По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

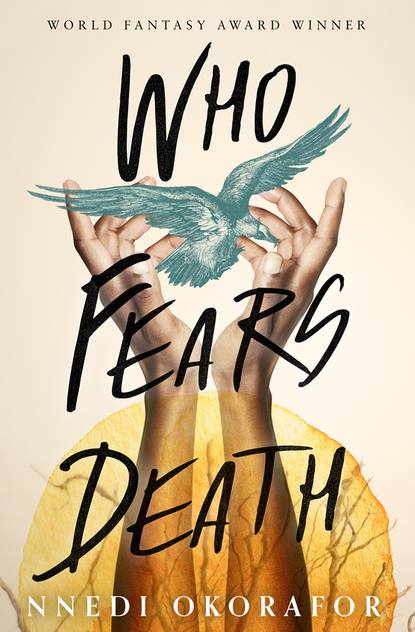

Who Fears Death

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It was like looking into a mirror when you’ve never seen your reflection. For the first time, I understood why people stopped, dropped things, and stared when they saw me. He was my skin tone, had my freckles, and his rough golden hair was shaved so close that it looked like a coat of sand. He might have been a little taller, maybe a few years older than me. Where my eyes were gold-brown like a desert cat’s, his were a gray like a coyote’s.

I instantly knew who he was, though I’d only seen him for a moment when I was in a disheveled state. Contrary to what Luyu told me, he’d been in Jwahir longer than the few days. He was the boy who saw me naked in the iroko tree. He’d told me to jump. It had been raining hard and he’d been holding a basket over his head but I knew it was him.

“You’re …”

“So are you,” he said.

“Yeah. I’ve never … I mean, I’ve heard of others.”

“I’ve seen others,” he said offhandedly.

“Where are you from?” we both asked at the same time.

We both said, “The West.” Then we nodded. All Ewu were from the West.

“Are you all right?” he asked.

“Eh?”

“You’re walking oddly,” he said. I felt my face grow hot. He smiled again and shook his head. “I shouldn’t be so bold.” He paused. “But trust me, they will always see us as evil. Even if you have yourself … cut.”

I frowned.

“Why would you have that done?” he asked. “You’re not from here.”

“But I live here,” I said, defensively.

“So?”

“Who are you?” I said, irritated.

“Your name is Onyesonwu Ubaid-Ogundimu. You’re the blacksmith’s daughter.”

I bit my lip, trying to remain irritated. But he’d referred to me as the blacksmith’s daughter, not stepdaughter, and I wanted to smile at this. He smirked. “And you’re the one who ends up naked in trees.”

“Who are you?” I asked again. How strange we must have looked standing there on the side of the road.

“Mwita,” he said.

“What’s your last name?”

“I have no last name,” he said, his voice growing cold.

“Oh … okay.” I looked at his clothing. He wore typical boy attire, faded blue pants and a green shirt. His sandals were worn but made of leather. He carried a satchel of old schoolbooks. “Well … where do you live?” I asked.

The coolness thawed from his voice. “Don’t worry about it.”

“How come you don’t come to school?”

“I’m in school,” he said. “A better one than yours.” He reached into his pocket and pulled out an envelope. “This is for your father. I was going to your home but you can take it to him.” It was a palm fiber envelope stamped with the insignia of the Osugbo, a lizard in midstride. Each of its legs represented one of the elders.

“You live up the road past the ebony tree, right?” he asked, looking past me.

I nodded absentmindedly, still looking at the envelope.

“Okay,” he said. Then he left. I stood there watching him walk away, barely aware of the fact that the throbbing between my legs had grown worse.

Chapter 6 (#ulink_b30b3343-b82e-5f44-916e-30b54c238777)

Eshu (#ulink_b30b3343-b82e-5f44-916e-30b54c238777)

AFTER THAT DAY, it seemed I saw Mwita everywhere. He often came to our house with messages. And a few times I ran into him on his way to Papa’s shop.

“How come you didn’t tell me about him before?” I asked my parents one night during dinner. Papa was shoveling spiced rice into his mouth with his right hand. He sat back, chewing, his right hand resting over his food. My mother put another piece of goat meat on his plate.

“I thought you knew,” he said at the same time that my mother said, “I didn’t want to upset you.” My parents knew so much back then. They should have also known that they couldn’t shelter me forever. What was coming would come.

Mwita and I talked whenever we saw each other. Briefly. He was always in a hurry. “Where’re you going?” I asked after he delivered yet another envelope from the elders to Papa. Papa was making a great table for the House of the Osugbo, and the engraved symbols on it had to be perfect. The envelope Mwita brought contained more drawings of the symbols.

“Somewhere else,” Mwita said, smirking.

“Why’re you always hurrying?” I said. “Come on. Just one thing?”

He turned to leave and then he turned back. “All right,” he said. We sat on the steps to the house. After a minute he said, “If you spend enough time in the desert, you will hear it speak.”

“Of course,” I said. “It speaks loudest in wind.”

“Right,” Mwita said. “Butterflies understand the desert well. That’s why they move this way and that. They’re always Holding Conversation with the land. They talk as much as they listen. It’s in the desert’s language that you call the butterflies.”

He lifted his chin, took a deep breath and breathed out. I knew the song. The desert sang it when all was well. In our nomad days, my mother and I would catch scarab beetles slowly flying by on days when the desert sang this song. Remove the hard shells and wings, dry the flesh in the sun, add spices—delicious. Mwita’s song brought three butterflies—a tiny white one and two big black and yellow ones.

“Let me try,” I said, excitedly. I thought about my first home. Then I opened my mouth and sang the desert’s song of peace. I drew two hummingbirds who zipped around our heads before flying off. Mwita leaned away from me, shocked.

“You sing like … your voice is lovely,” he said.

I looked away, pressing my lips together. My voice was a gift from an evil man.

“Some more,” he said. “Sing some more.”

I sang him a song I’d made up when I was happy and free and five years old. My memory of those times was fuzzy, but I clearly remembered the songs I sang.

It was like that each time with Mwita. He’d teach me a bit of simple sorcery and then be shocked by the ease with which I picked it up. He was the third to see it in me (my mother and Papa being the first and second), probably because he had it in him too. I wondered where he learned what he knew. Who were his parents? Where did he live? Mwita was so mysterious … and very handsome.

Binta, Diti, and Luyu first met him at school. He was waiting for me in the yard, something he’d never done. He wasn’t surprised to see me come out of school with Binta, Diti, and Luyu. I’d told him much about them. Everyone was staring. I’m sure many stories were told that day about Mwita and me.

“Good afternoon,” he said, politely nodding.

Luyu was grinning too widely.