‘I’m happy for you,’ I said, and I was, the vodka warming my heart and making the room pink in the lamplight. I racked up two lines on the cover of a hardback book, but as she turned to look in her huge toolbox of make-up, I snorted one and quickly racked up another.

‘Here,’ I said, as she turned back round. ‘Let’s celebrate.’

I held out the book and the note and she grinned, ‘Little fairy with your pixie dust.’ She scooted forward and knelt at my knees to do the line. I watched the tiny particles zip up her nose as her hair swooshed across the cover. She handed back the note and squeezed my boot. ‘Thanks, baby.’ She went back to the mirror, turning up the music as she passed. She started to sing, humming the beat aloud in her beautiful sparkly voice.

The thing with Lilah was that she started off each night like this. Full of happy, fun and glossy pretty. I’d look at her and feel so ordinary sat on the sides. She was shiny and new and I was growing-out roots and scuffed boots. She looked like the kind of person anything could happen to, like in fairytales and rubbish films, like she might drop her purse in the street and a prince or a footballer would bend to pick it up and fall in love with her. But as the night went on she’d get bored. She’d look around the room and she wouldn’t see anybody she liked or wanted to talk to and she wouldn’t know the music and she’d feel out of place. And her glossy would look too much, too bright in the dark loveliness of the night. And she’d sulk and start to whine, and she’d take her shoes off because her feet hurt, and she’d pull her hair back because it was too hot, and it made me realise that even beautiful people are only beautiful in their own place. Fitz thought that Lilah was a bit up herself, but I knew that she cried herself to sleep sometimes. I knew that she hated her job and I knew that she could never tell her parents about the abortion she had had or the married men she slept with and so I found a bit of her to love.

We did the lines and then we stood up and straightened ourselves out and then we left. Molly was pouring bolognese onto two perfect nests of spaghetti as we passed. There was a man’s shoe poking out from the kitchen table, but the door hid the leg and the body and the face. ‘Who is it?’ I asked Lilah, as we walked down the street, waiting to feel cold through the vodka but staying cosy in its warmth. She shrugged. ‘James, I guess. Someone boring like that.’ To Lilah, anyone without beauty or wealth was boring. It made me cross with her but it also made me feel relieved, because I knew that she couldn’t see the real wonder of Fitz and so he was safely mine.

The streetlights had been starting to come on as the sky turned darker grey, little globes of orange glowing along the long street. I took poppers from my pocket and offered them to Lilah. She shook her head. ‘God, no. What are you – sixteen? You’ll be sick …’ I laughed and put them to my nose anyway. The rest of the road rushed by in a warm lurch, lights brighter and cheeks warm, Lilah chattering away about everything and nothing.

I could feel the bass throbbing through the pavement as we walked up the drive, beating up through my feet and into my heart, leaving me short of breath and anxiously happy. The door was open and we stepped through into the dark. All of the light bulbs had been swapped for the coloured ones you could get in the pound shop, red in the hall. The walls had been covered with giant sheets of plain white paper, which people were already scrawling messages across.

We headed naturally for the kitchen, the place where everybody begins and ends a party. It was bustling busy, people perching on worktops and crowded around talking and reaching for things and filling glasses. The light bulb in the kitchen was green, everything and everybody suddenly seeming as if they were under water. I was already high and happy and didn’t want anything bringing me down, so I floated through without stopping, smiling at people and feeling the music rolling around my head. Alice was at the far end of the kitchen table, crotch glowing in the green light, and she jumped up excitedly and pulled me into her arms, showing me off to the rest of the table, like I was her pet, and then slipped a pill into my hand and danced off.

When we had gone into the lounge the light was dark blue, and people were dancing in a little clot in front of the decks. We danced in the blue dark for a while and I could feel my eyes starting to roll back behind my lids so I took Lilah’s hand and we sat down on the sofa. She was drinking wine slowly from the bottle, watching nobody in particular, and she ran her long fingers through my hair sending shivers over my rushing skin, tight and tiny pearls. My face and my mouth were dry and hot. The beat was pounding in my ears and I couldn’t breathe, like the darkest blue was shrinking in on me and the beat was growing and growing until it would crash down and cover me like a wave. Around me people were changing, shimmering gold glasses appearing over eyes and disappearing again, strange masks looming out of dark corners, faces melting into screams. I closed my eyes but the darkness sent me spinning. I stood, and the carpet lurched underneath me as I hurried out into the angry red of the hall and then into the toilet. I had to peel away a corner of white paper to get into it, and when I shut the door behind me, I could hear squeaky pens scribbling and scrawling messages on the inside of my skull.

The light was a normal greenish yellow in there, and I thought somewhere far inside my head that Alice must have run out of colours. I looked at my face in the mirror. My eyes were black and my skin was greenish yellow too, disappearing into the reflection of the walls and the door. My hair had come loose from its knot and was sticking to my scalp and cheeks like straw, falling limply down on my shoulders, and I pushed it and pulled it, disgusted. The bass pulsed through the door and in my veins, and as I pulled and tugged faster and faster at my hair and face my image blurred in the glass and the light seemed to shiver in its socket. I scraped my hair back and tied it with the band I kept round my wrist, but it was no good. I looked on the shelves and I found a tiny pair of nail scissors and I got hold of the ponytail between my fingers and hacked clean through it, the soft sound of the scissors snipping echoing around me in the pale light. Bleached clumps of fluffy hair fell into the sink like feathers. The sober me was stirring in the back of my head, panicking and fluttering anxiously, but I ignored her, shoved her back down. I left the hair feathers in the sink and pulled the band out so that my hair splayed around me, rough and uneven, and looked at my face for a long time until it stopped being my own and then I went back into the party. I went upstairs where the light was pink, and silvery strains of techno were spilling out and I did not look back.

I sat at my desk, still pulling at the new short chunks of my hair, the sketchbooks lying forgotten around me. I wondered, for the first time since I’d remembered cutting it, what it looked like but I didn’t get up to check. I sat, and I waited for Fitz to wake up.