По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

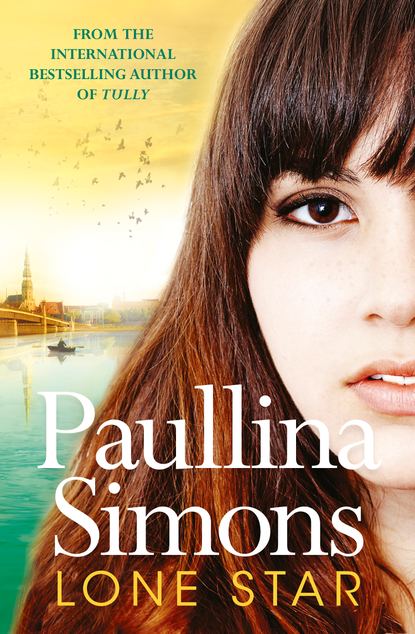

Lone Star

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Do you only want to hear the cathedral bells?”

Um, yes?

“What about examining for five minutes your place in the world, what it means to be alive? What it means to be dead?”

“Enough, Mom,” Jimmy said in a voice more exasperated and tired than Chloe’s. “Unlike some others we won’t mention, Chloe gets it.” Jimmy turned to his daughter. “It’s not ideal, Chloe-bear,” he said, putting his arm around her. “It’s called life. You endure a lot of stuff you don’t care about, but then, if you’re lucky, you get what you want.” Jimmy’s eyes caught Lang’s for a glimpse.

Chloe took a few minutes to compose herself before she spoke. “Moody, Mom, Dad, do you guys have any idea how far Riga is from Barcelona?”

Moody smiled with a full set of dentures. “Yes,” she said. “A train ride away across Europe, just like they did it in the war days.”

12 (#ulink_c35cbb52-4cf2-5e00-96ca-77a9e5757c18)

Peacocks (#ulink_c35cbb52-4cf2-5e00-96ca-77a9e5757c18)

THAT NIGHT UP IN THE ATTIC LANG SAT ON CHLOE’S BED. “Your father doesn’t want you to be upset. He thinks we were too hard on you. Some police chief! He’s gone soft in the head, I tell you. The fight has gone out of him.”

“I wonder why,” Chloe muttered. Lang said nothing.

“We don’t want you to be disappointed,” she said when she spoke again. “Dad and I don’t fully understand why you want to go, but then we’re not meant to, are we? I almost wonder if you yourself know. And that’s all right too. If you think you need to go to Barcelona to discover what you want and who you are, then who are your father and I to stand in your way? Your acceptance of Moody’s generous terms is wise. I know you’re worried about your friends not wanting to go to Latvia, but I think they’re going to surprise you. Besides, what choice do you have, really?”

“Not go?”

Lang nodded. “That will make your father happy,” she said. “In any case, everyone agrees the boys should go with you. Burt, Janice, Moody. They’ll keep you safe. Your father and I won’t argue this anymore. If you must go, then better with them. Soon you’ll be far away, and they’ll still be here saving up for that junk-hauling truck they won’t be able to afford because they’ve spent the summer frittering away their money in Barcelona with you.”

“You mean in Poland with me. In Latvia with me. Trudging through graveyards and death museums. And orphanages. What fun.”

Lang remained unfazed. “Europe is your parting gift to your friends. Now you can say goodbye to them the way you’re meant to. Abroad. And I hope when you come back, you’ll see one or two obvious things in a different way. Though I told Moody and your father, I wouldn’t count on self-discovery. I barely count on you coming back in one piece.”

“Nice, Mom.”

Lang patted the pink quilt above Chloe’s leg. “This is our gift to you, letting you go. Your dad and I are proud of you. You’ve been a good girl. We wanted to reward you for not disappointing us the way other parents have been disappointed.”

“Like Terri?”

“Not Terri. I think she’s rather fond of her daughter. And Terri works the hardest in that family. That’s why she doesn’t give a damn about the raccoons and dinner and Hannah’s homework. When you have to care desperately about bringing home the bacon, you’re hardly going to be bothered about who cooks it or what species eat it.”

“Who do you mean, then? Mason and Blake? But you love Janice.”

“There you go again, putting words in our mouths and feelings into our hearts. I didn’t say Janice. I don’t mean anybody in particular. I’m just saying. We thank you for not letting us down.”

“Not letting you down how? By not dying?” Chloe was disappointed in herself. With her mother, and only with her mother (and maybe a little bit with Blake), she sometimes had trouble hiding her tortured heart.

A composed Lang said nothing.

For a few minutes, neither of them spoke.

“Just stay safe, all right?” Lang said quietly. “As safe as you can.”

“Mom, why do you want me to find you a strange boy?” Chloe whispered.

“Not strange,” Lang said. “Just someone who might need a little help. Someone you think your father and I might like. We’re not adopting him, Chloe. We’re sponsoring him. What are you worried about?”

“I’m not worried.”

Lang got up. “In this one way I echo Flannery O’Connor,” she said. “For the last eighteen years, my avocation has been raising peacocks. This requires everything of the peacocks and very little of me. Time is always at hand. Especially now that the last surviving peacock is leaving.”

The conversation was over. Lang smoothed out Chloe’s blanket and bent down to kiss her head. “How was the cemetery?”

“Fine. Moody insisted on putting my flowers on Uncle Kenny’s grave.”

Lang sighed as she took the railing to descend the steep attic stairs. “Why not? I do.”

13 (#ulink_3913f778-fcc4-5c6f-a55c-897d0a94ac50)

Uncle Kenny from Kilkenny (#ulink_3913f778-fcc4-5c6f-a55c-897d0a94ac50)

WHEN CHLOE WAS ELEVEN HER UNCLE KENNY DIED. He was a wild one, lived small, died small. He was cremated and a portion of his ashes were interred in Fryeburg’s rural cemetery, while the rest was flown to Kilkenny to be buried in the family plot next to Lochlan. Chloe’s parents flew to Ireland for his burial. Chloe got excited. Then she found out she wasn’t going.

They were gone a month.

“Must have been some funeral,” she said when her parents returned, all flushed and refreshed, as if they’d been on a honeymoon. They showed her photos of Dublin and Limerick, of glens and castle ruins, of moors and churches and pubs with names like the Hazy Peacock and the Rusty Swan. They began inexplicably to refer to the time away as a “trip of a lifetime.”

Chloe didn’t know what that meant, but she did internalize it.

Seven years later no one spoke of that trip of a lifetime, or of Kenny, or Kilkenny, or glens, or moors. Most of the pictures of Ireland had been taken off the walls of their wood cabin and stored in a box in the shed her father had built for the specific purpose of storing boxes with photos of Ireland in it, and of other mementos. One black and white Castlecomer dell remained in a frame in the hall.

A colossal vat of frightful things was stirred up by Kenny Devine’s vagrant life and subsequent (or consequent?) demise.

The Chevy truck he crashed his speeding swerving rattletrap into belonged to Burt Haul.

On the way home from work, Burt had stopped at Brucie’s Diner to pick up some meatloaf on Monday special. It was eight in the evening in July, not yet dark. It was warm, glorious, chirping.

Burt survived because his truck, built like a Humvee, had been in second gear. The same could not be said of Kenny or his Dodge Charger. Eyewitnesses, unreliable but myriad, clocked his miles per hour at somewhere between seventy and a hundred and twenty. He had no chance.

Burt lived, but barely. He suffered three broken vertebrae, a punctured lung, and five broken ribs. His kneecap, hip and femur were crushed almost beyond repair. It was upon visiting Burt in the convalescent facility that Moody first noted how blessed were those who could push around their own wheelchairs. Burt couldn’t.

His livelihood depended on his truck and his able body. When he wasn’t driving the school bus, he was a handyman. After four months in recovery, he found himself on a disability pension, still unable to walk. Janice Haul got a job at the attendance office at Brownfield Elementary School, but it barely paid half the bills. Little by little Burt improved, but was never the same. He couldn’t sit behind the wheel of a bus anymore, his fused and compressed vertebrae barking so loud they required handfuls of Oxycontin to quieten, and how well could anyone drive a school bus numbed up on Oxy?

Until Burt got well enough to return to work, he was replaced by a Brian Hansen, a recent Vermont transplant, and apparently an excellent driver.

Jimmy Devine’s animosity toward his brother, whose reckless existence had set into motion the spinning wheels of fate, was so violent that it ate apart the bond with his own family. He blamed Moody for never reining Kenny in, for indulging him, spoiling him, coddling him, paying his tickets, his suspended license fees, his legal bills, bailing him out of jail, buying him new wheels, allowing him to live in her basement and to drink her liquor. “Not just a good man’s back, but a whole family has been shattered, all because you could never say no to your firstborn son,” was one of the accusations Jimmy hurled at his mother, way back when. Burt and Jimmy and their families had been close before the accident, then less so, and then hardly at all. Burt blamed Jimmy for his ruined life, for knowing that Kenny should’ve never been allowed behind the wheel and yet doing nothing. “How much more could I do?” Jimmy argued in his defense. “Kenny’s license had been permanently suspended!”

And then, three years later, after another tragedy, Jimmy blamed not only Kenny for all the misfortune, but also Burt for not being man enough to get up every morning and drive the bus. It didn’t matter to Jimmy the pain Burt was in. Living three houses apart, the Hauls and the Devines stayed barely civil, even though Lang kept pointing out in feeble attempts to effect a truce between the men that Burt had done nothing wrong. “It’s not his fault he has a weak back, Jimmy.”

“Nothing wrong,” Jimmy said, “except stroll out of Brucie’s Diner with his arms full of meatloaf at precisely and absolutely the worst moment. Nothing wrong except not go to work, and ruin everybody’s fucking life.”

“He’s suffering too, Jimmy.”