По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

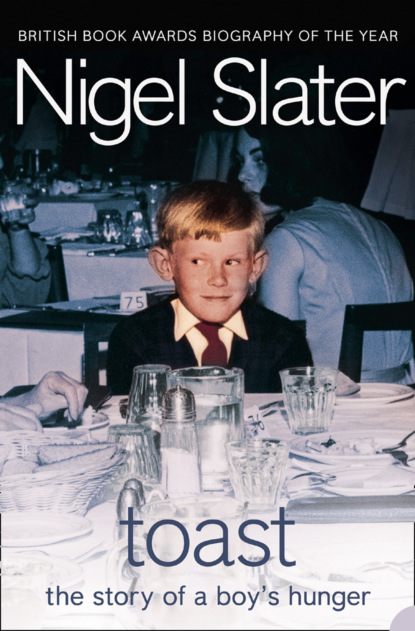

Toast: The Story of a Boy's Hunger

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Irish Stew (#litres_trial_promo)

Black Forest Gâteau (#litres_trial_promo)

Seafood Cocktail (#litres_trial_promo)

La Steak Diane (#litres_trial_promo)

Cold Roast Beef (#litres_trial_promo)

The Wimpy Bar (#litres_trial_promo)

Pommes Dauphinoise (#litres_trial_promo)

The Bistro (#litres_trial_promo)

Toast 3 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgement (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Nigel Slater (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Toast 1 (#ulink_1ff447e4-0fa5-5815-b9f6-c1bc0d92eb7d)

My mother is scraping a piece of burned toast out of the kitchen window, a crease of annoyance across her forehead. This is not an occasional occurrence, a once-in-a-while hiccup in a busy mother’s day. My mother burns the toast as surely as the sun rises each morning. In fact, I doubt if she has ever made a round of toast in her life that failed to fill the kitchen with plumes of throat-catching smoke. I am nine now and have never seen butter without black bits in it.

It is impossible not to love someone who makes toast for you. People’s failings, even major ones such as when they make you wear short trousers to school, fall into insignificance as your teeth break through the rough, toasted crust and sink into the doughy cushion of white bread underneath. Once the warm, salty butter has hit your tongue, you are smitten. Putty in their hands.

Christmas Cake (#ulink_e70de9ad-fd50-53e4-b379-cb725022ae24)

Mum never was much of a cook. Meals arrived on the table as much by happy accident as by domestic science. She was a chops-and-peas sort of a cook, occasionally going so far as to make a rice pudding, exasperated by the highs and lows of a temperamental cream-and-black Aga and a finicky little son. She found it all a bit of an ordeal, and wished she could have left the cooking, like the washing, ironing and dusting, to Mrs P., her ‘woman what does’.

Once a year there were Christmas puddings and cakes to be made. They were made with neither love nor joy. They simply had to be done. ‘I suppose I had better DO THE CAKE,’ she would sigh. The food mixer – she was not the sort of woman to use her hands – was an ancient, heavy Kenwood that lived in a deep, secret hole in the kitchen work surface. My father had, in a rare moment of do-it-yourselfery, fitted a heavy industrial spring under the mixer so that when you lifted the lid to the cupboard the mixer slowly rose like a corpse from a coffin. All of which was slightly too much for my mother, my father’s quaint Heath Robinson craftsmanship taking her by surprise every year, the huge mixer bouncing up like a jack-in-the-box and making her clap her hands to her chest. ‘Oh heck!’ she would gasp. It was the nearest my mother ever got to swearing.

She never quite got the hang of the mixer. I can picture her now, desperately trying to harness her wayward Kenwood, bits of cake mixture flying out of the bowl like something from an I Love Lucy sketch. The cake recipe was written in green biro on a piece of blue Basildon Bond and was kept, crisply folded into four, in the spineless AgaCookbook that lived for the rest of the year in the bowl of the mixer. The awkward, though ingenious, mixer cupboard was impossible to clean properly, and in among the layers of flour and icing sugar lived tiny black flour weevils. I was the only one who could see them darting around. None of which, I suppose, mattered if you were making Christmas pudding, with its gritty currants and hours of boiling. But this was cake.

Cooks know to butter and line the cake tins before they start the creaming and beating. My mother would remember just before she put the final spoonful of brandy into the cake mixture, then take half an hour to find them. They always turned up in a drawer, rusty and full of fluff. Then there was the annual scrabble to find the brown paper, the scissors, the string. However much she hated making the cake we both loved the sound of the raw cake mixture falling into the tin. ‘Shhh, listen to the cake mixture,’ she would say, and the two of us would listen to the slow plop of the dollops of fruit and butter and sugar falling into the paper-lined cake tin. The kitchen would be warmer than usual and my mother would have that I’ve-just-baked-a-cake glow. ‘Oh, put the gram on, will you, dear? Put some carols on,’ she would say as she put the cake in the top oven of the Aga. Carols or not, it always sank in the middle. The embarrassing hollow, sometimes as deep as your fist, having to be filled in with marzipan.

Forget scented candles and freshly brewed coffee. Every home should smell of baking Christmas cake. That, and warm freshly ironed tea towels hanging on the rail in front of the Aga. It was a pity we had Auntie Fanny living with us. Her incontinence could take the edge off the smell of a chicken curry, let alone a baking cake. No matter how many mince pies were being made, or pine logs burning in the grate, or how many orange-and-clove pomanders my mother had made, there was always the faintest whiff of Auntie Fanny.

Warm sweet fruit, a cake in the oven, woodsmoke, warm ironing, hot retriever curled up by the Aga, mince pies, Mum’s 4711. Every child’s Christmas memories should smell like that. Mine did. It is a pity that there was always a passing breeze of ammonia.

Cake holds a family together. I really believed it did. My father was a different man when there was cake in the house. Warm. The sort of man I wanted to hug rather than shy away from. If he had a plate of cake in his hand I knew it would be all right to climb up on to his lap. There was something about the way my mother put a cake on the table that made me feel that all was well. Safe. Secure. Unshakeable. Even when she got to the point where she carried her Ventolin inhaler in her left hand all the time. Unshakeable. Even when she and my father used to go for long walks, walking ahead of me and talking in hushed tones and he would come back with tears in his eyes.

When I was eight my mother’s annual attempt at icing the family Christmas cake was handed over to me. ‘I’ve had enough of this lark, dear, you’re old enough now.’ She had started to sit down a lot. I made only marginally less of a mess than she did, but at least I didn’t cover the table, the floor, the dog with icing sugar. To be honest, it was a relief to get it out of her hands. I followed the Slater house style of snowy peaks brought up with the flat of a knife and a red ribbon. Even then I wasn’t one to rock the boat. The idea behind the wave effect of her icing was simply to hide the fact that her attempt at covering the cake in marzipan resembled nothing more than an unmade bed. Folds and lumps, creases and tears. A few patches stuck on with a bit of apricot jam.

I knew I could have probably have flat-iced a cake to perfection, but to have done so would have hurt her feelings. So waves it was. There was also a chipped Father Christmas, complete with a jagged lump of last year’s marzipan round his feet, and the dusty bristle tree with its snowy tips of icing. I drew the line at the fluffy yellow Easter chick.

Baking a cake for your family to share, the stirring of cherries, currants, raisins, peel and brandy, brown sugar, butter, eggs and flour, for me the ultimate symbol of a mother’s love for her husband and kids, was reduced to something that ‘simply has to be done’. Like cleaning the loo or polishing the shoes. My mother knew nothing of putting glycerine in with the sugar to keep the icing soft, so her rock-hard cake was always the butt of jokes for the entire Christmas. My father once set about it with a hammer and chisel from the shed. So the sad, yellowing cake sat round until about the end of February, the dog giving it the occasional lick as he passed, until it was thrown, much to everyone’s relief, on to the lawn for the birds.

Bread-and-Butter Pudding (#ulink_490e5e8f-9304-5d80-81bd-9c9523931c63)

My mother is buttering bread for England. The vigour with which she slathers soft yellow fat on to thinly sliced white pap is as near as she gets to the pleasure that is cooking for someone you love. Right now she has the bread knife in her hand and nothing can stop her. She always buys unwrapped, unsliced bread, a pale sandwich loaf without much of a crust, and slices it by hand.

My mother’s way of slicing and buttering has both an ease and an awkwardness about it. She has softened the butter on the back of the Aga so that it forms a smooth wave as the butter knife is drawn across it. She spreads the butter on to the cut side of the loaf, then picks up the bread knife and takes off the buttered slice. She puts down the bread knife, picks up the butter knife and again butters the freshly cut side of the loaf. She carries on like this till she has used three-quarters of the loaf. The rest she will use in the morning, for toast.

The strange thing is that none of us really eats much bread and butter. It’s like some ritual of good housekeeping that my mother has to go through. As if her grandmother’s dying words had been ‘always make sure they have enough bread and butter on the table’. No one ever sees what she does with all the slices we don’t eat.

I mention all the leftover bread and butter to Mrs Butler, a kind, gentle woman whose daughter is in my class at school and whose back garden has a pond with newts and goldfish, crowns of rhubarb and rows of potatoes. A house that smells of apple crumble. I visit her daughter Madeleine at lunchtime and we often walk back to school together. Mrs Butler lets me wait while Madeleine finishes her lunch.

‘Well, your mum could make bread-and-butter pudding, apple charlotte, eggy bread, or bread pudding,’ suggests Mrs Butler, ‘or she could turn them into toasted cheese sandwiches.’

I love bread-and-butter pudding. I love its layers of sweet, quivering custard, juicy raisins, and puffed, golden crust. I love the way it sings quietly in the oven; the way it wobbles on the spoon.

You can’t smell a hug. You can’t hear a cuddle. But if you could, I reckon it would smell and sound of warm bread-and-butter pudding.

Sherry Trifle (#ulink_9d1dea13-57db-56b7-ab85-196a7bdd3ebd)

My father wore old, rust-and-chocolate checked shirts and smelled of sweet briar tobacco and potting compost. A warm and twinkly-eyed man, the sort who would let his son snuggle up with him in an armchair and fall asleep in the folds of his shirt. ‘You’ll have to get off now, my leg’s gone to sleep,’ he would grumble, and turf me off on to the rug. He would pull silly faces at every opportunity, especially when there was a camera or other children around. Sometimes they would make me giggle, but other times, like when he pulled his monkey face, they scared me so much I used to get butterflies in my stomach.

His clothes were old and soft, which made me want to snuggle up to him even more. He hated wearing new. My father always wore old, heavy brogues and would don a tie even in his greenhouse. He read the Telegraph and Reader’s Digest. A crumpets-and-honey sort of a man with a tight little moustache. God, he had a temper though. Sometimes he would go off, ‘crack’, like a shotgun. Like when he once caught me going through my mother’s handbag, looking for barley sugars, or when my mother made a batch of twelve fairy cakes and I ate six in one go.

My father never went to church, but said his prayers nightly kneeling by his bed, his head resting in his hands. He rarely cursed, apart from calling people ‘silly buggers’. I remember he had a series of crushes on singers. First, it was Kathy Kirby, although he once said she was a ‘bit ritzy’, and then Petula Clark. Sometimes he would buy their records and play them on Sundays after I had listened to my one and only record – a scratched forty-five of Tommy Steele singing ‘Little White Bull’. The old man was inordinately fond of his collection of female vocals. You should have seen the tears the day Alma Cogan died.

The greenhouse was my father’s sanctuary. I was never sure whether it smelled of him or he smelled of it. In winter, before he went to bed, he would go out and light the old paraffin stove that kept his precious begonias and tomato plants alive. I remember the dark night the stove blew out and the frost got his begonias. He would spend hours down there. I once caught him in the greenhouse with his dick in his hand. He said he was just ‘going for a pee. It’s good for the plants.’ It was different, bigger than it looked in the bath and he seemed to be having a bit of a struggle getting it back into his trousers.

He had a bit of a thing about sherry trifle. That and his dreaded leftover turkey stew were the only two recipes he ever made. The turkey stew, a Boxing Day trauma for everyone concerned, varied from year to year, but the trifle had rules. He used ready-made Swiss rolls. The sort that come so tightly wrapped in cellophane you can never get them out without denting the sponge. They had to be filled with raspberry jam, never apricot because you couldn’t see the swirl of jam through the glass bowl the way you could with raspberry. There was much giggling over the sherry bottle. What is it about men and booze? They only cook twice a year but it always involves a bottle of something. Next, a tin of peaches with a little of their syrup. He was meticulous about soaking the sponge roll. First the sherry, then the syrup from the peaches tin. Then the jelly. To purists the idea of jelly in trifle is anathema. But to my father it was essential. If my father’s trifle was human it would be a clown. One of those with striped pants and a red nose. He would make bright yellow custard, Bird’s from a tin. This he smoothed over the jelly, taking an almost absurd amount of care not to let the custard run between the Swiss roll slices and the glass. A matter of honour no doubt.

Once it was cold, the custard was covered with whipped cream, glacé cherries and whole, blanched almonds. Never silver balls, which he thought common, or chocolate vermicelli, which he thought made it sickly. Just big fat almonds. He never toasted them, even though it would have made them taste better. In later years my stepmother was to suggest a sprinkling of multicoloured hundreds and thousands. She might as well have suggested changing his daily paper to the Mirror.

The entire Christmas stood or fell according to the noise the trifle made when the first massive, embossed spoon was lifted out. The resulting noise, a sort of squelch-fart, was like a message from God. A silent trifle was a bad omen. The louder the trifle parped, the better Christmas would be. Strangely, Dad’s sister felt the same way about jelly – making it stronger than usual just so it would make a noise that, even at her hundredth birthday tea, would make the old bird giggle.

You wouldn’t think a man who smoked sweet, scented tobacco, grew pink begonias and made softly-softly trifle could be scary. His tempers, his rages, his scoldings scared my mother, my brothers, the gardener, even the sweet milkman who occasionally got the order wrong. Once, when I had been caught not brushing my teeth before going to bed, his glare was so full of fire, his face so red and bloated, his hand raised so high that I pissed in my pyjamas, right there on the landing outside my bedroom. For all his soft shirts and cuddles and trifles I was absolutely terrified of him.

The Cookbook (#ulink_677fce6c-578e-50b3-b653-17b751589e52)

The bookcase doubled as a drinks cabinet. Or perhaps that should be the other way around. Three glass decanters with silver labels hanging around their necks boasted Brandy, Whisky and Port, though I had never known anything in them, not even at Christmas. Dad’s whisky came from a bottle, Dimple Haig, that he kept in a hidden cupboard at the back of the bookcase where he also kept his Canada Dry and a jar of maraschino cherries for when we all had snowballs at Christmas. The front of the drinks cabinet housed his entire collection of books.

The family’s somewhat diminutive library had leatherette binding and bore Reader’s Digest or The Folio Society on their spines. Most were in mint condition, and invariably ‘condensed’ or ‘abridged’. Six or so of the books were kept in the cupboard at the back, with the Dimple Haig and a bottle of advocaat; a collection of stories by Edgar Allan Poe, a dog-eared Raymond Chandler, a Philip Roth and a neat pile of National Geographics. There was also a copy of Marguerite Patten’s All Colour Cookbook.

It was a tight fit in between the wall and the back of the bookcase. Dad just opened the door and leaned in to get his whisky; it was more difficult for me to get round there, to wriggle into a position where I could squat in secret and turn the pages of the hidden books. I don’t know how Marguerite Patten would feel knowing that she was kept in the same cupboard as Portnoy’s Complaint, or that I would flip excitedly from one to the other. I hope my father never sells them. ‘For sale, one copy each of Marguerite Patten’s All Colour Cookery and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, first edition, d/w, slightly stained.’

‘I don’t know what you want to look at that for,’ said Mum once, coming home early and catching me gazing at a photograph of Gammon Steaks with Pineapple and Cherries. ‘It’s all very fancy, I can’t imagine who cooks like that.’ There was duck à l’orange and steak-and-kidney pudding, fish pie, beef Wellington and rock cakes, fruit flan and crème caramel. There was page after page of glorious photographs of stuffed eggs, sole with grapes and a crown roast of lamb with peas and baby carrots around the edge, parsley sprigs, radish roses, cucumber curls. Day after day I would squeeze round and pore over the recipes fantasising over Marguerite’s devilled kidneys and Spanish chicken, her prawn cocktail and sausage rolls. Just as I would spend quite a while fantasising over Portnoy’s way with liver.

The Lunch Box (#ulink_72587dcc-306f-5e01-ad50-95a628f4d65c)