По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

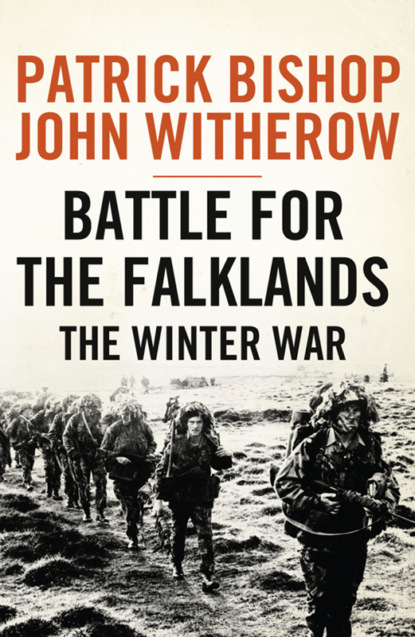

Battle for the Falklands: The Winter War

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It is extraordinary the extent to which people behave in a war in the way that the war films would have you believe. In the middle of the battle for Mount Tumbledown, John Witherow saw a young Guards lieutenant from the Blues and Royals wandering down the road from the fighting looking fiercely indignant. ‘The swine have gone and blown up my tank,’ he said. Earlier on, while wandering around in the darkness in the worst weather of the war looking for a trench, he came across a lone figure hunched against the wind, his cape flowing behind him like a cartoon character. ‘Who was that outside?’ he asked when we found some shelter. ‘Oh, that will be Lord Dalrymple,’ said a sergeant. ‘He’s always out there.’ On the day after the battle for Mount Longdon a pair of Harriers swooped along the side of Mount Kent on their way to a bombing raid on Port Stanley and as the troops cheered and shouted they switched on their vapour trails and climbed into the sky leaving a perfect victory ‘V’ in their wake.

People spoke in war comic clichés. They really did say, ‘We’re going to knock the Argies for six.’ A Marine lieutenant heading off on a night patrol to draw the enemy fire and locate their positions said: ‘Looks like we’re set for some good sport tonight.’ Perhaps because it had been so long since Britain had fought a conventional war a lot of the language and images were borrowed from American literature and films about the Vietnam war. ‘It’s just like Apocalypse Now,’ said a Marine in awe watching the tracer crackle over the side of Mount Harriet. Soldiers predicted that if the Argies were ‘zapped’ heavily enough they were bound to ‘bug out’.

The doctors and medical orderlies in the gloomy field dressing station at Ajax Bay and on board the hospital ship Uganda half consciously modelled themselves on the heroes of ‘MASH’ although the best words and expressions were their own. ‘Yomping’ was an almost onomatopoeiac term for trekking heavily-laden over difficult ground. It described the activity perfectly. No one knew where it came from, though exhaustive research by John Silverlight of the Observer seems to suggest it has its origins in the Norwegian skiing term for crossing an obstacle.

Significantly, there were two terms for acquiring pieces of equipment dishonestly. One was called ‘proffing’, the other ‘rassing’, derived from the naval shorthand for Replenishment At Sea. Looted items were known as ‘gizzits’, short for ‘give us it’. ‘Proffing’ was a way of life. One of us left a pair of ski gloves to dry out on top of a boiler in a settlement farmhouse and within half an hour they were gone. A little later a Guardsman walked by wearing them. He swore he had found them elsewhere and already his name was inscribed across the back in large black letters. Some of the most sought-after articles were the waterproof overboots that were much prized as a means of preventing trench foot. To take them off and leave them unattended was taken as an indication that you no longer had any further use for them. Courage was measured in two ways. First there was the extent of your ability to ‘hack it’; to keep going in adverse conditions. That you failed to hack it was almost the worst thing that could be said of you. Second there was the size and quality of your ‘bottle’. This was really old-fashioned daring. People who charged machine gun posts armed only with a fixed bayonet had a ‘lot of bottle’. That you ‘bottled out’ was definitely the worst thing that could be said of you. The most useful military word was ‘kit’. The military applied it to everything from a comporation tin-opener to a Hercules transport plane. This could be carried to extremes though. We heard one officer referring to his girlfriend as ‘a good bit of kit’.

When it came to the nastier side of their trade the military tended to go in for euphemisms. Apart from the SAS who invariably used direct terminology, you rarely heard people talk about killing Argentinians. They ‘took them out’, ‘wasted’ them or ‘blew them away’. Troops were never shelled. They were ‘malleted’, ‘banjoed’ or ‘brassed up’. It did not sound too alarming to hear over the ship’s tannoy that there was some ‘air activity’ thirty miles away until you realized that it meant some Argentine aircraft were minutes away from bombing you. To make the experience less harrowing, the incoming raiders were often called ‘dago airways’ in the running commentaries that went on during the attacks on Fearless. ‘We have some good news and some bad news,’ said a naval officer over the tannoy one day. ‘The good news is that four Argentinian aircraft are approaching from the west presenting excellent targets for our Harriers and missiles. The bad news is that they are Super Etendards carrying Exocet.’ Nothing was known by its real name. Food was ‘scran’ or ‘scoff’. The sea was the ‘oggin’ and our cabins were ‘pits’ or ‘grots’.

One of the reasons all this terminology sounded so odd was that the military was a foreign country to most of us. Because the days of national service were long gone few of the journalists knew what sort of men they were and how the Army and Navy operated. Having worked in Northern Ireland was not much of a help as it has been recent government policy to shield the Army from publicity and to prevent the emergence of any military ‘personalities’. In the absence of a conventional conflict for so long, the picture the public has of the upper reaches of the military has grown so faint as to be almost invisible. The heads of the services who sprung to prominence during the conflict were unknown to most people.

In view of this lack of information we tended to make crude assumptions about what these men would be like. Most of the battalion commanders had been educated at the better-known public schools and had gone straight into the Army. The Para and Marine commanding officers tended to be practical, spartan men who shared all the discomforts their men had to put up with. We were surprised when we went ashore to see 42 Commando’s CO, Lt.-Col Vaux, carrying a pack not much smaller than those of the ‘booties’ around him.

Although the officers shared the lives of the men and a close relationship grew up between them, at the end of the day they were still separated by an almost unbridgeable divide. Officers might call the subordinates by their Christian names when they were on their own together but it would never happen in public. The officers joined the forces as a career, the men as a job. The great majority of the soldiers knew when they joined up that they were in the ranks for the duration of their army lives, and for most of them it did not matter. To make the leap from the ranks meant taking examinations, including a knives and forks test to gauge your suitability for the rigours of the officers’ mess. ‘There are occasions when it is permissible, almost desirable, to throw a pint of beer over your neighbour’s head at dinner,’ a Marine lieutenant explained. ‘There are other times when it is not.’ The Parachute Regiment was the keenest to commission good NCOs and at least three majors in the campaign had joined the Army as privates.

We knew little about the men at the top of the chain of command, for Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse, Commander-in-Chief Fleet, ran the war from the Navy’s operations’ headquarters, an underground bunker at Northwood, in north-west London. The Task Force commander was Rear Admiral John Woodward, who was based throughout the war on HMS Hermes, the older of the two aircraft carriers with the fleet. He was called ‘Sandy’ because of his reddish hair and was the primus inter pares among the Task Force commanders. Both he and General Moore answered to Fieldhouse, but although Moore was in charge of the land forces, the local operation came under Woodward’s control. He was a retiring man, who played chess and solved mathematical problems as a hobby. Early on in the campaign his methods started to draw criticism from the Army. Most of it stemmed from Woodward’s preoccupation with the air and sea war and his determination to keep the losses of the fleet to a minimum. His nickname among some members of the land forces, and indeed some of the Navy too who were on the ships in San Carlos Water taking a daily battering from the Argentine jets, was ‘Windy Woodward’. He was awarded the ‘Burma Star’ for keeping the carriers so far east. It is hard to see what other course was open to him. For the British to win the war it was vital for them to have aeroplanes and if one or the other of the carriers was sunk the war would almost certainly have been at an end. Woodward’s first obligation was to keep Hermes and Invincible and the Harriers they carried safe, but by doing so he won few friends on the ground.

In some ways Woodward personified the Navy’s aloofness compared with the more relaxed attitude of the Army, and its gaucheness in dealing with the press. Northern Ireland had taught the Marines and Paras the power of publicity. The Navy, on the other hand, rarely came across the media, except perhaps once a year when the local television station turned up to film the gun race. Soon after the taking of South Georgia Woodward told the reporters on Hermes that the Task Force was now ready for the ‘heavy punch’ against the invaders and issued a public warning to the Argentinians. ‘If you want to get out I suggest you do so now,’ he said. ‘Once we arrive the only way home will be by courtesy of the Royal Navy.’ This was rousing quotable stuff and it quickly earned him a rebuke from Northwood for appearing too belligerent. A meeting with him a few days after the incident gave the impression of a nice, slightly naïve man. ‘I don’t regard myself as the hawk-eyed, sharp-nosed hard military man leading a battle fleet into the annals of history,’ he said. ‘I am very astonished to find myself in this position. I am an ordinary person who lives in south-west London in suburbia and I have been a virtual civil servant for the past three years commuting into London every day.’ Whether this peace-mongering appeased Northwood we never learnt but after that Woodward stopped talking to the press.

Maj.-Gen. Jeremy Moore was a small, lean man who bristled with energy. He was the Marines’ most decorated serving officer, having won a Military Cross in Malaya in 1950 and a bar twelve years later for commanding an amphibious assault against rebels in Brunei. Moore led a company of Marines in two small river boats in a surprise attack on 350 rebels who were holding British civilians hostage. They killed scores of them, lost five men themselves and rescued the prisoners. He was awarded an OBE for his part in Operation Motorman which ended the no-go areas in Northern Ireland. Moore was a religious man and liked to quote from Bonhoeffer as well as von Clausewitz. He was reputed to carry a Bible in his breast pocket. He liked to get around the battlefield and regularly flew up the mountains to check on the progress of the war from the front line, wandering around in a khaki forage cap and a kit bag with ‘Moore’ on the back. The lack of insignia on his uniform added to his air of authority. His role in the war was that of a logistician and administrator. He came out to the Falklands to act as a buffer between Woodward and Thompson and their masters in London and to smooth relations between the land force and the fleet. He said afterwards: ‘I had to take the political pressure off Julian’s back. He was involved in constant referring upwards to all levels in London and the fleet. It was his job to concentrate on the build-up for the attack on Stanley.’

Julian Thompson was the most obviously intelligent of the commanders; quotable, brisk and amusing. Despite leading a sure-footed campaign, he claimed not to have derived much pleasure from it. Sitting in his office in Port Stanley, he said: ‘I’m always reminded of the saying of Robert E. Lee. “It is a good thing that war is so terrible otherwise we would enjoy it too much.”’ Among the half-dozen recurring military maxims of the campaign, this was one of the favourites. Thompson was the commander with the most claim to be the architect of the victory. It was his plan. He chose the landing site and the route that the troops would follow to Stanley, aided all along by the SAS and SBS teams who were helicoptered on to the islands on 1 May to reconnoitre around Port Stanley, San Carlos, Goose Green and Port Howard. It was a conventional plan but it had its subtleties and it worked.

Rivalry between the components of the Task Force was endemic. It started at the very bottom of the military structure, with one platoon speaking disparagingly about the abilities of another, and spread upwards. One battalion in a regiment would try and outdo the other. At various points the rivals would come together against a common ‘enemy’ so that the Marines on occasion formed a united front against the Paras and in turn the whole of 3 Commando Brigade looked down slightly on the Guards and Gurkhas. At the top of the structure the Army would join forces occasionally to snipe at the Navy. The one thing everybody agreed on was that the RAF had not distinguished themselves. The Vulcan bombing raids on Port Stanley airfield provoked widespread hilarity. The Navy pilots on the other hand, got nothing but admiration and praise

When the war was over General Moore, inevitably quoting Wellington, said it had been ‘a close run thing’. When the fleet set sail it seemed impossible the Argentinians could win. After it was over it was difficult to see how they had lost. Their weapons were just as good as those of the British and better in some cases. They had two months to prepare their defences and at the start of the war they outnumbered their attackers by three to one, a direct inversion of the odds that conventional military wisdom dictates as a prerequisite for success. They had nothing like the logistical problems that beset their attackers and right to the end they were getting nightly visits from C130 transport planes flying in from the mainland. The myth of starving and disease-ridden Argentine conscripts was one that rankled with Task Force troops when they discovered that the defenders were in fact rather better fed than they were. The mistake was letting the British establish a beach-head in the first place. In some ways the Argentinians were justified in thinking that their Air Force could drive the British back before the invasion took root. If the French had supplied more Exocets, if more of the bombs they dropped had exploded, then the course of the war could have changed utterly. The losses that the British did sustain shook the Task Force commanders. If every bomb which hit a ship on D Day had gone off, the momentum of the campaign would have been stalled and the return to diplomacy would have seemed the only option. The Navy’s view was that the fuses were set for one height but the Argentine pilots were dropping them at another, coming in too low to ‘arm’ them in an attempt to get underneath the canopy of missiles and small-arms fire that the fleet put up whenever the raiders appeared. If the fuses had been shorter, however, the pilots would have run the risk of blasting their own planes out of the sky.

Once the British were ashore, the Argentinians had a rack of natural defences stretching all the way from the beach-head back to Port Stanley which, if properly fortified and defended, could have held up the advance for months. Yet they did give away almost all the ground up to the gates of Stanley. Mount Kent, which dominates the east end of the island, was abandoned without a fight. When the Argentinians chose to make a stand they often ignored elementary rules of infantry combat. They poured resources into Mount Longdon but neglected to push out advance patrols or train artillery in front of the stronghold so that the Paras were able to move up to their positions unimpeded. Both the Argentinian and the British commanders said that in the end it was the destructive power of the British which forced the surrender: the thirty 105mm field pieces and the rapid-firing 4.5inch naval guns that rained shells on the capital and the defensive perimeter during the last days of the fighting. But by that stage the war was nearly over. The fundamental difference between the two sides was the quality of the infantry men. The paratroopers’ victory at Goose Green over an enemy three times as numerous took place with minimal artillery support and against a heavy and skilful Argentine bombardment. In the end the Argentinians were disinclined to fight even though their soldiers probably felt the justice of their cause as much as their attackers did. The bulk of the Army was conscripted, and when the shooting started the NCOs were incapable of keeping their men in the trenches. After Goose Green, and as the British moved closer and closer, they seemed to have been overtaken by a creeping fatalism. Looking down from Mount Longdon the officer commanding A Company of 3 Para reported: ‘For the company the following two days provided some “good sport”. Having become established on the feature we found ourselves almost in the middle of the enemy camp, being able to observe and bring down harassing fire on all the main enemy positions. The two company MFCs, Corporals Crowne and Baxter, called it an MFC’s dream. The enemy seemed to show little concern for this harassing fire, and even continued to drive to and from Moody Brook and Stanley at night with headlights when meeting the nightly C130 flights. The number of targets was so great that they could not all be engaged.’

The British, on the other hand, had troops that were not only well-trained but also had a pride in their abilities and a degree of determination that made the prospect of defeat almost intolerable. George Orwell wrote in Homage to Catalonia: ‘People forget that a soldier anywhere near the front line is usually too hungry or frightened or cold or above all too tired to care about the political origins of the war.’ The British were no ideologues. They were just better soldiers.

It has not taken long for the memories of the Falklands war to dim. The things that are still vivid are the noises: the perpetual wop-wop of helicopters, the buzz of artillery shells. Neither of us had been shelled before. Like everything in the war it was surprising how quickly you adapted to it, though no one ever got used to it.

We were only fired on for a few hours but we soon learned to distinguish between the whizz of outgoing fire and the whistle of incoming. We experienced brief moments of terror but knew that if we were properly dug in it would take a direct hit to kill us, although this was rumoured to have happened to one unlucky man who had his head knocked off by a shell. ‘His number was definitely on that one,’ the teller would invariably say, whenever the story was repeated. The smells are still easy to recall: the hot eye-watering blast of aviation spirit exhaust that hit you every time you got on and off a helicopter. The powdery tang of artillery smoke and the acrid smell of a hexamine fuel block. There are other ineradicable memories: the horrible stillness of dead bodies; the sight of a row of survivors from Ardent, their expressionless faces smeared a ghastly white with Flamazine anti-burn cream, lying on the floor of the Ajax Bay field dressing station.

The war was a profound experience but not a particularly revealing one. On the whole it tended to confirm the truth of clichés. It did bring out the best in people: courage in the case of the civilian crews of the troop ships who more than anyone had the right to wonder what on earth they were doing there; compassion and dedication in the doctors and nurses who tended the casualties.

And at times it was hellish. The nights were long, about fourteen hours of darkness in which there was nothing to do but sleep, for we were not allowed to show any lights after dusk in case we gave away our position. It was always numbingly cold. We lived with seven layers of clothing on our chests and three on our legs and slept in them all, and usually with our boots on too. But despite the cold and the wet and the uncertainty, like everyone in this winter war we always slept well.

1

The Empire Strikes Back

HMS Invincible edged away from the quayside shortly before 10 a.m. on Monday, 5 April, tugs and small chase boats buzzing around her like impatient flies (writes John Witherow). She moved grandly down the Portsmouth Channel, exchanging salutes with ships and acknowledging the cheers of thousands of people lining the rooftops, quays and beaches in the crisp spring sunshine. Union flags skipped and curled above blurred heads and caps were doffed in extravagant gestures. From the Admiral’s bridge we could see the lone Sea Harrier fixed to the ‘ski jump’, its nose pointing skywards. At the stern, helicopters squatted on the flight deck, their blades strapped back. The order for ‘Invincible’s Attention’ to the 500 men lining the deck in their best rig was swept away by the wind and they ‘came to’ like a group of conscripts on their first day’s drill. We moved away from the small boats, past the old sea forts and into the Channel. Behind us came HMS Hermes, the old warhorse, already looking stained and weatherbeaten. A small group of men, for once not caught up in the urgency of departure, stood staring back at ‘Pompey’, others gazed towards the horizon. It had been a long time since the country sailed to war.

The speed of developments since Argentina invaded the Falklands three days earlier had been breathtaking. Crewmen, called back at short notice from their winter sports, had clambered aboard carrying skis while others arrived with rucksacks from hiking holidays. Every available Sea Harrier had been grabbed and warehouses emptied of spares and food.

The departure, however, gave the men a chance to collect their thoughts. There was a slight sense of the absurd; of a Gilbert and Sullivan operetta with the might of the Royal Navy off to bloody the noses of who they referred to as ‘a bunch of bean-eaters’. But the tears in the eyes of the young man on the bridge were real enough and there was no doubt on board that we had to avenge a wrong and restore national pride. Alongside pictures of the ships in the Task Force someone had put up a notice: ‘The Empire Strikes Back’.

But would it come to a fight? We were confident we were off on a cruise, a piece of sabre-rattling to concentrate General Galtieri’s mind and hasten a diplomatic solution. The days of gunboat diplomacy were over and surely no one would be foolish enough to fight over some far-flung islands at the bottom of the world? Not everyone on board, however, was so convinced. Captain Jeremy Black said on the second day, while we were still within sight of land, that war was likely. He had to say this to prepare the crew for the worst, but he also identified the issue of sovereignty over the islands as the stumbling block to a peaceful settlement. In the end he was proved right.

Gradually the rather jolly outing began to appear less jolly and hearing a rating sing ‘Don’t cry for me Argentina’ lost its charm. The only two board games in the wardroom were Risk and Diplomacy. The latter was rarely played. Even the notice in the flying room which said ‘Due to the untimely death of Mae West all life preservers will be known as Dolly Partons’, became less amusing. We were simply more concerned with getting a life jacket. As the mood of the ship darkened the closer we moved to the Falklands, so the British bulldog spirit of affronted pride gave way to a greater degree of realism and apprehension.

The officers, and especially the pilots, though, remained pugnacious throughout. ‘I’ve been dying for ages to have a limited war,’ commented Lt.-Com. ‘Sharky’ Ward. ‘It enables us to sort out the chaff and cut through the red tape.’ A helicopter pilot, Lieutenant Darryl Whitehead, married two days before we sailed, added in a surprising aside: ‘I know it sounds a bit bloodthirsty, but I would like to drop a real depth charge on a real target.’

The ratings demonstrated a more understandable desire to stay alive. Officers would speak of them getting ‘the jitters on the lower decks’ and at times they looked distinctly nervous. The crew were careful to express their doubts out of earshot of the officers. On a visit to the frigate, HMS Broadsword, we asked junior ratings in their tiny mess in the bowels of the ship, ‘What do you think of it so far?’ ‘Rubbish,’ came the stock reply. ‘Do you want to go home?’ ‘Not ’alf,’ they said, more seriously. An officer stuck his head round the door. ‘Do you think we ought to kick the Argies off the Falklands, lads?’ he enquired encouragingly. ‘Yeah, they orta be taught a lesson,’ was the response. As we filed from the room one of the boys, no older than eighteen, winked.

But however nervous we became at times, the men were touched by that Portsmouth send-off and the mass of mail and the young girls demanding to be pen pals. They knew the country was united behind them and their tattoos ‘Made in Britain’ (or ‘Brewed in Essex’ on their beer guts) displayed their nationalism.

The pulse of the ship was taken daily by the Captain, like a caring family GP. Much later in the voyage, after the Belgrano and Sheffield were sunk, the question of morale was raised when he doubted the veracity of two pieces we had written. One hack had seen a rating sitting on the floor during the threat of an Exocet attack, tears rolling down his cheeks as he looked at a picture of his girlfriend, and another had told me that until Argentina fired that first missile all he knew about the country was that they ate corned beef and played football. Now he rated them. The captain found it hard to believe his men could behave or speak in such a way. In the cramped confines of a ship, where men lived cheek by jowl for months on end, discipline was essential; especially during a push-button war where seconds matter. By writing about the crew’s doubts the Captain thought discipline and morale would be undermined. One thousand men were crammed together on Invincible, from Prince Andrew, then second in line to the throne, to the lowliest rating from the Gorbals. Although there was interplay between the different ranks, their boundaries were jealously guarded. Most preferred it that way. Morale was certainly mercurial. It could ebb and flow according to ship ‘buzzes’, the internal word-of-mouth system that got messages around almost as fast as the tannoy. It was widely believed, for instance, there would be R and R (rest and recreation) at Mombasa then Rio de Janeiro. Spirits soared. When the speciousness of these rumours was exposed they plummeted. Such buzzes frequently seemed to originate from the cooks’ galley, inhabited by large red-faced chefs who dreamed up mischief as they stirred their pots.

As the Task Force moved south, Operation Corporate, as it was now known, became increasingly secretive. Naval ships with their supply vessels had been leaving Britain and Gibraltar over a period of days bound for the rendezvous point at Ascension Island. Radio silence was observed and vessels were darkened at night. The crew was told it could not mention the ship’s position, speed and accompanying vessels in letters home. Invincible, in fact, was travelling south on only one propeller at about fifteen knots. Almost as soon as we left Portsmouth one of the gear couplings of the giant engines had shattered and teams of engineers worked round the clock for two weeks to replace it by the time we reached Ascension. It was a remarkable effort that went unreported due to the Navy’s desire to keep everything from the Argentinians that could prove useful. For the first few days we hardly caught a glimpse of any other ships and we imagined a lonely voyage for 8,000 miles with empty horizons. Then Hermes moved closer and for the remainder of the journey we could see at least four or five vessels, their dull, grey shapes discernible against the skyline. It was not quite like scenes from The Cruel Sea, with warships hammering along with only a few cables between them, but it was oddly reassuring.

The secrecy reflected not only the Navy’s obsession with stealth but also the growing state of readiness for war. Harriers were flying more or less continually; rocketing a ‘splash target’ dragged behind the ship, firing a Sidewinder heat-seeking missile at a phosphorus flare, dropping bombs and feigning attacks on other ships to test their responses. Sea King helicopters flew endless missions, probing the oceans with their active sonars like huge insects dipping their probosces into the sea. They would look for unidentified shipping, throwing the £5m. machine around the sky. Besides searching for hostile submarines they acted as scouts for missile-carrying ships, doing ‘over the horizon targeting’ which involved popping up for a look and then getting out of radar contact, very fast. I was just recovering from a bout of sea-sickness in the Bay of Biscay (the first and last time) and could scarcely take my eyes off a fixed point three feet in front of me as the helicopter dropped from 400 feet to just above the waves in seconds. They had a favourite trick of allowing a guest to take the controls and then switching off the stabilizer. The aircraft would plunge wildly before the co-pilot took over. Outings would turn into sing-songs, with the four-man crew going through 820 Squadron’s repertory over their internal radios. Every flight ended with a return to ‘mother’, the pilots’ term for Invincible. The helicopter crewmen tended to be younger than the Harrier pilots, many of whom were in their mid-thirties and had years of experience flying Buccaneers and Phantom jets. The Sea King crews were wilder, liable to stand round the wardroom piano singing lewd songs and play fearsome games before crawling to bed.

One of the junior pilots was Sub-Lieutenant Prince Andrew, who had joined 820 Ringbolt Squadron (motto: Shield and Avenge) the previous October. The other pilots were fiercely protective, thinking it poor form to talk about him behind his back. The most one of his friends would say was that he had improved since his training days at Dartmouth, when he had appeared rather standoffish. At first he had avoided the journalists in the wardroom, slightly ill-at-ease with having the press at such close proximity, especially newspapers like the Sun and Daily Star which had hardly endeared themselves to the Royal family We had been told not to make the first move and after a while he approached us, curious about the working of the press and telling us how he had evaded the paparazzi with tricks ‘the length of his arm’, none of which he would disclose. Another of his friends said he actually liked appearing in the papers, and became slightly irritated if there was no photograph or harmless story about ‘Randy Andy’.

For a twenty-two-year-old he was a curious mixture of maturity and youth. His voice and mannerisms were strikingly similar to those of Prince Charles, although his sense of humour, always just below the surface, was more direct than Charles’s satirical approach. One one occasion he took great delight in telling the man from the Sun that he relaxed by playing snooker on a gyro-stabilized table – an age old joke in the Navy which none the less continues to find victims.

You could tell Andrew was in the wardroom when a film was being shown by the guffaws of laughter from the ‘stalls’. Not everything pleased him though. He walked out of the film The Rose starring Bette Midler as a drugged-up rock star muttering ‘silly cow’. He neither drank nor smoked, at least in public, and while looking relaxed among his fellow pilots was perhaps inevitably conscious of his position. It is hard to feel one of the boys when your flying overalls sport the name ‘HRH Prince Andrew’. He was known to his colleagues simply as ‘H’ and was delighted weeks later when he came ashore in Port Stanley and I referred to him as ‘H’. ‘I’ve been trying for ages to get you journalists to call me that,’ he laughed. From the interviews he gave in Stanley after the fighting had finished, it almost seemed as if a different character had emerged. He was more articulate than before and less self-conscious. Perhaps the endless flying, the responsibility and the danger had matured him.

Andrew was always smartly dressed. His clothes seemed that bit crisper than the rest of the officers’, and his hair was always well cut and the same length. We wondered if there was a hairdresser on board by Royal Appointment. The first day on board we were told that, ‘As far as we are concerned he is like anyone else. He is just another officer.’ It became apparent over a period of time that this was true. He flew dangerous missions to rescue a pilot from a ditched helicopter off Hermes and the survivors of the Atlantic Conveyor after she was hit by an Exocet. He was also apt to be called on to be ‘Exocet decoy’, flying his helicopter alongside Invincible to distract the missile and draw it away beneath the aircraft. It was a hazardous exercise that required a cool nerve, hovering twenty feet above the waves, ready to rise up above the missile’s (allegedly) maximum height of twenty-seven feet as it fizzed over the horizon just below the speed of sound. On the day Sheffield was hit, Invincible fired chaff from near the bridge that almost brought down the Prince’s helicopter as he flew alongside. Piloting a helicopter in the South Atlantic was a dangerous operation and twenty were lost, including four Sea Kings which ditched in the ocean. But there was never any suggestion that Andrew did any more or less than the other pilots. To have treated him differently would have undermined his confidence and alienated the rest of the squadron.

On Good Friday, just four days after we sailed from Portsmouth, we heard for the first time the harsh, rasping note of the klaxon calling the ship to action stations. Men rushed down passages, dragging anti-flash hoods over their heads and putting on white elbow-length gloves. The urgency that the klaxon conveyed was contagious and you would find yourself running, slamming down hatches as a disembodied voice kept repeating, ‘Action stations, action stations. Assume NBCD state one. Condition Zulu.’ The initials referred to nuclear, biological and chemical defences, which meant making the ship airtight from attack. Condition Zulu meant all the hatches and doors had to be sealed, a higher state of alert than ‘yankee’. Sealing up Invincible could take anything between ten to twenty-five minutes, depending on the training of the crew. Once completed it was rather like being locked in a vast tomb, knowing escape would be hindered by sealed decks with scores of men competing to get through the ‘kidney hatches’. At first we found ourselves assigned to the Damage Control Centre of the ship during action stations. This was presided over by Lt.-Com. Andy Holland, known to everyone as ‘Damage’, who gaily chattered about Invincible being able to take five Exocet hits before sinking. After some thought this seemed a bad place to be. It was right in the centre of the ship and at Exocet height. Discussing the safest position during threat of attack became a pastime, rather in the manner that overweight people discuss the merits of diets. The press wandered around the ship debating the chief targets, sometimes watching what was going on from the Admiral’s bridge and at other times seeking refuge in the Captain’s day cabin, lying on the carpets and staring at the bulkhead.

But at least we could move around in search of safety. Most of the crew had no choice but to stay in their assigned positions sweating it out. Many would try and sleep. Others would just lie there, write letters, read girlie magazines or play cards. Some were distinguishable only by their names written across the forehead of their white anti-flash hood, disguising all but their eyes. It was possible to go for days, even weeks, without tasting the salt on your lips or feeling the wind. The weather throughout continued to belie all predictions. Instead of raging seas we had fog and instead of sleet we had crisp sunny days. There were one or two gales but down in the bowels of Invincible, fitted with stabilizers, the roll was barely discernible. Steaming along in a large British warship had as much to do with the sea as flying has with travel in a jumbo jet. At times, it seemed, we might as well have been in a submarine. The sense of vulnerability, even claustrophobia, was impossible to avoid. Modern warships have abandoned armour plating, taking the view that the money is better spent on missile defences. One hair-raising theory that ‘Damage’ told us about the light construction of Invincible, was that an Exocet could pass right through without exploding. No one seemed keen to test the theory.

I had acquired a small cabin at the stern of the ship, just above the waterline. The escape routes from this cubicle were negligible. You had to move down a passage, through several sealed doors and then up ladders. ‘It’s not worth it,’ one sub-lieutenant told me. ‘All the doors will buckle if we’re hit and you’ll never get out.’ At the outset the hacks had been placed in the Admiral’s offices. This was rather like sleeping in a canning factory during an earth tremor. The rooms were full of filing cabinets and as the ship vibrated the files reverberated, as in an outlandish and off-key tintinnabulation. I tried sleeping with ear-defenders and then with cotton wool ear plugs. Neither was effective. We tried to locate the root of the noises, sticking sheets of paper between the cabinets – also with no success. Gareth Parry of the Guardian struggled naked over desk tops in the middle of the night, tapping the ceiling in a futile attempt to pinpoint a particularly irritating rattle. He retired to his camp bed muttering, ‘Sleep is release. The nightmare starts when we wake up.’

Apart from the calls to action stations, training exercises were given greater verisimilitude with the addition of smoke canisters, thunderflashes and one pound scare charges dropped alongside the ship. ‘We’ve got to give the men the smell of cordite,’ the captain said. The mood of impending struggle was heightened with notices recommending the crew to make out their wills and ensure the name of their next of kin was up-to-date on official documents. We were issued with identity discs which gave rank, name and blood group. Later on we had to carry at all times a life jacket at our waist and a bright orange survival suit. Anti-flash hoods were worn relaxed around necks, like grubby cravats.

Many crewmen received brief courses in first aid. The ship’s surgeon, Bob Clarke, gave a humorous account on television of how to shove morphine injections into your leg, ending the programme with a smile and saying ‘have a good war’. Although extra supplies of plasma, morphine, antibiotics, plaster of pans and intravenous fluids were on board, Clarke said cheerfully: ‘We’ll decide those people who are worth saving, and make it as comfortable as possible for those who are not.’ Potential hazards from whiplash, such as mirrors, glasses, and loose objects, were removed and flammable material like curtains and cushions were stowed away. Invincible was gradually transformed from a relatively luxurious craft, certainly far more luxurious than we had been led to expect, into an austere fighting unit, prepared for the worst.

I remember sitting in the wardroom at the end of April watching the closed-circuit television churn out a more or less continual diet of soap opera, war films, Tom and Jerry cartoons and extracts from comedy shows. Pilots, wearing their green one-piece overalls or rubber ‘goon suits’ to protect them against the freezing South Atlantic, lounged casually in armchairs. Some carried 9mm Browning pistols in shoulder holsters. Around them coffee tables had been piled together and tied to pillars with string. The landscape watercolours had gone from the walls and the crests above the bar removed. The cabinet case which had displayed relics of the triumphs of former HMS Invincible’s (including the victory off the Falklands in 1914) was now covered with brown paper on which cartoons and new trophies had been drawn, including a whale for 820 Squadron which had depth-charged one in mistake for a hostile submarine. Television programmes started with a picture of a topless girl accompanied by a Welsh male-voice choir. Someone said they used to show extracts of Emmanuelle before senior officers addressed the crew to ensure there was an audience.

But as we moved south to Ascension life remained good. There were drinks in the evening before dinner, a good wine list, and a four-course meal invariably followed by port. Films were shown three times a week on the screen in the dining room or wardroom. There were cocktails on the quarterdeck as the sun dipped over the horizon and sing-songs. What a way to go to war, we all thought, without actually thinking we would.

Invincible, like most large naval ships, was a self-contained world. It had its own doctors, dentists, library, television, bars, shop and entertainment. There was even a Chinese cobbler, tailor and laundry, which the fourteen Chinese on board adopted as their action station. There were hundreds of Hong Kong Chinese in the Task Force, mainly in the Royal Fleet Auxiliary ships, which sailed alongside, supplying the warships with food and fuel. On one, Sir Geraint, we were served meals by a nervous Chinese steward wearing a tin helmet, his own protest at being thrust into such a war.

Different ranks would be divided into their own messes. One night with the petty officers the journalists became the butt of all the good-humoured jokes, staggering out without our ties which joined an already impressive array of trophies. Even though they were rationed to three cans of beer a day, they would not allow us to buy a drink. Whenever a glass of lager appeared someone would produce a small bottle and pour a substance into it with a grin. They cursed the officers as incompetent, the ship as badly designed and their fate as grim. None of them really wanted to fight but if they had to they would.

At the Equator we were summoned to meet King Neptune and his court, who arrived on the flight deck on the hydraulic lift used for the Harriers and Sea Kings. Several were sentenced to have a foul substance smeared on their faces and dumped backwards into a canvas swimming pool. Among the victims were the Captain, Prince Andrew, the pressmen and their ‘minder’, the Ministry of Defence press officer who had taken to the bridge in the futile hope of escaping the ‘policemen’ who roamed the ship.

On 16 April Ascension emerged from the Atlantic, a barren volcanic rock basking in the tropical sun. Instead of the Task Force fleet anchored offshore as we had expected, there were only a few ships, including HMS Fearless, the home of Commodore Michael Clapp and the future base of Maj.-Gen. Jeremy Moore. The rest of the fleet, it later emerged, had moved on at speed when it appeared that a diplomatic settlement was likely. The government wanted to get as many ships as far south as possible in case an agreement ruled they could move no closer to the Falklands. There was certainly a sense of urgency. Before we had anchored, helicopters were ferrying out supplies, slung beneath the aircraft like huge shopping bags. In the distance Hercules could be seen taking off and landing at Wideawake airfield. Crewmen took the opportunity to drop a line over the stern and sat up all night, catching fish, including a shark which broke a rod in three places. The only excitement came when two chefs from a supply ship who were taking the air spotted what they thought was a periscope and for a couple of hours threw the fleet into pandemonium. Hermes and other ships went to action stations as frigates and helicopters pursued a solid sonar contact travelling at fifteen knots. ‘At that speed it’s got to be nuclear-powered,’ one officer said authoritatively. We all wondered if we had found a Russian submarine sneaking in for a close-up. Their Tupolev aircraft, after all, had for some time been brazenly buzzing the fleet taking photographs. But after some heavy ‘pinging’ with sonar it was decided the underwater object was a whale and the two chefs had been hallucinating. Whales, in fact, got a pretty hard time all the way down. They were always being mistaken for submarines and being depth-charged and torpedoed. It became so common to detect them that one of the first and few jokes of the war was ‘It’s all over lads. The whales have surrendered.’

Instead of spending several days at Ascension, as planned, Invincible suddenly upped anchor and set off south on 18 April. Captain J.J. Black had said there was no Rubicon in the operation, but it suddenly seemed we had passed the point of no return and war appeared likely. The Captain was a master of the colourful, pithy phrase. Although at the outset he said ‘we’ll piss it’ he was undoubtedly concerned and had pinpointed the Super Etendards carrying Exocets as a major threat. A large, slightly balding man with sharp blue eyes, he had an American-style baseball cap with J.J. Black emblazoned across the back, which he sometimes wore on top of his white anti-flash hood, and drank tea from a mug with ‘Boss’ on the side. He was a thoughtful seaman who had seen service in Korea, Malaya and Borneo and had drawn up the rules of engagement for war. Apart from speaking German and French, he was teaching himself Spanish. Like many military men he saw the value of the press to help the war effort but was not happy if that press freedom strayed into sensitive areas. On one occasion he described us as one of his weapons systems in the fight against Argentina.

The Captain said that Brilliant, Glasgow, Sheffield and Coventry had been waiting for us at Ascension but had moved south at speed ‘to stake out a line’ in case of a diplomatic settlement. We then sailed with Hermes, which Admiral Sandy Woodward had joined from Glamorgan, Broadsword, Alacrity and several supply vessels. The Task Force was moving south towards the Falklands to establish air and sea superiority before the amphibious forces followed, lessening the risk to unprotected troops.