По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

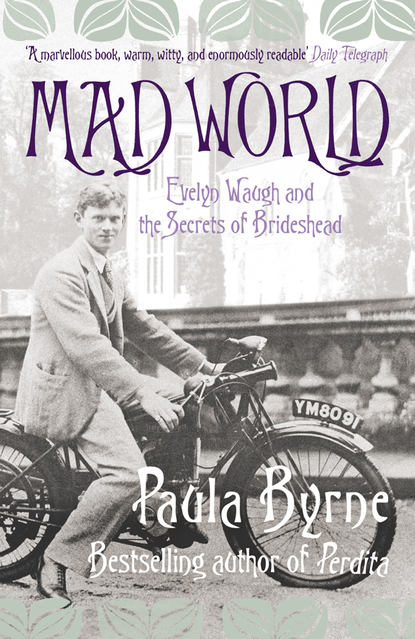

Mad World: Evelyn Waugh and the Secrets of Brideshead

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It was not merely the inferior student rooms that Evelyn minded, but the fact that it was difficult to form friendships so late in the year. Looking back, as he wrote his memoirs, he remembered his younger self as a somewhat romantic ‘lone explorer’, a rover on the fringes of various groups (‘sets’) of like-minded students. His letters at the time show a much less self-confident figure, desperately lonely, shy and ill at ease.

His contemporaries fell into two groups: those who were clever and dull, and those who were foolish and charming. Hertford College he found second-rate, respectable but dreary. It had none of the glamour of the more famous colleges such as Christ Church and Merton, though this had its advantages. It lacked the schoolboyish hooliganism of the larger colleges: ‘No one was ever debagged or had his rooms wrecked or his oak screwed up’ (undergraduate rooms had an inner door of baize and an outer of oak – if you did not wish to be disturbed, you closed the outer one, or ‘sported your oak’). A contemporary described Hertford as ‘rather earnest and lower-middle-class’. One of the main reasons Evelyn chose it was to save his father money.

This was not quite the romantic beginning that he had envisioned when as a schoolboy he had daydreamed about Oxford and prepared himself by reading novels such as Compton Mackenzie’s Sinister Street and Max Beerbohm’s Zuleika Dobson. For a sensitive boy with a strong aesthetic sensibility, Oxford had an irresistible aura of enchantment. He went up to the ‘varsity’ with his imagination aglow with literary associations. The sophisticated boys whom he came to know later treated Oxford with studied indifference and cool detachment. Their hearts had been left at Eton. For Evelyn, by contrast, product of a minor public school, there was magic in the beauty of Oxford, its ancient buildings of greys and golds, its tranquil, lush gardens and dreaming spires. ‘All I can say,’ he gushed to a friend shortly after his arrival, ‘is that it is immensely beautiful and immensely different from anything I have seen written about it except perhaps ‘‘Know you her secret none can utter?’’’

The quotation is the opening line of a poem called ‘Alma Mater’ by Arthur Quiller-Couch. Known as ‘Q’, he was the archetypal Oxford man of letters – who by Waugh’s time had, with great disloyalty, seated himself in the King Edward VII Chair of English Literature at Cambridge. A typical stanza from ‘Alma Mater’ reads:

Once, my dear – but the world was young then –

Magdalen elms and Trinity limes –

Lissom the blades and the backs that swung then,

Eight good men in the good old times –

Careless we, and the chorus flung then

Under St Mary’s chimes!

Though Evelyn was not the lissom type that might take to the river in a rowing eight, he shared Q’s rosy-tinted vision. Oxford was ‘mayonnaise and punts and cider cup all day long’. Charles Ryder’s voice is his own: ‘Oxford, in those days, was still a city of aquatint … her autumnal mists, her grey springtime, and the rare glory of her summer days … when the chestnut was in flower and the bells rang out high and clear over her gables and cupolas, exhaled the soft vapours of a thousand years of learning.’ Late in life, revising Brideshead for the last time, Waugh changed that last phrase to ‘exhaled the soft airs of centuries of youth’. Oxford ultimately stood for youth more than learning.

What would he have looked like to his fellow undergraduates? He was an attractive young man, short and slim with reddish, wavy hair, a sensuous mouth and a penetrating gaze. He had large hands, which he called craftsman hands. A wonderful hearty laugh, nearly an octave lower than his speaking voice. Those who knew him at this time testified to his peculiar charm, something that had not been nearly so apparent at Lancing. For some he was ‘faun-like’ – more an allusion to his light-footed energy than his diminutive stature. Despite the fierceness of his blue eyes and his slight swagger, there was an engaging air of vulnerability about him. Nevertheless, he could be impatient and cruel, especially to those less clever. He was not a kind young man, but he was generous and quick to see kindness in others.

For his first two terms he led a quiet and uneventful life. He claimed that he was content: ‘I have enough friends to keep me from being lonely and not enough to bother me,’ he wrote in a letter, adding that he did little work and dreamed a lot. But in other letters he lamented the lack of congenial friends. He complained of the ones he had met so far, ‘a gloomy scholar from some Grammar school who talked nothing, some aristocratic men who talked winter sports and motor cars’. The highlight of his first term was to buy finely bound editions of Rupert Brooke and A. E. Housman’s haunting homoerotic poetry collection A Shropshire Lad, volumes that he could ill afford. He reported the purchases with relish in letters to his school friend, Tom Driberg.

In his memoir of his early years, self-deprecatingly entitled A Little Learning, Waugh described the first part of his Oxford education as typical of a scholarship freshman from a minor public school. Subdued but happy, he purchased a cigarette box carved with the college arms, learned to smoke a pipe, got drunk for the first time, made a speech at the Union and did just enough work to scrape through his first year exams. ‘But all the time it seemed to me,’ he wrote, ‘that there was a quintessential Oxford which I knew and loved from afar and intended to find.’

He knew that he was in search of something, but he was not quite sure what it was.

In A Little Learning he quoted Q’s line about Oxford’s ‘secret none can utter’ once again. ‘It is not given to all her sons either to seek or find this secret,’ he commented, ‘but it was very near the surface in 1922.’ The clear implication is that he was on the brink of being let into the secret of the quintessential Oxford. At this point in his memoir he named one of his contemporaries: ‘Pembroke [College] harboured Hugh Lygon and certain other aristocratic refugees from the examination system.’ Pembroke was a college that had a reputation for welcoming the ‘cream’ of Oxford (rich and thick). Hugh was not the most intellectual of men, but after a period of study in Germany he had duly come up to Oxford. He would hardly have been turned away, given his pedigree.

Evelyn did not care in the least that the place was no meritocracy. Having won his scholarship to Hertford, he was determined to get through his three years with the minimum of work. Like many of his contemporaries, he subscribed to the notion that Oxford was a place ‘simply to grow up in’ rather than somewhere to gain an education or a step into a career path. More than anything, Oxford was the place where you met the friends that would be with you for life. Initially, it must have seemed to Evelyn that he was doomed to stay with the dull, middle-class friends of his first two terms. Glamorous aristocratic boys such as Hugh Lygon and Lord Elmley were as remote as Mars. They belonged to sets that seemed impossible to infiltrate, a world that was exclusive, elegant and composed almost entirely of Old Etonians.

In Oxford lore, 1922 and 1923 would come to be regarded as no ordinary years. When Evelyn came to write his own love poem to Oxford in Brideshead Revisited he was careful to be explicit that Charles Ryder was of this vintage. A revolution was afoot and two men were its instigators: Harold Acton and Brian Howard. Eton had already made them into legendary figures, thanks to the Candle. To begin with, Oxford regarded them as an odd couple: Harold with his tall stooping figure, peculiar gait and abnormally small head, Brian with his swarthy demeanour, slicked back hair, huge dark eyes, and pouting mouth. Flagrantly homosexual, eccentric, worldly and cosmopolitan: Oxford had seen nothing like them since the days of Oscar Wilde. Paradoxically, Acton and Howard themselves considered Wilde effete and second-rate: ‘Old Oscar screwed the last nail in the aesthete’s coffin’ was their view of the matter. They stood for a more robust aestheticism mingled with modernism. They read not Wilde and Swinburne, but Edith Sitwell, James Joyce and T. S. Eliot.

Acton’s mantra was plainly set out: ‘Now that the war was over, those who loved beauty had a mission, many missions. We should combat ugliness; we should create clarity where there was confusion; we should overcome mass indifference; and we should exterminate false prophets.’ In his memoirs, Acton described his group as ‘aesthetic hearties’: ‘There were no lilies and languors about us; on the whole we were pugnacious.’ They despised the very things of which they were so often accused: pretentiousness and affectation. As at Eton, Harold was the undisputed leader, on a mission to re-educate Oxford. But Brian was just as influential and it was sometimes hard to separate them. The two men were regarded as rivals, friends, enemies and ‘almost twins’.

Harold, to the amusement of his friends, stood on his balcony window with a megaphone, through which he recited poems (usually Eliot or Sitwell) to groups passing below in Christ Church Meadow. He painted his rooms in lemon and filled them with Victorian furniture, artificial flowers and wax fruit under bell jars. This love of Victoriana was a kind of retro kitsch, which almost began as a joke, a rebellion against classicism. These boys wanted modernism with an ironic twist.

News of the extraordinary pair spread like wildfire around drab post-war Oxford. Their highly distinctive turns of phrase were repeated at parties. ‘Your etchings are the messes of a miserable masturbator,’ Acton told one young man. Brian Howard remarked to a lovesick boy at a party: ‘My dear … I feel that your fly buttons will burst open any minute and a large pink dirigible emerge, dripping ballast at intervals.’

Most undergraduates wore three-piece broadcloth suits. Brian and Harold were noted for sartorial elegance that set them apart from the crowd. Their clothes were beautifully made, described by one fellow Old Etonian as ‘an intoxication’. They wore suits by Lesley & Roberts, cut in early Victorian style with high shoulders and big lapels. Their white double-breasted waistcoats were from Hawes & Curtis of Jermyn Street. They had monogrammed silk shirts, silver, mauve and pink trousers. Their casual wear included cashmere turtle-necked sweaters in bright colours, suede shoes, raspberry crepe-de-Chine shirts, green velvet trousers, and yellow hunting waistcoats. Harold wore a grey bowler, a trailing black coat and his infamous ‘Oxford bags’ (twenty-six inches wide at the knee and twenty-four at the ankle, covering the shoes).

Acton’s nomenclature for their set was deliberately provocative, since Oxford was traditionally divided between Aesthetes and Hearties. Henry Yorke offers a choice description of the braying hearties: ‘a rush of them through the cloisters, that awful screaming they affected when in motion imitating the cry when the fox is viewed, the sense curiously of remorse which comes over one who thinks he is to be hunted, the regret, despair and feeling sick the coward has.’ A scrum of drunken hearties from the rowing club ducked Harold Acton in his pyjamas in the Mercury Fountain in Christ Church’s Tom Quad. This is the origin of the incident in Brideshead where members of the notorious Bullingdon Club attempt to duck Anthony Blanche. On another occasion, thirty men – the equivalent of the first and the second rugby fifteens combined – assaulted Acton’s room. He recalled the incident: ‘I, tucked up in bed and contemplating the reflection of Luna on my walls, was immersed under showers of myriad particles of split glass, my hair powdered with glass dust and my possessions vitrified.’ Brian Howard received news of the attack from his mother, who heard it (at Edith Sitwell’s recitation of her poem Façade) from the mother of one of Harold’s assailants: ‘If I’d been there I’d have unloosed her corsets on the spot’ was his riposte.

Evelyn, feeling that something essential in Oxford was eluding him, did the minimum of academic work. He blamed his disillusion with academia on his bad relationship with his tutor, C. R. M. F. Cruttwell, who was also Dean of Hertford College. The bad feeling was mutual. Cruttwell disliked Evelyn, convinced that he was wasting his scholarship. He described his student as a ‘silly suburban sod with an inferiority complex and no palate’. Evelyn in return despised Cruttwell, describing him as ‘a wreck of the war’ who had ‘never cleaned himself of the muck of the trenches’.

In Evelyn’s third term he changed to a more spacious set of rooms on the ground floor of the front quad. This left him vulnerable to people dropping in to dump their bags or to cadge a drink and a cigarette. He decorated the rooms with Lovat Fraser prints and kept a human skull in a bowl, which he decorated with flowers. One night a group of ‘young bloods’ came into the quad drunk and looking for trouble. One of them leaned into Evelyn’s window and was violently sick.

Having failed to be invited to join any of the university’s famous drinking or dining clubs, Evelyn formed his own. He called it the ‘Hertford Underworld’. His friends would come to his rooms to drink sherry and eat bread and cheese. It all felt rather unglamorous.

His Oxford experience was transformed when he was befriended by the charming, though slightly mad, Terence Greenidge. It was Greenidge who was responsible for introducing him to a new circle of friends. Meeting him was the beginning of a sentimental education.

Greenidge’s habits included an obsession with tidiness. His pockets were often crammed with litter from the streets. In his person, by contrast, he was very untidy. He was a kleptomaniac, who filched any trifle that took his fancy: hairbrushes, keys, nail scissors, inkpots. He secreted his ill-gotten gains in orderly heaps behind books in the library. Evelyn was drawn to his zany humour and his child-like aura. Always in trouble with the college authorities, Greenidge loved practical jokes and declaimed Greek choruses loudly at night in the quad. He also invented nicknames that delighted Evelyn. Alec Waugh was ‘Baldhead who writes for the papers’, the night porter was ‘Midnight Badger’, another contemporary was ‘Philbrick the Flagellant’ (who on one occasion beat up Evelyn). Hugh Molson (Evelyn’s Lancing friend) was ‘Hotlunch’, since he often complained about the cold lunches.

Evelyn and Greenidge put about a rumour that Cruttwell was sexually attracted to dogs. They barked under his windows at night and bought a stuffed dog, which was put in the dean’s path as he walked home drunk after a college dinner. Greenidge developed a reputation as a dangerous influence. When Lord Beauchamp (‘no prude’, says Evelyn with typically mischievous understatement) found Greenidge in his elder son’s rooms, he took his boy down from the university for two terms, fearing that Elmley had got into a bad set.

Greenidge described Evelyn in his undergraduate days as having ‘the attractive appearance of a mischievous cherub’. He recalled him as a well-dressed figure, usually to be seen in a pale blue plus-four suit and carrying ‘a short stout stick which was almost like a cudgel’. He remembered that Evelyn’s ‘conversation, though emotional, always appeared reasonable, his assurance was remarkable, and his wit was remarkable’. The plus fours would become a trademark. Waistcoats were also favoured. Fellow Oxford undergraduate Peter Quennell remembered that the first time he met Evelyn, ‘he was small and neat, and dandified, wearing a bright yellow waistcoat’. There was a touch of Mr Toad about him.

Evelyn continued to be attracted to eccentric, anarchic characters. They brought out his own streak of zaniness. Greenidge later suffered from mental illness but nevertheless managed to hold down a job as a minor actor at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. He remembered Evelyn as slightly mad, but extremely kind and loyal. In later years, he lent Greenidge large sums of money, always sending it by return of post whenever he was asked for help. Evelyn was uninterested in money. Greenidge had ‘a feeling that he was aware unconsciously that his talent was – well – formidable. It is rather pleasant that to him who did not worry about it great wealth came.’

At a lecture given by G. K. Chesterton to a Catholic group, the Newman Society, Greenidge introduced Evelyn to Harold Acton. Evelyn and Acton became immediate and enduring friends. Acton began attending the Hertford Underworld in Evelyn’s rooms. Evelyn was convinced that the main reason for his appearance in such a humble setting was that he was infatuated with one of the Hertford men in the group. Refusing to drink beer and eat the plain fare, Acton would sip water and stare at the young Adonis. But in return he invited Evelyn to lunch and introduced him to his Eton friends, including Hugh Lygon.

Acton was now editing a new modernist literary magazine, a successor to the Eton Candle called the Oxford Broom. Waugh drew the cover for the second edition in spring 1923. Then he wrote a story for the third number, which was published in June 1923. Entitled ‘Antony, who sought things that were lost’, it concerns a beautiful young aristocrat, ‘born of a proud family’, who ‘seemed always to be seeking in the future for what had gone before’. He was perhaps the first fictional draft for the Sebastian type, created exactly at the time when Evelyn was beginning to be drawn to Hugh Lygon and his kind.

His Oxford life had truly begun.

Evelyn hero-worshipped Acton. He would eventually dedicate his first novel to him ‘in homage and affection’. They were an unlikely pair. Even Evelyn was puzzled as to what they had in common. Acton was worldly, sophisticated, cosmopolitan. Evelyn was self-confessedly ‘insular’: ‘At the age of nineteen I had never crossed the sea and knew no modern language.’ What drew them together, he said, was what he called gusto, a ‘zest for the variety and absurdity of life, a veneration of artists, a loathing of the bogus’. Acton was the leader and Evelyn the follower. Evelyn loved the slightly older man’s funniness, his cleverness, his eccentricity. ‘He loved to shock and then to conciliate with exaggerated politeness … he was himself shocked and censorious at any breach of his elaborate and idiosyncratic code of propriety.’

Harold Acton was equally enchanted. He described Evelyn as ‘an inseparable boon companion … I still see him as a prancing faun … wide apart eyes, always ready to be startled under raised eyebrows, the curved sensual lips, the hyacinthine locks of hair’. He detected something behind the shyness: ‘So demure and yet so wild.’ He loved the mischievous sparkle in his friend’s eyes, the capacity for joy, the jokes. Evelyn’s wit, charm and gift for irony compensated for the mood swings that Acton also observed: ‘Spontaneous, ebullient, vivacious, then silent, sullen, staring at the world with critical distaste … his apparent frivolity was the beginning of true wisdom.’ For Evelyn ‘a sense of the ludicrous’ was the essence of sanity.

Though intoxicated by Acton and the new set into which he was drawn, Evelyn was wary of Brian Howard, describing him as Lord Byron was famously described a century before: mad, bad and dangerous to know. Howard’s ‘ferocity of elegance’ seemed to belong to the age of Byron, not the present. Evelyn couldn’t quite cope with it. Or perhaps it was the sheer exhibitionism of Howard’s homosexuality that both fascinated and repelled him.

Harold Acton gave Evelyn an entry into the Hypocrites’ Club. There he discovered hard drinking and firm friendship: ‘it was the stamping ground of half my Oxford life and the source of friendships still warm today’. It was at the Hypocrites that he was introduced to Hugh Lygon and his elder brother Elmley.

The Hypocrites was one of many drinking clubs at the university – such clubs were necessary because undergraduates were banned from going into the city’s pubs, for fear of town versus gown fisticuffs or liaisons with unsuitable women. The most exclusive of the clubs was the famous Bullingdon, immortalised by Evelyn in his novel Decline and Fall, where it becomes the Bollinger Club, characterised by ‘the sound of the English county families baying for broken glass’. The Bullingdon was a top-secret (all male, of course) dining club, not strictly a drinking society. Then, as now, it drew its membership from the super rich. It was known then for champagne drinking, ritualised violence and a uniform that consisted of exquisite Oxford blue tailcoats offset with ivory silk lapel revers, brass monogrammed buttons, mustard waistcoat and sky blue bow tie. All members had to endure a humiliating initiation rite that included having their rooms trashed as champagne was binged upon and regurgitated. Freddy Smith, second Earl of Birkenhead (president of Pop at Eton, Christ Church man and future military colleague of Evelyn in Yugoslavia), captured the Bullingdon men with aplomb: ‘eldest sons from aristocratic families who drank champagne at breakfast and were often to be found flourishing hunting-whips and breaking windows in Peckwater Quad’.

Harold Acton was not the type (or the class) to have become a member of the Bullingdon. Brian Howard, on the other hand, being a huntsman as well as an aesthete, was once invited to one of their dinners, after which 256 panes of college glass were smashed. He followed up this adventure by spending, as he put it, ‘a tumultuous night between the sheets’ with a club member.

The Hypocrites’ Club did not have quite the same exclusivity, though it too was characterised by a love of fine dining and, most importantly, hard drinking. If the motto of the Bullingdon was an unequivocal ‘I love the sound of broken glass’, that of the Hypocrites was laced with neat irony: ‘water is best’. The watchwords were style and panache. Conversation turned on art and literature rather than deer-stalking and riding to hounds. The club was at this time in a state of transition. Its original members had been heavy drinking but somewhat sombre Rugbeians and Wykehamists (former pupils of Rugby and Winchester, the latter being generally regarded as the most academic of the great public schools). But as Evelyn arrived in Oxford it was in the process of ‘invasion and occupation by a group of wanton Etonians who brought it to speedy dissolution’. The Hypocrites’ Club was beginning to be associated with flamboyant dress and a manner that had the distinct smack of homosexuality. The name of the club came from the ancient Greek word for an actor: it was a place where you could pose and play roles. The president was Lord Elmley. As the sons of an earl, Elmley and Hugh were natural Bullingdon men. Their presence among the Hypocrites was intriguing and provocative.

‘At Oxford I was reborn into full youth,’ wrote Waugh apropos of his life once he had been initiated among the Hypocrites. He later denied that he had any ambitions to ingratiate himself with the wealthy or to ‘make influential friends who would prosper any future career’. He said that his interests were ‘as narrow as the ancient walls’. For Evelyn it was quite simple: he wanted to be loved and he wanted to live fully and freely – ‘I wanted to taste everything Oxford could offer and consume as much as I could hold.’

Gone were the days of bread, cheese and beer in the Hertford Underworld. Now it was abundant food and fine wines, claret followed by port. He quickly ran into debt and had to auction all his books.

In his capacity as club president, Elmley promulgated a rule that ‘Gentlemen may prance but not dance.’ Along with aestheticism and irony, a welcoming of overtly homosexual behaviour was one of the things that set the Hypocrites apart from the Bullingdon, let alone the rowing and rugger clubs.

The Hypocrites initiated Evelyn into the habit of hard drinking. Because of fear that American-style prohibition might be on the way to Britain, there was ‘an element of a Resistance group about the drunkards of the period’. The club premises – rooms above a bicycle shop – were described by one of Evelyn’s friends as a ‘noisy alcohol-soaked rat-warren by the river’. Evelyn remembered a Tudor half-timbered building with a steep and narrow staircase, smelling of onions and stewed meat. He said that the local police constable was usually to be found there, taking a break from his beat, standing in the kitchen, mug of beer in one hand and helmet in the other. The two large rooms beyond the kitchen were decorated with murals by Oliver Messel and Robert Byron. There was a large piano where members played jazz riffs or accompanied the singing of Victorian drawing-room ballads.

Though Evelyn portrayed the place as a den of iniquity, it was actually very civilised. Harold Acton said that there was always someone to talk to ‘with a congenial hobby or mania’, as if suggesting a tweedy discussion of stamp-collecting rather than a Bullingdon-style debauch. What Evelyn loved about the place was its conversation. He relished hearing Acton affect an Italian accent and say: ‘My dears, I want to go into the fields and slap raw meat with lilies.’

In his memoirs Evelyn gave a roll call of the names of famous people who were members of the club. The best and worst that the university had to offer were either members or guests. The club was beginning to get a reputation. Isis, the university newspaper, reported that its members were distinctly alarming on account of their dazzling intellectual catch-phrases and cultivated rudeness.

Evelyn’s new friends brought him into a circle that was altogether much grander than any he had hitherto known. He found himself among an extraordinary set of young men who would continue to make waves after they left Oxford. There were other pairs of brothers besides the aristocratic Lygons. First the Duggan boys, Alfred and Hubert. Alfred had the aura of a ‘full-blooded rake of the Restoration’ and his younger brother Hubert – Anthony Powell’s Eton messmate – was ‘a delicate dandy of the Regency’. Then there were the Plunket Greenes, David and Richard. Both were musical. David was a gentle giant who loved jazz. Many of these young men ended up as alcoholics or suicides (or both). But to young Evelyn they were glamour itself. He and most of his friends were often drunk, whereas Alfred Duggan was always drunk. The Duggans, stepsons of Lord Curzon, Chancellor of the University, had vast riches at their disposal.

Many members of the Hypocrites, including Evelyn, became members of another fraternity, The Railway Club – motto: ‘There is no smoke without fire.’ Its founder was John Sutro, a Trinity College undergraduate from a wealthy Jewish family. His home was where Evelyn first tasted plovers’ eggs. He became a true friend. Evelyn remembered his loyalty and hospitality, describing him as ‘above all humorous; a mimic of genius … he has never wearied of a friend or quarrelled with one’.

The Railway was so called because Sutro was an aficionado of nighttime journeys on steam trains. Club members would travel around the country, dining on the outward leg and sharing post-prandial drinks in the train bar on the return to Oxford. Dinner jackets were always worn. Hugh Lygon was a member. Even after Oxford, the club continued to hold dinners. Over time, the menus grew more and more elaborate, while, in order to accommodate them, the journeys became longer and more adventurous.