По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

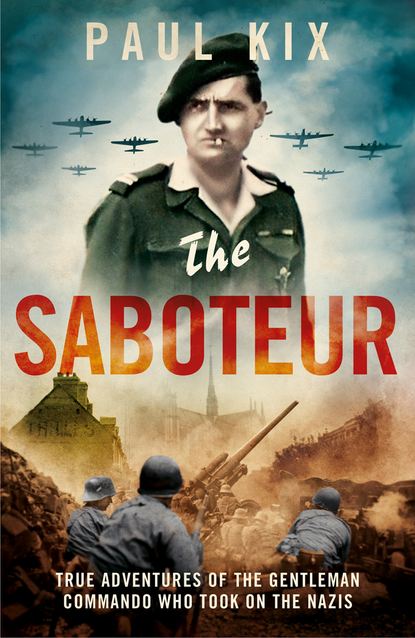

The Saboteur: True Adventures Of The Gentleman Commando Who Took On The Nazis

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In late February 1943, after roughly three months in prison, the British pilots with La Rochefoucauld heard that a man from His Majesty’s Government (#litres_trial_promo) awaited them in the visitors’ room. The three inmates smiled. Quickly, the British men gathered themselves and made for their meeting, with Robert calling after them, Don’t forget me, and begging them to mention that he wanted to meet de Gaulle and join the Free French. A short while later, the pilots returned to the cell, smirking, and Robert soon found out why.

He was called to meet with the British representative. This was likely a military attaché, Major Haslam (#litres_trial_promo), who made frequent trips to the camp in 1943. Once La Rochefoucauld reached the visitors’ room, the Brit profusely thanked him “for all you’ve done (#litres_trial_promo) to help my countrymen.” Robert was dumbfounded: What had he done? He’d served as the pilots’ interpreter, little more. But the representative went on and Robert figured the pilots had “grossly embellished (#litres_trial_promo) my role.” He tried to set the man straight, explaining that though he was happy to know the pilots, and even befriend them, his passage through Spain had no purpose other than getting to de Gaulle and joining the Free French.

The Brit stared at him, not upset that he had been misled, but seemingly working something out in his mind. At last, he said he would do his best to grant La Rochefoucauld’s wish. “I thanked him with all my heart,” La Rochefoucauld wrote, “and once back in the cell, fell into the arms of the pilots.” A few days later, he got on a truck with the airmen and departed for Madrid and the British embassy.

They arrived at night, the Spanish capital so brilliantly lit it shocked them; it had been months since they’d seen such iridescence. At the embassy they ate a “top-notch dinner,” La Rochefoucauld wrote, “then we were brought to our rooms, the dimensions and comfort of which seemed incredible.” An embassy staffer told them they would meet with Ambassador Hoare himself in the morning.

After a proper English breakfast, each man had his meeting. Hoare was aging and short (#litres_trial_promo), with the look of upper-class British severity about him: his gray hair trimmed and parted crisply to the right, his dress fastidious, and his manners formal. Hoare was ambitious and competitive (#litres_trial_promo); his taut frame reflected the tournament-level tennis he still played. He had been part of Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s cabinet (#litres_trial_promo), the secretary of the Home Office, and one of the key advisors to Chamberlain when he appeased Hitler in the Munich Agreement in 1938. Churchill dismissed Hoare when he became prime minister in 1940, offering Hoare the ambassadorship in Madrid that many in London saw as the old man’s proper banishment. Hoare seemed to wear this rejection (#litres_trial_promo) in his delicate facial features and his searching, almost wounded eyes. Still, his mission in Madrid had been to keep the pro-German Franco out of the war, and he had done his job with aplomb (#litres_trial_promo). Spain remained neutral, even after the Allies’ North African landings in November 1942, and Franco continued to allow the release of British troops and Resistance fighters from Miranda.

Because of his ease with the French language (#litres_trial_promo), Hoare had been the man in Chamberlain’s cabinet to sit next to French Prime Minister Léon Blum at a state luncheon, the two talking literature, and now in Madrid he opened the conversation with La Rochefoucauld in similarly “perfect French (#litres_trial_promo),” the fledgling résistant later wrote. “He was indeed aware of my plans to join up with the Free French forces in London but, without rushing, without ever opposing my determination, he revealed to me a sort of counter project.” During the First World War, Hoare had headed the British Secret Intelligence Service in Petrograd, Russia—he may have even originated a plot to kill Rasputin (#litres_trial_promo)—and still relished the dark arts of espionage. What would you say, Hoare asked Robert, to enlisting in a branch of the British special services that carried out missions in France?

La Rochefoucauld wasn’t sure what that implied, and so Hoare continued, revealing his proposition slowly.

“The British agents have competence and courage that are beyond reproach (#litres_trial_promo),” Hoare said. But their French, even if passable, was heavily accented. German agents found them out. So Great Britain had formed a new secret service, the likes of which the world had never before seen, training foreign nationals in London and then parachuting them back into their home countries where they fought the Nazis with—well, Hoare stressed that he could not disclose too much. But if the Frenchman agreed to join this new secret service, and if he passed its very demanding training procedures, all would be revealed.

The mystery intrigued Robert. It also tore at him. He had listened to de Gaulle for close to two years and lived by the general’s defiant statements to battle on. It had seemed at times that only de Gaulle spoke sanely about France and its future. But though he’d wished to be a soldier in the general’s army, what Robert really wanted, now that he thought about it, was simply to fight the Nazis. If the British could train and arm him as well if not better than de Gaulle—if the Brits had the staff and the money and the weapons—why not join the British? If Robert wanted to liberate France, did it really matter in whose name he did it?

Hoare could see the young man considering his options and asked, “How old are you?”

“Twenty-one,” La Rochefoucauld answered, which was not only a lie—he was nineteen—but revealed which way he was leaning. He wanted Hoare to think he was older and more experienced.

At last, Robert said he was honored by the offer, and he might like to join the new British agency. He wanted, however, when he arrived in London, to first ask de Gaulle what he thought. It was a presumptuous request, but Hoare nonetheless said such a thing could be arranged.

The next week, La Rochefoucauld flew to England.

CHAPTER 5 (#ub73d4e94-6ac9-5940-b968-e053d0fbfebe)

When he landed, military police shuttled him to southwest London, to an ornately Gothic building at Fitzhugh Grove euphemistically known as the London Reception Center (#litres_trial_promo), whose real name, the Royal Victoria Patriotic Building, still didn’t describe what actually happened there: namely, the harsh interrogation of incoming foreign nationals by MI6 officers. The hope was to flush out German spies (#litres_trial_promo) who, once identified, were either quarantined in windowless concrete cells or flipped into double agents—sending them back into the field with a supposed allegiance to the Nazis but a true fealty to Great Britain.

La Rochefoucauld’s interrogation opened with him giving the Brits a fake name—which may very well be why Robert Jean Renaud appeared in the Royal Victoria Patriotic files in March 1943 (#litres_trial_promo). He also said he was twenty-one. He would come to regret these statements as the interrogation stretched from one day to two (#litres_trial_promo), and then beyond. Though he eventually admitted to the officers his real identity, that only prolonged the questioning, because now the agents wanted to know why he had lied in the first place. And the answer seemed to be: because he was a nineteen-year-old who still acted like a boy, creating mischief amid authority figures. In some sense, deceiving the British was the same as climbing a lycée’s homeroom curtains. It was a fun thing to do.

The British officers in the Patriotic Building would later claim they didn’t rely on torture but used numerous “techniques” to get people to talk: forcing them to stand for hours and recount in mind-numbing detail how they had arrived or to sit in a painfully hardbacked chair and do the same; or filling up refugees with English tea and forbidding them to leave, seeing if their stories changed as their bladders cried for relief; or questioning applicants from sunup to sundown, or from sundown to sunup; or tag-teaming a refugee and playing good cop, bad cop (#litres_trial_promo). Robert remembered emerging from marathon sessions and talking to the “twenty or so fugitives there, in a situation similar to mine, who had come from various European countries.” The people he saw were some of the thirty thousand or so who ultimately filtered through the Patriotic Building during the war: men and women who in other lands were politicians or military personnel or just flat-out adventurers, washing ashore in England (#litres_trial_promo), sleeping in barracks, and awaiting their next interrogation slumped over on small benches, remnants of the building’s former life as a school for orphans (#litres_trial_promo).

La Rochefoucauld was there for eight days (#litres_trial_promo). In the end, an interrogating officer who spoke French knew of Robert’s family and its lineage, and soon he and the officer were chatting about the La Rochefoucaulds like old friends (#litres_trial_promo). Because the British espionage services brimmed with upper-class Englishmen, the spies identified with a Frenchman from the “right” sort of family, and it soon became evident that this nobleman was not a German agent. Robert was free to go.

A man waited for him as he left the grounds. He had a boy’s way (#litres_trial_promo) of smiling, turning up his lips without revealing his teeth, an attempt to give his slender build a tough veneer. His name was Eric Piquet-Wicks, and he helped oversee a branch of the new secret service that Ambassador Hoare had mentioned to La Rochefoucauld. His features had an almost ethereal fineness to them, but his personality was much hardier, all seafaring wanderlust (#litres_trial_promo). He was aging gracefully, the thin creases around his eyes and cheeks granting him the gravitas his smile did not. He wore a suit well (#litres_trial_promo).

Piquet-Wicks and La Rochefoucauld walked around the neighborhood, Robert taking in the spring air, free of the paranoid thoughts (#litres_trial_promo) of the last months, while Piquet-Wicks discussed his own life and how Robert might be able to help him.

Piquet-Wicks’s mother (#litres_trial_promo) was French. The name that many Brits pronounced Pick-it Wicks was in fact Pi-kay Wicks, after his mother, Alice Mercier-Piquet, of the port city of Calais. He was born in Colchester and split his formative education between England and France, earning his college degree, in Spanish, at a university in Barcelona and making him trilingual when he graduated in the middle of the 1930s. He found work, of all places, in the Philippines, on the island of Cebù, where he became the French consular agent. From there he moved to the Paris office of a multinational firm called Borax (#litres_trial_promo), which extracted mineral deposits from sites around the world. In Paris, Piquet-Wicks was the managing director of Borax Français, but he longed to be a spy.

After Britain declared war on Germany, Piquet-Wicks received a commission with the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, an infantry regiment. He was stationed in Northern Ireland and woefully bored. He seems to have approached MI5, Britain’s security service, which oversaw domestic threats, to inquire about how he could best serve the agency, because it had a report (#litres_trial_promo) on him. The agency described him as an “adventurer” who had once used his military permit at the Alexandra Hotel in Hyde Park as the means to gain whiskey; he’d told the barman it wouldn’t be long before he worked for MI5. The report also said that before the war Piquet-Wicks had had pro-Nazi leanings, but that wasn’t the reason the agency stayed away from hiring him. “We considered him unsuitable for employment on Intelligence duties, in view of his indiscreet behavior (#litres_trial_promo),” the report stated.

MI6, the famed spy agency, then began asking about Piquet-Wicks in July 1940, the idea being that he was an intelligent if unstable man whose dexterity with languages—he also knew some Portuguese and Italian—might still benefit Britain. But again a concern over indiscretion surfaced, and MI6 kept its distance, with one agent even saying Piquet-Wicks didn’t have “enough guts to be an adventurer (#litres_trial_promo).”

He may have stayed in Northern Ireland, living in a former brewery where “it was difficult to feel embarked in a war of … consequence (#litres_trial_promo),” he later wrote, were it not for a new security service that was in need of qualified agents.

Piquet-Wicks’s new life began one day in April 1941 at 3 a.m., pulling night duty in Belfast as a punishment for marching too far ahead of his company in drills. The phone rang. He didn’t think to answer it, but the ringing wouldn’t stop and so he picked up.

“Have you a Second Lieutenant Piquet-Wicks?” a man said. Piquet-Wicks thought this had to be someone in the mess pulling his leg.

“I am the poor bastard,” he said.

The shocked splutterings on the other end made Piquet-Wicks realize this was someone official. Startled, he hung up.

The phone rang again.

“Inniskilling,” Piquet-Wicks said, trying another tactic.

“Have you a Second Lieutenant Piquet-Wicks with the battalion?” the same voice said, but angrier.

“Yes, sir.”

“Where is he? A few minutes ago I had someone on this line. I thought—”

Piquet-Wicks broke in, saying this was the night duty officer speaking. “The officer you are calling is undoubtedly asleep,” he said. “Shall I wake him for you, sir?”

“Of course not, at this hour,” said the caller, who was a colonel from the Northern Ireland district. “Take note that he should report to the War Office … at 1500 hours on Friday the fourth.”

The War Office was in London, and the fourth was the next day.

In the morning, Piquet-Wicks went to his superior, to see what to make of the message. “I’m afraid you won’t be able to continue your disciplinary training as night duty officer,” the superior said, his eyes twinkling. “However, good luck and good-bye.”

If Piquet-Wicks were to make it to London, he would have to catch the next boat, which departed before he could properly gather all his things, or comprehend why he needed to rush to the capital.

When he arrived at the given room inside the War Office, he met with a general, who said the British were establishing a new department—unlike MI5 and MI6, and unlike anything seen before. “I was to be seconded to a secret organization,” Piquet-Wicks later wrote, “to become involved in events whose existence I had never suspected.”

On his walk now with La Rochefoucauld, almost two years later, Piquet-Wicks implied he would like Robert to work (#litres_trial_promo) under him, as an agent in his branch of this secret organization, which he had built up almost single-handedly. More details and the particulars of missions would be disclosed if and when La Rochefoucauld made it through training.

“Here is my address,” Piquet-Wicks said.

He was “surprisingly close to each (#litres_trial_promo) prospective agent,” he later admitted, and La Rochefoucauld sensed the humanity behind the spy’s implacable eyes. Like virtually every French agent whose life was to be guided and ultimately transformed by Eric Piquet-Wicks, Robert liked the man with the goofy smile (#litres_trial_promo) immensely. So he thought it best to level with him. He said he had to seek out de Gaulle and ask the general’s advice on joining a British agency out to save France.

Robert didn’t know how closely Piquet-Wicks worked with the Free French forces. He was taken aback when Piquet-Wicks not only agreed to the sensibility of the meeting but offered him directions to Carlton Gardens, de Gaulle’s headquarters in London.

“If you get to meet him (#litres_trial_promo),” Piquet-Wicks said, “ask him what you need to ask him, then come meet me.” The display of camaraderie eased La Rochefoucauld’s mind and pushed him ever closer to joining the British.

No. 4 Carlton Gardens (#litres_trial_promo) sat amid two blocks of impeccable terraced apartments, their white-stone façades overlooking St. James Park, the oldest of London’s eight Royal Parks. Built on the order of King George IV in the early 1800s and designed by architect John Nash (#litres_trial_promo), the rows of four-story buildings collectively called Carlton House Terrace had been home to many a proper Londoner (#litres_trial_promo) over the years—earls and lords and even Louis-Napoléon in 1839. The German embassy occupied 7–9 Carlton Gardens (#litres_trial_promo) until the outbreak of World War II. In 1941, during an air raid, a bomb fell on No. 2 Carlton House Terrace (#litres_trial_promo), leaving its roof open and exposed for the rest of the fighting. No. 4 Carlton Gardens housed de Gaulle’s Free French forces, and one didn’t need to look for the address to know who worked there. A French soldier (#litres_trial_promo) in full military fatigues, rifle at his side and a helmet on his head, stood guard outside the entrance, itself marked by the Cross of Lorraine, which the Knights Templar had once carried during the Crusades but which was now the symbol of the Free French movement.

Robert kept his appointment, arranged by the Brits, with an aide of de Gaulle’s. La Rochefoucauld mentioned his family name, “which may have possibly facilitated things (#litres_trial_promo),” he wrote, and because de Gaulle’s daily schedule allowed for fugitive Frenchmen who wanted to see him, Robert was told he would meet with the general that afternoon. He gulped.

The interior was all dark wood and high Gothic ceilings (#litres_trial_promo)—an airy space with lots of natural light but poor insulation. In the winter, the Free French, across four floors, each nearly three thousand square feet, shivered in their huge rooms.

When the hour came, the secretary asked La Rochefoucauld if he was ready, and they climbed an ornate stairwell to a landing where doors led first to the offices of De Gaulle’s aide-de-camp, and then past those to the general’s own quarters. La Rochefoucauld’s heart thrummed in his chest (#litres_trial_promo).

Then the door opened and there he was. The man whose voice over the last few years Robert had heard scores of times, The soul of Free France, La Rochefoucauld thought. He sat behind his desk, peering over his glasses, with a look that asked, Now what might this onewant? His presence filled the room (#litres_trial_promo). Everyone in London called him Le Grand Charles, due only in part to his towering height. Robert took in the office, uncluttered and organized, befitting a general, with a map of the world (#litres_trial_promo) pinned to the wall behind de Gaulle and one of France hanging to his right. Out of his large French windows, the general had a view of St. James Park.

He rose to greet La Rochefoucauld, unbending his immense frame and straightening to his full six feet five inches, a half-foot taller than the nineteen-year-old. He had an odd body, “a head like a pineapple (#litres_trial_promo) and hips like a woman’s,” as Alexander Cadogan, Britain’s permanent under-secretary at the Foreign Office, once put it. His trimmed half mustache, a hairy square on his upper lip, was not a good look for a man with such a long face. The severed patch of facial hair only drew attention to his high forehead, and rather than shave the mustache, de Gaulle had taken to wearing military caps in many photographs and official portraits. He was aware of his ungainliness. “We people are never quite at ease (#litres_trial_promo),” he once told a colleague. “I mean—giants. The chairs are always too small, the tables too low, the impression one makes too strong.” Perhaps because of this, the general had welcomed solitude in London, taken on few friends, and worked in Carlton Gardens most days from 9 a.m. until evening (#litres_trial_promo), which allowed him to see people like La Rochefoucauld but returned him home only in time to talk with his wife and perhaps kiss his two daughters good night.