По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

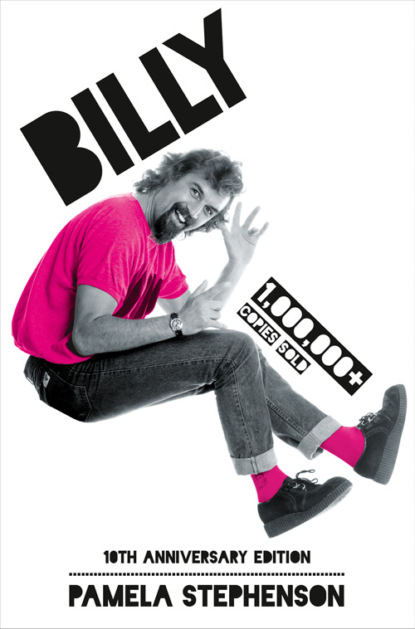

Billy Connolly

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Charlie was a hoot. Out of his grinning, ‘smart-ass’ mouth came some great sassy American expressions, such as ‘Hey buster, how’d you like your eye done – black or blue?’ He would sit in the tenement window three floors up with one leg dangling. ‘Hey guys, you wanna drink?’ He would squirt them with a water pistol.

Even Margaret and Mona loosened up when Charlie was around, and they all went to the variety theatre together. Billy used to tell people they were all going to America to live on his Uncle Charlie’s ranch and they were going to get a car each.

There is a hefty, red sandstone Victorian apartment building in Stewartville Street that was originally St Peter’s School for Boys. The sunken car park was once a playground full of youngsters careering pell-mell from corner to corner and Billy loved to sit with his legs dangling through the railings, watching them with envy. Sometimes he even caught some of the older students hurrying out at lunchtime, heading for a nearby shop where they could buy a single cigarette for a penny, and a slice of raw turnip for a half-penny. Billy thought they were gods. He simply could not wait to be a schoolboy, and imagined himself smoking cigarettes, eating turnips, and wearing fight-smart, studded boots that made sparks in the street. He soon got part of his wish, for the aunts decreed that it was time for both him and Florence to attend school.

Very young Catholic boys attended St Peter’s Girls’ School, and then moved on to the boys’ school once they turned six. Billy’s first teacher at kindergarten was Miss O’Halloran and, at five years old, he doted on her. In her classroom it was all Plasticine and lacing wool through holes in cards. Miss O’Halloran was amazed he could already write (Florence had taught him) and Billy was paraded round the school as a great example. He even went to Florence’s class where to everyone’s amazement he formed the letter ‘J’ on the board. But, despite his early star pupil status, Billy was terrified of the nuns, and was especially wary of Sister Philomena who had pictures of hell on her wall that looked like travel brochures. Billy assumed she’d been there.

When he moved up to the boys’ school at six years old, there was a harshness he’d not experienced in kindergarten. In the main hallway there was a massive crucifix, a bleeding, life-sized Christ that thoroughly spooked him. Billy had not yet been fully indoctrinated into the faith, but once he was at the boys’ school that occurred as swiftly and as subtly as a fishhook in the nostril: on his first day at the new school his teacher Miss Wilson informed him that Jesus was dead and that he, Billy, was personally responsible. And that wasn’t the only bad news. From now on, he was to be addressed as ‘Connolly’ instead of ‘Billy’.

Things were changing at home as well. William, who was probably traumatized by his wartime experiences, seemed remote and gruff to his children. He was generous as far as his means would allow and Florence and Billy looked forward to Fridays when he would come home from his job in a machine parts factory, bearing comic books, Eagle for Billy and Girl for Florence. But, although he could be quite flush with a full pay packet, he generally proved to be an inconsistent and absent parent.

As time went on and the children became less of a novelty, the aunts began to fully comprehend the sacrifices they would have to make in order to bring them up. It gradually dawned on Mona and Margaret that their single lives were now over, for dating and marriage would henceforth be difficult at best. Consequently, they began to sour, and the atmosphere at home changed drastically for the worse. There was a hymn at the time, a favourite of Billy’s. It was called ‘Star of the Sea’:

‘Dark night has come down on this heavenly world

And the banners of darkness are slowly unfurled.

Dark night has come down, dear mother and we

Look out for thy shining, sweet star of the sea.

Star of the sea, sweet star of the sea

Look out for thy shining, sweet star of the sea.’

And that’s what he felt had happened. ‘This is definitely different,’ he thought to himself at six years old. ‘God’s dead, my first name’s gone, and the whole fucking thing’s my fault.’

2 ‘He’s got candles in his loaf!’ (#ulink_bae1fb2c-c505-57ab-9a02-6b877dceca63)

It is late fall in Philadelphia, 24 November 2000. An eclectic crowd is jammed into an arts-district theatre. Few people are still hugging their weatherproof outerwear, so under the seats are strewn woollen, nylon, or leather garments that have slid silently downwards as bodies began to relax and shake with hysteria.

Election time in the United States is a comedian’s gift of a social climate. ‘If you don’t make up your mind about your president pretty quick, the country’s going to revert to us British,’ threatens the shaggy, non-voting Glaswegian with the radio microphone, ‘and look at the choice you’ve got! Gore – what a big fucking Jessie he is … and George W. Bush – God almighty!’ A rant against politicians follows, and so do cheers and applause from this thoroughly fed-up bunch of voters. ‘I’ve been saying all along: don’t vote! It only encourages the bastards!’

The harangue eventually switches to introspection, and soon the theme is the march of time, probably inspired by the fact that this is the night of his fifty-eighth birthday. He bashfully announces this to the throng, which prompts a rowdy bunch on the right-hand side to instigate a swell, until the entire audience is singing happy birthday to Billy.

‘Shut the fuck up!’ he wails at them. ‘Behave yourselves!’ Every single detail of his highly embarrassing prostate exam has just been shared with all these strangers, yet the intimacy of a birthday celebration is making him very uncomfortable.

Later on, in the dressing room, there is a tiny cake from his promoter. Billy has just moaned to his audience that his birthday cake now holds nearly three boxes of candles, but the promoter’s sponge-and-frosting round has only four snuff-resistant flames dancing above a chocolate greeting. As always, Billy is shattered, sweaty, and still in a fragile trance from the show. I shower him with kisses and praise for a brilliant performance, but he slumps glumly in the couch, staring fixedly at the cake.

He is transported to the circus in Glasgow more than fifty years ago. Among the most terrifying characters from his six-year-old experience were, ironically, clowns, and one of these scary, painted monsters is riding a unicycle while balancing a birthday cake on his shoulder. Unaccustomed to being celebrated for being alive, wee Billy has never seen a birthday cake before that moment. ‘Look!’ he cries, to the amusement of his sister and aunts. ‘He’s got candles in his loaf!’

Nowadays, I like to order an extravagant loaf of breadshaped chocolate birthday cake with candles for Billy, which he always hugely enjoys, but back then, at St Peter’s School for Boys, special treats were unheard of. Absolutely everything seemed threatening. A boy was to march in file and remember his arithmetic tables or else. The punishment for noncompliance involved several excruciatingly painful whacks with a tawse, an instrument of torture made in Lochgelly in Fife. It was a leather strap about a quarter of an inch thick, with one pointed end, and three tails at the other. The teacher’s individual preference dictated which end Billy and the other boys would receive. Most liked to hold the three tails and wallop the culprit with the thick end. When a boy was considered a candidate for receiving this abuse, he was forced to hold one hand underneath the other, with arms outstretched. The tawse was supposed to find its target somewhere on the hand, but Billy noticed that teachers seemed to take great delight in hitting that very tender bit on his wrist, and making a nasty weal. Most of the boys, however, were quite keen on having battle scars.

Rosie McDonald, the worst teacher of the bunch, whom Billy describes as ‘the sadist’, would make her victim stand with hands, palms up, about an inch above her desk. When she wielded her tawse, the back of his hands would come crashing down painfully on top of pencils she’d placed underneath. That was her special treat in winter, when the chilly air made even youthful joints stiffer and more sensitive. Among her pupils, Rosie had favourites, but Billy was definitely not one of them. Scholastically, he did not seem to be grasping things nor keeping up with his homework, so Rosie assumed that he was lazy and stupid and punished him viciously.

Everyone who knows Billy today is aware of his considerable, albeit unusual, intelligence. However, he does not process information the same way that many others do. Psychologists currently ascribe diagnoses such as ‘Attention Deficit Disorder’ or ‘Learning Disability’ to such a way of thinking and, in the more enlightened educational environments, there is understanding and help for such children. In addition to having a learning difference, however, Billy is and was a poet and a dreamer, as well as a person suffering from past and present trauma, and these factors all conspired to make concentration and left-brain activity extremely challenging for him. Rosie thrashed him for many things that were unavoidable, considering his organic make-up: for looking out the window, for breaking a pencil, for scruffy writing or untidy paper, or for looking away when she was talking. He used to stand outside her classroom because he was too scared to go in. Eventually, someone would either push or pull him inside, and Rosie would start on him for his tardiness. ‘Well look who’s here! Well, well, well! Slept in, did you? Well, maybe we should wake you up.’

Once she got her favourites, James Boyd and Peter Langan, to run him up and down the classroom holding an arm each. The most humiliating part for Billy was seeing his play-piece, a little butter sandwich that he carried up his jersey, come jumping out in the process, and being trampled on by all.

Rosie was always furious and suspicious with the class. When she strapped people, she did it so violently that she invariably back-heeled her leg and kicked her desk at the same time, so eventually it featured a massive crater of cracked wood. Other teachers would pop into her classroom from time to time for various reasons and Billy would be amazed to see them occasionally having a laugh with her. They think she’s normal.’ he would marvel, ‘a normal human being. Probably if you asked them what she was like, they’d even say she was nice, this horrible, terrifying beast.’

Billy still believes the bravest thing in his whole life was the day he decided to stop doing homework. Just never did it any more. The first morning after this epiphany, he awaited the inevitable with a new-found, insolent calm.

‘Have you done your homework?’ demanded Rosie.

‘No.’

‘Out here.’

Thwack! Thwack! Thwack!

‘Sit down.’

The next day it was the same thing, and the next, and the next. Reflecting on it now, Billy recognizes that he probably wouldn’t have been able to do Rosie’s maths homework anyway, and was too intimidated to ask for help. In common with most people who have a learning disability, he is afraid of many tasks and procrastinates as a way of trying to deal with that fear.

Rosie was not the only tyrant in Billy’s six-year-old life, for Mona had started taking her frustration out on Billy, and he was experiencing her, too, as a vicious bully. Mona was exactly like Rosie: suspicious, paranoid, and sadistic. She had started picking on him fairly soon after they had settled into Stewartville Street. At first it was verbal abuse. She called him a ‘lazy good-for-nothing’, pronounced that he would ‘come to nothing’, and that it was ‘a sad day’ when she met him.

She soon moved on to inflicting humiliation on Billy, her favourite method being grabbing him by the back of his neck and rubbing his soiled underpants in his face. She increased her repertoire to whacking his legs, hitting him with wet cloths, kicking him, and pounding him on the head with high-heeled shoes. She would usually wait until they were alone, then corner and thrash him four or five times a week for years on end.

Billy, however, had been in a few scraps in the school playground and had decided that a smack in the mouth wasn’t all that painful. The more experience he had of physical pain, the more he felt he could tolerate it. ‘What’s the worst she could do to me?’ he would ask himself. ‘She could descend on me and beat the shit out of me … but a couple of guys have done that to me already and it wasn’t that bad … I didn’t die or anything.’

In fact, the more physical, emotional and verbal abuse he received, the more he expected it, eventually believing what they were telling him: that he was useless and worthless and stupid, a fear he keeps in a dark place even today. As a comedian whose brilliance now emanates largely from his extraordinarily accurate observation of humanity, he has gloriously defied Mona’s favourite put-down: ‘Your powers of observation are nil.’ She was the only person Billy ever knew who said the word ‘nil’ when it wasn’t about a football result.

Florence was sometimes physically present when Mona mercilessly scorned and beat her brother. She would stand there frozen and helpless, immobilized by fear and horror. The mind, however, has a marvellous capacity to escape when the body can’t. Psychologists call it ‘dissociation’ and view it as a survival mechanism. Florence mentally flew to a far corner of the ceiling and watched the hideous abuse from ‘safety’. ‘I was there, but I wasn’t there,’ she explains now. ‘I was outside, looking in.’ It was very traumatic for her too, and very dangerous, for dissociation can leave an indelible mark on the psyche.

Billy, on the other hand, put his energy into trying to defend himself from Mona’s blows by shielding his face and body with his arms. His adrenaline would surge and, although he was no match for her, at least he managed to avoid getting broken teeth. He remembers the blood from his nose dripping onto his feet. Billy is a survivor: in common with many traumatized children, he adopted a pretty good coping strategy. If you ask him about it now, he says, ‘It sounds hellish, but it was quite bearable once you got your mind right. It doesn’t kill you.’ But his scars ran deeper than flesh wounds, especially those from the humiliating words that accompanied his beatings. Being too young to come up with a rational, adult explanation for it, he could only make sense of Mona’s sadistic treatment by fully accepting what she said, that he was indeed a sub-standard child. ‘I must deserve this,’ he decided.

Mona’s paranoia and suspiciousness were relentless, pathological and extremely alarming. An older boy at school gave Billy a small model boat that he had made in woodwork class.

‘Where did you get that?’ Mona asked him accusingly.

‘A big boy gave it to me.’

‘Don’t tell lies. Why would anyone give you a boat for nothing? Come on! Tell me! Where did you really get it?’

There was no other answer, so she pounded him until he bled.

Margaret wasn’t as manic a bully as Mona but she was on her side. She had been very beautiful when she was younger, a hair-dresser’s model at Eddy Graham’s. Eddy’s shop smelled of rotten eggs, and Billy always wondered how she could sit through such a terrible smell. Billy admired Margaret’s sense of style, but thought Mona looked an absolute mess most of the time. For a start, she never put her teeth in unless she went out. This wasn’t all that unusual, for at that time in Glasgow there was a fashion for having no teeth. When National Health false teeth became available, people of all ages thought it was an excellent idea to replace their existing teeth with those new, shiny, perfect ones. Some would actually have their teeth taken out for their twenty-first birthday, as a pragmatic choice, since they were eventually going to fall out anyway.

Whenever the auburn roots of Mona’s dyed blonde hair began to grow out, she would send Billy down to Boots to buy her peroxide.

‘A bottle of peroxide, please, twenty volumes.’

He would carry home the little brown bottle and be swept in by a vision in slippers, a pale cardigan and a skirt and apron. Hoping to catch some young man’s eye, Mona and Margaret both dolled themselves up whenever they ventured out. When nylons were in short supply, the sisters would get creative with Bisto, plastering the gravy all over their bare legs and wandering around the city stinking like a Sunday dinner.

On 8 May 1949, when Billy was six and a half, Mona mysteriously produced a baby son whom she named Michael. Her paramour was a local man who had no inclination to marry Mona; his identity remained a puzzle to his own son until adulthood. No one ever explained the situation to the growing Michael at all; as a matter of fact, he was presented to the world as a brother to Billy and Florence and nobody seemed to question it. In those postwar years, there were many similar situations and, curiously enough, the otherwise judgemental society seemed to tolerate it.

Today, having a famous ‘brother’ has hardly helped Michael to ward off speculation about his birth circumstances. At first he thoroughly resented those who drew attention to his situation. ‘But I’ve learned to just shrug it off,’ he says now, with questionable insistence. ‘Whatever people say about me, Billy or the family … I don’t care.’