По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

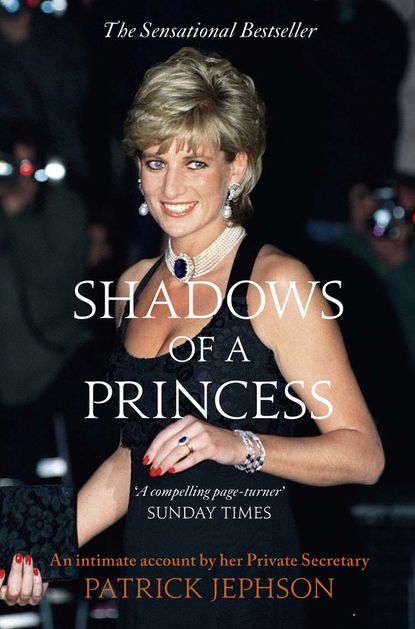

Shadows of a Princess

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Beginner’s luck,’ said Jo’s voice behind me.

I was half expecting the Princess to turn up at St James’s, but she did not. Nor did she phone me. I was not sure whether to be disappointed or relieved. I knew my Palace life would not really have begun until I spoke to her in my own right, rather than just as a job-hunter.

I went home late that night. As I passed KPI looked up the long drive and wondered what was going on behind the lighted windows. It looked cosy enough, but I remembered the Princess’s forced laughter and her clumsy jokes about her in-laws. It did not take a psychologist to see there was a great tension just below the surface.

Her popularity clearly gave her enormous power – I had felt it very strongly when I met her. But, like a toppled pyramid, it seemed an immense weight to rest on just her slim shoulders. Were others helping her carry that weight? Would I?

I already knew the answer to the second question. Even at this early stage I felt a loyalty to the Princess. For all her professional competence and innate nobility, there was an indefinable vulnerability about her that drew from me an unprompted wish to protect her. This developed into a complex mixture of duty and devotion which sometimes took more and sometimes less than the strict professional loyalty required, but which has never entirely disappeared.

As for the first question, I already had the glimmerings of an answer to that too. My observations at lunch in Buckingham Palace had given me a clue. If I felt that I, a junior minion in a junior household, was just tolerated by the old guard, how much more was that true of my boss. If I looked up from my own small patch of red carpet, I could see my experience reflected in that of the Princess, although hers was on a scale as different from mine as a lifetime is from a two-year secondment. Inside the organization of which she was a senior, popular and accomplished partner, she was just tolerated.

Being tolerated was fine, I supposed, but I had expected a degree of supervision, if not actual direction. At times I came to feel that even a measure of interest would have been welcome. Raised in disciplined organizations, I was surprised to discover the extent of the autonomy given to the junior households. Some form of structured, central co-ordination was the Philosopher’s Stone of royal strategic management and endless attempts were – and are – made to discover it. But even the sharpest sorcerer on the PR market is unlikely to work the magic for long. The base material of his potion is a thousand years of royal durability. It is hard, dull and unyielding, not readily open to transformation. It is strong too – but its strength is not the kind you would want to cuddle up to. The best he can hope to create is media gold – a fool’s delight.

Later, as events in the Waleses’ marriage moved from concern to crisis, tolerance became pained aloofness in some cases and outright distaste in others. In the end, however, it was the indifference that caused such harm. Opportunities to alter the downward spiral of events were squandered. Those who could have helped preferred too often to look away or distract themselves with the accustomed routines that had proved an effective bulwark against intrusive reality in the past. I knew and understood why. The need to confront unfamiliar and painfully intimate issues was deeply unwelcome to us courtiers as a class. What I resentfully saw as indifference I eventually realized often masked a genuine concern – and an equally genuine sense of complete impotence in the face of events that constantly defied the rules of familiar experience.

Part of what drove the Princess on to endure and exploit her public duties was her wish to earn the active recognition and approval of the family into which she had married. Sometimes with bitterness, but increasingly with a resigned acceptance, she complained to me that nobody ever told her she was doing a good job.

Oh, the papers praised her to the heavens, but they could knock her down again the next day. The public adored her, but theirs – she thought – was a fickle love, lavished on her hairdo as much as on her soul. In any case, she left it behind with the slam of her car door. Her staff could try to redress the balance, but the line between true praise and toadying was always perilously fine.

It was a cruel irony that the better she did her job, the more she felt resented by some of her in-laws, unable to stomach the idea that she was a channel for emotions they struggled to feel, let alone express. Very well: if she could not please them, she would please herself. Little wonder, then, that she grew to prefer working for her own benefit and, as she saw them, the emotional needs of humanity at large. It might be selfish and it lacked intellectual discipline. It could – and did – expose her to criticism from agents of an older royal order, fearful of the public sentiment (or sentimentality, in their eyes) which she increasingly stirred up. But better that, she thought – even unconsciously – than deny her need for a recognition that accepted her as she really was.

The liberal, compassionate and educated people who are the emerging face of royal authority might at this point feel entitled to a flicker of exasperation. ‘We did everything we could, but she was impossible!’

I can only reply, ‘Yes, you did. And yes, she was.’ But too many people who could have put things right did too little for too long. I will always believe it to be true: the Princess of Wales did not set out to rebel. What in the end was seen as her disaffection was what she did to compensate for a chronic feeling of rejection. Time and again, a small handful of sugarlumps would have been enough to lead this nervous thoroughbred back into the safety of the show ring. When none could be found for her, she set off into the crowd.

The organization I joined in 1988 nonetheless seemed, at least on the surface, to be united in its common aim of serving the Prince and Princess, both of whom for their part seemed equally united in keeping away from public gaze whatever private difficulties their marriage might have been experiencing. Even those well acquainted with the rumours, such as Georgina Howell, writing in the Sunday Times on 18 September 1988, could still reassure themselves that ‘Diana [has decided] as royal women so often have … to make the best of a cool marriage instead of fighting it.’ Ominously she added, ‘… but she lacks romance. The danger is that she may find it.’ Given what was later disclosed to Andrew Morton about the Princess’s love life at the time, this understatement is touching in its innocence. Captain Hewitt had already been on the scene for some time, carrying his own supply of romantic sugarlumps – and self-denial was never her strong point.

That first night, as I inched past the gates of KP in the London traffic, such thoughts were the merest inkling, easily pushed to the back of my mind. In the years that followed, however, they grew from idle speculation to grim reality.

Had I known it, the signs were all there from the beginning.

THREE (#ulink_58f5fc4a-10c4-5950-926f-7fc30203519e)

UNDER THE THUMB (#ulink_58f5fc4a-10c4-5950-926f-7fc30203519e)

The Princess’s footsteps sounded hurried. I had been listening to them for about five minutes now, standing in the semi-gloom of the KP hallway. Upstairs, she was preparing for a day of engagements out of London – what we called an ‘awayday’. Her high heels struck a distinctive note as she marched back and forth from her bedroom to the sitting room with, it seemed, several rapid diversions en route. To my nervous ears she was beginning to sound impatient. There was something increasingly agitated about her pacing.

Suddenly I heard a phone ring and there were a few minutes of silence, broken only by the low murmur of her voice. Then the footsteps started again, back to the bedroom, only this time more urgently, as I imagined her checking the time remaining before we were due to leave. She was fanatically punctual.

It was my first ‘real’ day at work – the first day on which I was going out with the Princess. This was my chance to begin to see the world through her eyes, to experience what it was like to be royal, only slightly second-hand.

In a pattern that was repeated a thousand times over the next seven years, I waited in the darkness at the foot of the stairs and listened to her flitting from room to room on the floor above, trying to guess what mood she was in and what sort of day lay ahead of us. The phone call could have been from anybody. The tone of her voice was neutral and I could not catch the words. I hoped whoever it was would not keep her talking – I had already learned enough to know she would be irritated if we started late. Best of all, whoever it was might make her laugh and send us smiling all the way to the helicopter.

A door opened and closed. At the top of the stairs she paused, straightening her skirt. Her blue Catherine Walker suit and executive blow-dry told you that here was a woman who was ready to take a grip on the day. The phone call must have been OK, because she cantered down the stairs, spotted the new boy and smiled, holding out her hand to me. It was to be seven years and a million royal handshakes later before we shook hands again. Then it was to say goodbye.

‘Hello again, Patrick. We didn’t scare you off then!’

I bowed and mumbled something.

‘This is a crazy place to work,’ she continued, heading rapidly for the front door, ‘but on this team we all started as outsiders, so we know how strange it feels to begin with.’

The lady-in-waiting and I followed her outside. After the darkness of the house the sun seemed dazzling. A car took us the short distance to Perk’s Field – a green offshoot of Hyde Park – where a shiny red helicopter was waiting. ‘Yuck!’ said the Princess through smiling teeth. ‘The flying tumble dryer. I just hope it won’t be bumpy. I hate bumps.’ Later I came to hate bumps too; not because they made me airsick, but because bumps, like rain or hail or the temperature of her tea, could quickly become the excuse for a mood. Moods were what we all dreaded.

As we clattered eastwards over London’s rooftops, the Princess ignored the view and concentrated on her copy of Vogue. The Queen’s Flight always kept a well-stocked magazine rack. After Vogue she might reach for a tabloid newspaper – usually the Daily Mail – and furrow her brow over Dempster. Often there was a royal story. That was a good way of starting a mood too.

Luckily it was noisy on our 30-minute flight, so there was no need to try to talk. On the occasions when I really had to communicate, shouting into her ear at close range made me paranoid about my breath. She had the same fear and regularly squirted Gold Spot into her famously perfect mouth.

Five minutes before landing the crewman signalled that we were nearly there. The Princess began rapid, expert work with the compact and lip gloss. With something of a shock, I realized the perfect complexion was not completely perfect close up. When I discovered her fluctuating intake of chocolate and sweets I could understand why – and sympathize too, as I contemplated the visible effects of a courtier’s diet on my own appearance.

A generous blast of hair spray always followed. Months later, when she was sharing the helicopter with her husband, she made (almost) all of us laugh by theatrically overdoing this emission of ozone-hostile gases.

As our destination – an Essex seaside town – hove into sight, she pulled out her briefing notes and gave them a cursory final glance. She was very good at her homework and usually swotted up the main points of the programme before she left the Palace. If her staff had done their planning properly, the day would run pretty much automatically. If she did not feel inspired to do more, all she really had to do was smile, shake hands and drop the occasional well-worn royal platitude. Except, of course, she usually was inspired to do more. Once on duty she hardly ever coasted. She took a professional pride in giving her public full value, which was one reason why they were ready to wait in vast numbers in any weather for even a fleeting glimpse of her.

As the helicopter’s rotor blades wound slowly to a stop, she undid her seatbelt and stooped by the door, waiting for it to be slid open, poised like an athlete before the starting gun. She gave a final tug to her jacket, smoothed her skirt and caught my eye. ‘Another episode in the everyday story of royal folk!’ she laughed, putting the newcomer at ease. Look, she was saying, I’m human, friendly, approachable. You’re really lucky to be working for me…

As I watched her step nimbly out of the helicopter into the excited noise and good-natured bustle of a busy day of good works, I had no trouble agreeing. Disenchantment – hers and mine – came only slowly. That day, the picture was brand new, glossy and colourful. As she visited a factory, a hospital and an old folks’ home I saw the royal celebrity at work: professional to her fingertips but still a flirt; ready to laugh with those who laughed – and ready to make them laugh when nerves got the better of them; ready to comfort those who were weeping.

Halfway through the day we stopped for lunch. Lunches on an engagement were usually planned as buffets so that she could circulate among as many guests as possible. But circulating and eating do not mix – you risk spraying sausage roll over people when you speak – so the Princess would ‘retire’ to a private room for a loo stop and a quick bite before joining the throng.

These short breaks were a great relaxation for her in the middle of a tiring day. ‘Have a drink, boys!’ she would say to me and the policeman if a bottle of wine had been left for us. She would usually restrict herself to fizzy water and nibble a sandwich, but if she was tense she might do real justice to the caterer’s pride and joy and eat forkfuls of salad and cold meat followed by pudding – or sometimes the other way round.

Without warning, she could be ravenous for sweet things. The wise lady-in-waiting carried fruit gums in her handbag and the chauffeur kept a stock of emergency chocolate in the car. I frequently watched her eat a whole bar of fruit-and-nut between engagements. Suddenly aware of her behaviour, she would insist on everyone else eating sweets too. No wonder I spent much of the time feeling queasy.

It was not until later that I recognized these mini-binges as comfort eating, vain attempts to console herself for her emotional hunger. The roots undoubtedly lay in childhood unhappiness. The broken home of her early years has been well documented and she spoke to me often of tensions with her father. ‘Once when he took me to school,’ she said, ‘I stood on the steps and screamed, “If you leave me here you don’t love me!”’

I did not probe into the Princess’s childhood, but in a way I had no need to. Photographs of the teenage Diana Spencer show her at a glance to be knowing, dull-eyed and self-conscious. Throughout my time with the Princess there were occasional signs of the scars of earlier traumas: insecurity in her attractiveness, a passionate need for unconditional love, an obsession with establishing emotional control, and a sabotaging approach to relationships. The distrust of men and the chronically poor image she had of herself told their own story.

The Princess was bulimic for most of the time I knew her. Despite a continuous battle with the condition, which she was popularly supposed to have won, she often suffered recurrent attacks. These were most frequent when the strains in her marriage were simultaneously driving her to comfort eating while fuelling her innate self-doubt.

Once – on a hungry day – she took a big bite at a prawn sandwich. A solitary prawn escaped and fell with deadly accuracy down her front, disappearing into her cleavage. She squeaked with surprise and looked inside her jacket. I waited for the prawn to reappear, but it failed to do so.

‘Bloody thing’s stuck!’ she said through a mouthful of sandwich.

‘Poor prawn,’ I said lamely.

‘Bloody lucky prawn!’ she corrected me, turning away to deal with the intruder. I took the hint. Modesty was for her to indulge in when she wanted to. It was not for me to question her absolute desirability, even in fun, even by a syllable.

Perhaps surprisingly, there was never a ban on food jokes. Maybe it was her way of dealing with the potential embarrassment of the whole subject. I was later struck by the courage – or foolhardiness – of her self-mocking reference to constantly ‘sticking my head down the loo’.

Later that day we flew back to London. As the helicopter lifted from the town park, so the tensions of the day lifted from her shoulders. It was instant party time. Now came the jokes and the gossip. Nobody cared about shouting. My newcomer’s ears struggled to believe what they heard. Was this the same Princess who an hour ago had been the saintly hospital visitor?

‘What d’you get if you cross a nun with an apple?’ she yelled above the engine noise.

‘I don’t know, Ma’am. What do you get if you cross a nun with an apple?’ I replied, looking dumbly at the lady-in-waiting to see if this was normal behaviour. Her determined smile indicated that it was.

‘A computer that won’t go down on you!’ shrieked the Princess, doubling up with mirth.

Even as I obediently joined in the laughter, I noted the sadness behind my new boss’s taste in humour. She would not know how to switch a computer on, let alone use it for long enough to see it crash; and as for the oral sex … as a joke, it was reassuringly remote. The daring and crudity gave her the necessary thrill. Even if she did not fully understand what she was saying, she knew it would shock and that was what she wanted. It was the safest of safe sex.