По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

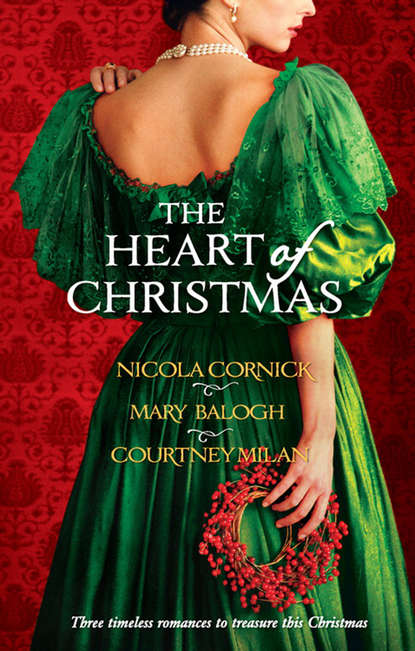

The Heart Of Christmas: A Handful Of Gold / The Season for Suitors / This Wicked Gift

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Come, Henry,” Mrs. Moffatt had said, “we will put the children to bed first. Perhaps I can see you in here for a few minutes afterward, Mrs. Simpkins.”

Mrs. Simpkins had been looking a delicate shade of green.

That was when Blanche had spoken up.

“You certainly will not manage alone,” she had assured the guest. “It will be quite enough for you to endure the pain of labor. You will leave the rest to us, Mrs. Moffatt. Sir,” she said, addressing the clergyman, “perhaps you can put the children to bed yourself tonight? Boys, give your mama a kiss. Doubtless there will be more than one wonderful surprise awaiting you in the morning. The sooner you fall asleep, the sooner you will find out what. Mrs. Lyons, will you see that a large pot of water is heated and kept ready? Mrs. Simpkins, will you gather together as many clean cloths as you can find? Debbie—”

“Ee, Blanche,” Debbie had protested, “no, love.”

“I am going to need you,” Blanche had said with a smile. “Merely to wield a cool, damp cloth to wipe Mrs. Moffatt’s face when she gets very hot, as she will. You can do that, can you not? I will be there to do everything else.”

Everything else. Like delivering the baby. Julian had stared, fascinated, at his opera dancer.

“Have you done this before, Blanche?” he had asked.

“Of course,” she had said briskly. “At the rectory—ah. I used to accompany the rector’s wife on occasion. I know exactly what to do. No one need fear.”

They had all been gazing at her, Julian remembered now. They had all hung on her every word, her every command. They had leaned on her strength and her confidence in a collective body.

Who the hell was she? What had a blacksmith’s daughter been doing hanging around a rectory so much? Apart from learning to play the spinet without music, that was. And apart from delivering babies.

Everyone had run to do her bidding. Soon only the three men—the three useless ones—had been left in the sitting room to fight terror and nausea and fits of the vapors.

The door opened. Three pale, terrified faces turned toward it.

Debbie was flushed and untidy and swathed in an apron made for a giant. One hank of blond hair hung to her shoulder and looked damp with perspiration. She was beaming and looking very pretty indeed.

“It is all over, sir,” she announced, addressing herself to the Reverend Moffatt. “You have a new…baby. I am not to say what. Your wife is ready and waiting for you.”

The new father stood very still for a few moments and then strode from the room without a word.

“Bertie.” Debbie turned tear-filled eyes toward him. “You should have been there, love. It came out all of a rush into Blanche’s hands, the dearest little slippery thing, all cross and crying and—and human. Ee, Bertie, love.” She cast herself into his arms and bawled noisily.

Bertie made soothing noises and raised his eyebrows at Julian. “I was never more relieved in my life,” he said. “But I am quite thankful I was not there, Deb. We had better get you to bed. You are not needed any longer?”

“Blanche told me I could go to bed,” Debbie said. “She will finish off all that needs doing. No midwife could have done better. She talked quietly the whole time to calm my jitters and Mrs. Simpkins’s. Mrs. Moffatt didn’t have the jitters. She just kept saying she was sorry to keep us up, the daft woman. I have never felt so—so honored, Bertie, love. Me, Debbie Markle, just a simple, honest whore to be allowed to see that.”

“Come on, Deb.” Bertie tucked her into the crook of his arm and bore her off to bed.

Julian followed them up a few minutes later. He had no idea what time it was. Some unholy hour of the morning, he supposed. He did not carry a candle up with him and no one had lit the branch in his room. Someone from belowstairs had been kept working late, though. There was a freshly made-up fire burning in the hearth. He went to stand at the window and looked out.

The snow had stopped falling, he saw, and the sky had cleared off. He looked upward and saw in that single glance that he had been wrong. It was not an unholy hour of the morning at all.

He was still standing there several minutes later when the door of the bedchamber opened. He turned his head to look over his shoulder.

She looked as Debbie had looked but worse. She was bedraggled, weary and beautiful.

“You should not have waited up,” she said.

“Come.” He beckoned to her.

She came and slumped tiredly against him when he wrapped an arm about her. She sighed deeply.

“Look.” He pointed.

She did not say anything for a long while. Neither did he. Words were unnecessary. The Christmas star beamed down at them, symbol of hope, a sign for all who sought wisdom and the meaning of their lives. He was not sure what either of them had learned about Christmas this year, but there was something. It was beyond words at the moment and even beyond coherent thought. But something had been learned. Something had been gained.

“It is Christmas,” she said softly at last. Her words held a wealth of meaning beyond themselves.

“Yes,” he said, turning his face and kissing the untidy titian hair on top of her head. “Yes, it is Christmas. Did they have their daughter?”

“Oh yes,” she said. “I have never seen two people so happy, my lord. On Christmas morning. Could there be a more precious gift?”

“I doubt it,” he said, closing his eyes briefly.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: