По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

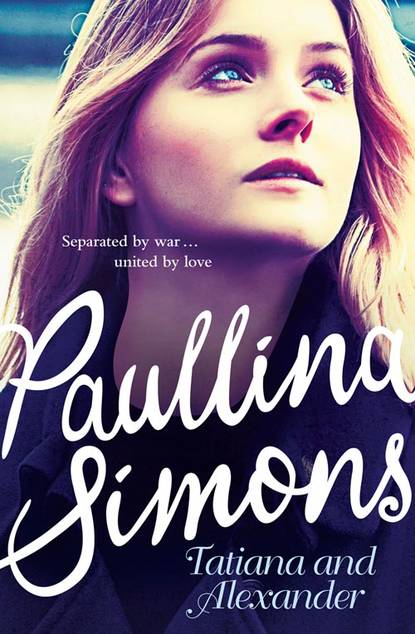

Tatiana and Alexander

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Alexander was silent. He did not want to side against his father.

“You see?” Jane exclaimed triumphantly. “Please, Harold. Soon it will be too late.”

“You’re talking rubbish. Too late for what?”

“Too late for Alexander,” Jane said brokenly, pale with despair. “For him, forget your pride for just one second. Before he has to register for the Red Army when he turns sixteen in May, before tragedy befalls us all, while he is still a U.S. citizen, send him back. He has not relinquished his rights to the United States of America. I will stay with you, I will live out my life with you—but—”

“No!” Harold exclaimed in an aghast voice. “Things didn’t turn out the way I had hoped, look, I’m sor—”

“Don’t be sorry for me, you bastard. Don’t be sorry for me—I lay down in this bed with you. I knew what I was doing. Be sorry for your son. What do you think will happen to him?”

Jane turned away from Harold.

Alexander turned away from his parents. He went to the window and looked outside. It was February and night.

Behind him, he heard his mother and father.

“Janie, come on, it’ll be all right. You’ll see. Alexander will be better off here eventually. Communism is the future of the world, you know this as well as I do. The wider the chasm between the rich and the poor in the world, the more essential communism is going to become. America is a lost cause. Who else is going to care about the common man, who else will protect his rights but the communist? We’re just living through the toughest part. But I have no doubt—communism is the future.”

“God!” Jane exclaimed. “When will you ever stop?”

“Can’t stop now,” he said. “We’re going to see this through to the end.”

“That’s right,” Jane said. “Marx himself wrote that capitalism produces above all its own gravediggers. Do you think that perhaps he wasn’t talking about capitalism?”

“Absolutely,” agreed Harold, while Alexander looked the other way. “The communists hate to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing conditions. The fall of capitalism is inevitable. The fall of selfishness, greed, individuality, personal attainment.”

“The fall of prosperity, comfort, humane living conditions, privacy, liberty,” said Jane, spitting the words out, as Alexander doggedly stared out the window. “The second America, Harold. The second fucking America.”

Without turning back, Alexander saw his father’s angry face and his mother’s despairing one, and he saw the gray room with the falling plaster, and the broken lock held together by tape, and he smelled the washroom from ten meters away, and he was silent.

Before the Soviet Union, the only world that had made sense to him was America, where his father could get up on the pulpit and preach the overthrow of the U.S. government, and the police that protected that government would come and remove his father from the pulpit and put him into a Boston cell to sleep off his insurrectionist zeal, and then in the next day or two they would let him out so he could recommence with renewed fervor preaching to the curious the lamentable deficiencies of 1920s America. And according to Harold there were plenty, though he himself admitted to Alexander that he could not for the life of him understand the immigrants who poured into New York and Boston, who lived in deplorable conditions working for pennies and put generations of Americans to shame because they lived in deplorable conditions and worked for pennies with such joy—a joy that was diminished only by the inability to bring more of their family members to the United States to live in deplorable conditions and work for pennies.

Harold Barrington could preach revolution in America and that made perfect sense to Alexander, because he read John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty and John Stuart Mill told him that liberty didn’t mean doing what you damn well pleased, it meant saying what you damn well pleased. His father was upholding Mill in the greatest tradition of American democracy; what was so wrong with that?

What didn’t make sense to him when he had arrived in Moscow was Moscow. As the years passed, Moscow made only less and less sense to him; the privation, the senselessness, the discomfort encroached upon his youthful spirit. He had stopped holding his father’s hand on the way to Thursday meetings; what he keenly felt absent from his own hand, however, was an orange in the winter.

Hailing Russia as the “second America,” Comrade Stalin proclaimed that in a few years the Soviet Union would have as many railroads, as many paved roads, as many single family houses, as the United States. He said that America had not industrialized as fast as the USSR was industrializing because capitalism made progress chaotic, whereas socialism spearheaded progress on all fronts. The U.S. was suffering thirty-five per cent unemployment, unlike the Soviet Union which had near full employment. The Soviets were all working—proof of their superiority—while the Americans were succumbing to the welfare state because there were no jobs. That was clear, nothing confusing about that. Then why was the sense of malaise so pervasive?

But Alexander’s feelings of confusion and malaise were peripheral. What wasn’t peripheral was youth. And he was young, even in Moscow.

He turned back to his mother, handing her a napkin to wipe her face while wiping his own with his sleeve. Before walking out and leaving them to their misery, Alexander said to his father, “Don’t listen to her. I will not go to America alone. My future is here, for better or worse.” He came a little closer. “But don’t hit my mother again.” Alexander was already several inches taller than Harold. “If you hit her again, you’ll have to deal with me.”

A week later Harold was removed from his job as a printer because as the new laws would have it, foreigners were no longer allowed to operate printing machinery, no matter how proficient they were and how loyal to the Soviet state. Apparently there was too much opportunity for sabotage, for printing false papers, false affidavits, false documents, false news information, and for disseminating lies to subvert the Soviet cause. Many foreigners had been caught doing just that and then distributing their malicious propaganda to hard-working Soviet citizens. So no more printing for Harold.

He was redeployed to a tool-making factory, melting metal into screw-drivers and ratchets.

That job lasted a few weeks. Apparently it also wasn’t safe. Foreigners had been caught making knives and weapons for themselves instead of tools for the Soviet state.

He was then employed as a shoemaker, which amused Alexander (“Dad, what do you know about making shoes?”).

That job lasted only a few days. “What? Shoe-making isn’t safe either?” Alexander asked.

Apparently it wasn’t. Foreigners had been known to make galoshes and mountain boots for good Soviet citizens to escape through marshes and through mountains.

A somber Harold came home one April evening in 1935 and instead of cooking (it was Harold who cooked dinner for his family now), sat down heavily at the table and said that a Party Obkom man had come to see him at the school where he was working as a floor sweeper and asked him to find a new place to live. “They want us to find our own rooms. Be a little more independent.” He shrugged. “It’s only right. We’ve had it relatively easy the last four years. We need to give something back to the state.” He paused and lit a cigarette.

Alexander saw his father glance at him furtively. He coughed and said, “Well, Nikita has disappeared. Maybe we can take his bathtub.”

There was no room for the Barringtons in all of Moscow. After a month of looking, Harold came home from work and said, “Listen, the Obkom man came to see me again. We can’t stay here. We have to move.”

“By when?” Jane exclaimed.

“Two days from now. They want us out.”

“But we have nowhere to go!”

Harold sighed. “They offered me a transfer to Leningrad. There is more work—an industrial plant, a carpentry plant, an electricity plant.”

“What, no electricity plants in Moscow, Dad?”

Harold ignored Alexander. “We’ll go there. There’ll be more rooms available. You’ll see. Janie, you’ll get a job at the Leningrad public library.”

“Leningrad?” Alexander exclaimed. “Dad, I’m not leaving Moscow. I got friends here, school. Please.”

“Alexander, you’ll start a new school. Make new friends. We have no choice.”

“Yes,” Alexander said loudly. “But once we had a choice, didn’t we?”

“Alexander! You will not raise your voice to me,” Harold said. “Do you hear?”

“Loud and clear!” shouted Alexander. “I’m not going. Do you hear?”

Harold jumped up. Jane jumped up. Alexander jumped up.

Jane said, “No, stop it, stop it, you two!”

“You will not speak to me this way,” Harold said. “We are moving, and I don’t want to talk another minute about it.”

He turned to his wife and said, “Oh, and one more thing.” Sheepishly, he coughed. “They want us to change our name. To something more Russian.”

Alexander scoffed. “Why now? Why after all these years?”

“Because!” Harold shouted, losing control. “They want us to show our allegiance! You’re going to be sixteen next month. You’re going to register for the Red Army. You need a Russian name. The fewer questions, the better. We need to be Russians now. It will be easier for us.” He lowered his gaze.

“God, Dad,” Alexander exclaimed. “Will this ever stop? We can’t even keep our name anymore? It’s not enough to kick us out of our home, to move us to another city? We need to lose our name, too? What else have we got?”

“We are doing the right thing. Our name is an American name. We should have changed it long ago.”