По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

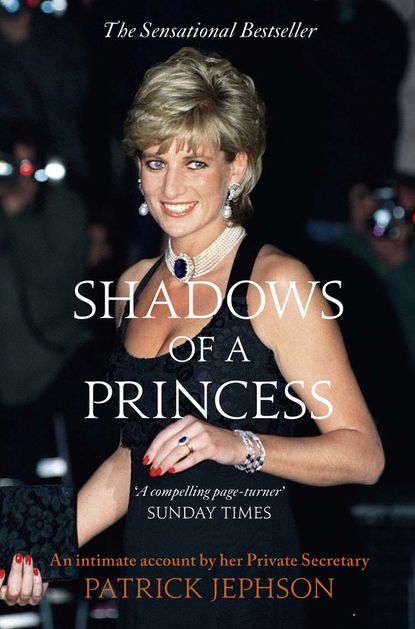

Shadows of a Princess

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

My first royal tour marked the end of my apprenticeship. There were still mountains of experience to climb. If I served her for a hundred years, I would still have much to learn about the Princess of Wales, and even more about the reactions she sparked in others. At last, however, I had the tour labels on my briefcase; I could swap tall stories with the best of them. Even more importantly, I had shared with the Princess the pressures and prolonged proximity that only foreign tours provide, especially difficult ones, which this definitely had been.

I had passed through a barrier of acceptability – one of many on the twisting and ultimately futile path to royal intimacy. From now on our relationship would be slightly different. She began to see through my mask of deference and I began to see through her saintly image.

The most significant change was the one least discussed. To travel with the Prince and Princess at that time was to learn, inescapably, the truth of their growing estrangement. In the office it had been almost possible to pretend that all was well. On the road in Britain I had been supporting only one half of what was still seen as a formidable double act. There was nothing to stop me arguing – as I did – that press speculation about problems in the marriage was offensive and inaccurate. The whole issue could be ignored in the comforting round of day-to-day business.

This was true no longer. I had arranged the separate accommodation and sweated to ensure the hermetic separation of his and her programmes, required for all but a few joint appearances. In Dubai I had been summoned into the cabin of the Princess’s departing jet to be given a farewell that was effusive and undeniably a pact of loyalty as I stayed behind with the Prince. I had witnessed with naive alarm the small, telltale signs of mutual antipathy that were soon to become public knowledge – averted eyes, defiantly uncoordinated walkabouts, competitive glad-handing.

Eventually, when she was travelling on solo tours, there was a welcome outbreak of informality in the Princess’s attitude towards me. Instead of the large numbers of their joint household who had previously paraded to greet her in the morning, she would find only me waiting at her door. I would be invited in, to steal extra breakfast, hear gossip from her phone calls, answer questions on the day’s business and compliment – or assist with – the choice of outfit. She might try three different outfits before setting off for the day and would ask my opinion on each.

‘Patrick, what d’you think of this hat?’

‘Um … very royal, Ma’am.’

‘Thanks. I’ll change it!’

The same process would operate in reverse in the evening, when she might ask me to pour a glass of champagne and join her in an irreverent postmortem on the people and issues that had made most impression on her over the course of the day.

This was quite nice, as far as it went. I defy anyone employed by royalty not to feel even a fleeting glow of illicit pleasure at being invited to share such intimacies. As I was to discover to my cost, however, centuries of deference had not been built up just to make the important people feel more important. Deference protected the small people too, from royal favour too lightly granted and too quickly withdrawn. So I was wary, even as I joined in what was, after all, just her way of dealing with the demands her job placed on her.

When she had chopped up and disposed of the day’s new players she often returned to a favourite subject: her husband. I once read extracts to her from Philip Ziegler’s biography of Edward VIII, in which the Prince of Wales (as he then was) was described by a contemporary as ‘part child, part genius’. She leapt at the comparison, as she did at many descriptions of her husband in which he appeared as naive, self-indulgent or emotionally immature.

In fairness, these were adjectives she was quite quick to direct at almost any member of the male species, and she was not blind to the Prince’s many virtues, among which she always included a touching vulnerability. When she spoke of him fondly – which admittedly was rare – it was with regret that he allowed his good intentions and good ideas (she stopped short of genius) to be hijacked by unscrupulous hangers-on. It was no surprise that many of her fiercest critics were drawn from these sycophantic ranks.

Even in the terminal stages of the marriage, when she was ready one minute to regard him as a wayward son and the next as her cold-blooded persecutor, I never knew her criticism of him to carry lasting malice. Nor do I doubt that she would have responded with pleasure and secret relief to marital peace overtures. For reasons that became clearer as my knowledge of them grew, however, the Waleses sadly found that they had less to contribute to their marriage than its survival demanded.

Meanwhile romance, in any of its forms, was what the Princess quite reasonably craved. She felt that it was withheld by her husband – deliberately or through incapacity – and therefore she sought and found it elsewhere.

Sometimes she found it in flirtatiousness at work, where her feminine charm was employed with precision and deadly effect. I was not immune to extravagant remarks such as ‘Oh Patrick, you’re the moon and stars to me!’ – even if the sentiment they implied did not seem to last very long.

Sometimes she found it in the supportive but necessarily circumscribed proximity of her personal staff. Any form of physical contact was, of course, unthinkable, but she would sometimes allow us all a playful frisson as we were invited to help her tie her army boots or check an evening gown’s dodgy zip.

With rare but spectacular exceptions, she was very cautious about expressing the aridity of her love life. Sometimes, though, the banter with which the painful subject was made bearable would slip, and in a voice suddenly sad and reflective, she would say, ‘Sex is OK, but sex with love is the best, isn’t it?’ That was quite a tough one to answer.

Although these sources of consolation were safe, they were no real substitute for the pleasures and hazards of a passionate relationship. Instead she developed an ability to experience emotions vicariously, drawing on her existing skills as a shrewd people-watcher and a natural talent to be sympathetic. St Paul’s injunction to rejoice with those who rejoice and weep with those who weep might have been written for her. Sadly, joy is not an easy emotion to experience at second hand and after an initial expression of pleasure at another’s good fortune, she often found that it left her feeling envious and dissatisfied. This always seemed to be most pronounced in maternity wards. It did not take a genius to work out why.

In addition, she did find some consolation in well-documented liaisons with other men, most notably with James Hewitt, who already rode high in her affections when I joined her staff. He was a regular but discreet visitor to KP, although our paths seldom crossed. Sometimes when I was leaving the red-haired Captain would be arriving, emitting a palpable sense of unease and a nervous but winning smile.

Later, the Princess closely involved me in her attempts – by then – to distance herself from him. I even carried discouraging messages to him at his barracks when he was planning a newspaper revelation about their relationship ‘to put the record straight’ (something, incidentally, which I have never thought possible on practically any subject). In 1989, however, the affair was just one more thing to be ignored, another sign of our unhappy times.

Had I wanted to, I could have found out more and sometimes did, especially over a beer with a detective. I knew, however, that it was more important to be able to deny convincingly knowledge of anything that my boss might later wish she had not done. Being a royal conscience might be a wonderfully self-justifying job, but it would be a short one.

She was paranoid that her affair would be discovered – but only because it would weaken her moral superiority over her husband. She only admitted the affair with Hewitt after it had become public knowledge. After his return from the Gulf War in 1991, the Princess often visited Hewitt at his family home in Devon. She was terrified of being found out and I even warned the police that they might have to lie to cover up for her. I was shocked to hear myself say it, but they just smiled indulgently.

She wistfully imagined a house in the country – an idyllic domestic life for them both, full of children, dogs and horses – but when he became too besotted, she was embarrassed and realized he was a liability in the battle against her husband for public sympathy.

Although I chose to be ignorant at the time, and naive too, it was sadly obvious even to me that these desperate, ill-starred affairs shared Jane Austen’s description of adultery as merely consuming the participants with ‘universal longing’. As I watched her struggle with this longing, but also with conscience, duty and an enduring loyalty to her husband, I sometimes found it hard not to recognize some truth in her generally low opinion of men.

More than once I heard her reproduce a favourite and very second-hand phrase, picked up from TV, I guessed, but no less sincere for that: ‘All men are bastards!’ Sometimes, catching a flicker of reaction on my face, she might add, ‘Sorry, Patrick.’

I began to watch closely how the Princess coped with the strains of her predicament. She was not good at relaxing, although she devoted increasing amounts of time and energy to finding the ‘peace of mind’ she often told me she was searching for. Her luggage was always well stocked with the latest in a seemingly endless catalogue of remedies – for stress, sleeplessness and various unspecified deficiencies, aches and pains. There were numerous varieties of homoeopathic pills, tinctures and oils, all accompanied by scrappy instructions which she would sometimes read aloud to me in search of guidance I could not give.

Aromatherapy was a continuing fascination, which was not surprising given her love of perfumes, flowers and scented candles. Keen to share her belief in its revitalizing qualities, she once gave me some expensively prepared bath oil. It was a kind gesture, even if it did make the bath – and me – smell of Harpic to my uneducated nose.

An army of practitioners went in and out of favour. Among the masseurs, Stephen Twigg was a favourite. She believed that his trademark deep-tissue technique helped to relieve her of conveniently unspecific aches and pains caused by stress.

Colonic irrigation was another popular discovery, thanks to the Duchess of York. The semi-medical procedures and professional intimacy were highly attractive. So too was the skill and sympathy of the eminent Chrissie Fitzgerald, who so dexterously wielded the various tubes and solutions. The attraction, which survived for several years, waned abruptly as Chrissie’s treatment started to be accompanied by doses of robust common sense. Her crime, it appeared, was to be insufficiently sympathetic to the injustices of her royal client’s existence – perhaps because she had witnessed darker shades of the same misfortune further down the social scale. She also did not take kindly to the press attention which the Princess seemed powerless to stop bringing, literally, to her door. Chrissie was dropped abruptly, even brutally, soon afterwards. Others found it easier to keep to their script.

Fitness trainers such as Carolan Brown remained in favour until the Princess’s death, as did relays of astrologers. Some, however, such as psychotherapist Susie Orbach or self-improvement guru Anthony Robbins, found their work less conducive to the quick fix that she craved.

Sympathy and attention rather than reality were what the Princess sought. She paid no more than lip service to the alternative lifestyles on offer and did not embrace the complementary medicine philosophy in the way that her husband did. Nonetheless, if her exploration of her own health needs lacked conviction or direction, her attitude to her therapists did not. Their greatest value was in the attention they lavished on her.

Some became highly influential and coloured her thinking, with unpredictable results. Called upon to speak publicly on health or social issues, she would sometimes show an alarming tendency to recycle advice she had imperfectly understood from one of these unofficial sources. Following the thoughts of a current favourite, she once spoke convincingly of children’s status as ‘miniature adults’ – to the consternation of the patronage involved, which preferred to think of them as anything but.

Quite apart from the frustration it caused her official advisers, this hunger for guidance from dubious sources had a destructive effect on the Princess’s own judgement, a quality she did not lack when she applied herself. She sowed gossip and traded rumour with them and they in turn encouraged a sense of infallibility which undermined her innate sense of self-preservation. A blind belief in her own intuition increasingly became a substitute for balanced analysis, or even plain common sense.

It also undermined her sense of the ridiculous. ‘Do you know,’ she said to me one day in June 1992, ‘my astrologer says my husband will never be king!’ That may have been exactly what she wanted to hear at the time, but it did not appear to alter her husband’s daily routine one jot. Yet she continued to heed her astrologers’ predictions, the more dire the better, particularly where the Prince was concerned. Sure enough, she was rewarded with regular forecasts of helicopter crashes, skiing accidents and other calamities that obstinately refused to befall him – much to her relief, I have no doubt.

Ultimately she lost touch with reality in her restless desire for reassurance. In the last year of her life she was quoted in Le Monde as saying, ‘I don’t need to take advice from anyone. I trust my own instincts.’

The truth was, she consumed advice insatiably and, depending on her mood, she would take it from anyone. Her credulity seemed directly proportional to the thrill factor of whatever prediction she was being invited to believe – which made her pretty much like the rest of us, I reluctantly concluded.

Even so, I thought it important to affect a cheerful cynicism about every latest fad. My light-hearted attitude was intended to acknowledge the need for attention without conceding that she was anything other than physically fit as a fiddle. I never knew her to be genuinely ill for a single day. She kept her side of the pact by allowing – and maybe even welcoming – my theatrical disapproval as she swallowed the latest offerings from her army of alternative practitioners. As a reassuring contrast, I extolled the more traditional merits of hot whisky and a good book as aids to happy slumber. Perhaps sensibly, however, she avoided alcohol.

The real problem was that she had no safe substitute for the wise, supportive and unpaid company which, in the end, was the only medicine she really needed. Underneath the light-heartedness I was worried about her growing tendency to find pseudo-medical excuses for attracting attention and sympathy. She became increasingly indiscriminate in her search for physical remedies for emotional disorders. Complementary cures were freely interspersed with more conventional sleeping pills and stimulants.

The effect of these combinations was anybody’s guess, since no single doctor knew what she was dosing herself with, let alone controlled her intake. Deep-tissue massage and painful vitamin injections also became regular features of pre-tour preparations. Once, in a fit of hypochondria, she wangled an urgent MRI scan. Unsurprisingly, the scan confirmed my own less penetrating diagnosis: she was as fit as a fiddle.

Reassurances and remedies were all to little effect in lonely hotels and guest residences, however. All the pills in the world did not seem able to help then, and she fell back into less esoteric habits. Too often, time spent in her room supposedly relaxing was spent in obsessive phone calls – gossip with girlfriends; gossip and flirting with admirers; gossip and intrigue with palace staff back home; and, on the plus side, laughter and light relief with her children, whom she missed acutely whenever she was abroad without them.

Nothing she took seemed to dull her quick-wittedness, or her quick tongue. Depending on her mood, I found that she could be perceptive and thoughtful with her praise and encouragement, if a little inconsistent. Getting a pat on the back one day did not protect you from being kicked the day after for doing the same thing.

When she was unhappy, her natural suspicion and deviousness took control. Then her verbal skills were employed to hurt and confuse. When roused, she used words like tomahawks and her aim seldom failed. She would know, with a cat’s cunning, when to let you feel the claw in her velvet paw. Like the predator she sometimes was, she would stalk her victim, waiting for his or her attention to be distracted before striking.

Typically, we might be on a train about to arrive at our destination and my mind would be preoccupied with the practical demands of the next few minutes, when she would see her opportunity. Her voice would take on that tone of guileless inconsequentiality that always made the hairs stand up on the back of my neck.

‘Patrick, you never told me I’d been invited to speak at the Sprained Wrist Association AGM. I know you wouldn’t understand, but people with sprained wrists are excluded by society. I think we ought to make a speech about it.’

The opening volley was designed to saturate my defences. While still distractedly craning out of the window for a telltale sign of red carpet and a press posse, I would subconsciously assess the incoming missiles:

- She has deliberately chosen a bad moment for me. This kind of premeditation always spells trouble. Look out for the second salvo. (My God, I hope she doesn’t know about that business with her new car…)

- She is accusing me of deliberately concealing an invitation from her because I disapprove of it or because I am too lazy to research it. (Both true on occasions, as she probably knows.)

- Why the Sprained Wrist Association, for goodness’ sake? Aha – cherchez a handsome radial osteopath. Extra trouble: she loves to pretend you are jealous.

- Note that I am too insensitive to understand. This means I have missed a recent opportunity to be sympathetic, exacerbated by the fact that, unlike herself and people living with SWS (Sprained Wrist Syndrome), I have no idea what it is like to feel rejected.

- And now ‘we’ have to make a speech. This means a heap of exploratory work with the Department of Health (again) and probably a ruined weekend while I draft the speech (again). The speech will then be rejected because take your pick – she has gone off the osteopath/the Daily Mail says SWS is all in the mind/the astrologer forbids speeches during the current transit of Pluto/the Prince is patron of the Sprained Knee Association and we are making a show of not competing at the moment.