По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

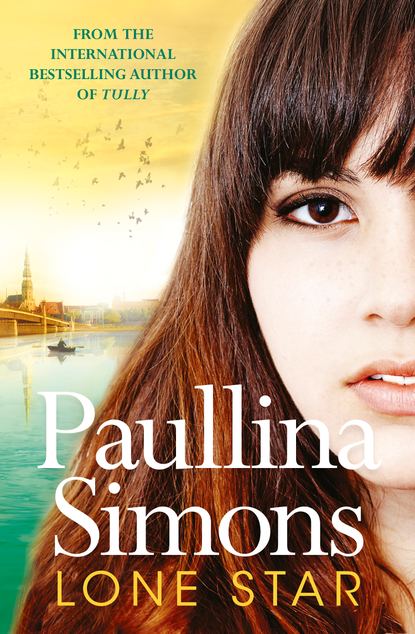

Lone Star

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

When Chloe was eleven, her parents had gone to Ireland without her. They said it was for a funeral. Pfft. Their trip formed the foundation of much, if not all, of the resentment of Chloe’s teenage years. A blown-up photo in a heavy gold leaf frame of the Castlecomer glens hung prominently in the hallway.

Lang continued to stare calmly at Chloe.

“You don’t need Kilkenny to write a story,” Lang said. “There are other things. Or, you make it up. That’s why they call it fiction.”

“Make it up from what? I’m going to make up a story about something so dramatic that it will win first prize?”

“Why not? Blake is.”

How did her mom know this!

“I’ve seen nothing. But Blake has seen rats and—” She stopped herself from saying used condoms.

“You have an imagination, don’t you?”

“No, none. I need a story, Mom. Not musings about what it’s like to live on a puddle lake in Maine.”

“Puddle lake? Have you glimpsed the stunning beauty outside your own windows?”

In the afternoons, the glistening lake, blooming willows and birches trimming the shoreline, the railroad rising on the embankment did occasionally shine with the scarlet colors of life. That wasn’t the point.

“I can’t write about skiing or bowling, or learning to drive,” Chloe continued. “I need something substantial. And I have nothing.” Why couldn’t she talk about herself without allowing a whiff of self-pity to waft through her smallest words? The one ashen tragedy in their life she could never write about. And Lang knew that. So why push it? Besides, her mother had once informed her that the Devine women were too short to be tragic figures. “We can be stoics, but not tragics,” Lang had said a few years ago, when it seemed to everyone else that the very opposite was the only thing true. “Make it up, darling,” Lang repeated, unperturbed by her daughter’s tone. “You’re a very good writer.”

“Mom, I don’t want to be a writer.”

“Neither does Blake. Yet look at him.”

Chloe watched her mother walk to the printer in the computer room behind the sofa and peel off several sheets of paper. Lang slapped the rules of entry for the Acadia contest on the table.

“You have five months to come up with a story and write it. It must be original. It must be fiction. And after it wins, it will be published by the University of Maine Press. Properly published! In book form and everything. That’s very exciting, isn’t it?”

“Did you not hear me?”

“No. By the way, I got you the pens you wanted.” Lang produced three packages of blue pens, gel, ballpoint, and fountain, and laid them in front of Chloe.

“I also took the liberty of getting you a notebook. Several different kinds to choose from. I thought you might need one if you’re going to write a story that’s going to win first prize. The Moleskine is very good. Has soft paper. But you try them all.”

Chloe stared at the pens, at the four notebooks. Had she actually mentioned that she needed a pen? One blue pen!

“Mom, listen to me.”

Lang sat down, elbows on the table, staring at Chloe with complete attention. She looked so pleased to be told to do what she had already been doing.

“I want to write something, I do. I just don’t think I have … look, here’s what we were thinking.”

“Who’s we?”

“The four of us.”

“The four of you were thinking all at once?”

“Well, discussing.”

“That’s better. It’s always good to be precise if you’re thinking of becoming a writer.”

“Which I’m not, so.”

“What are you four up to now? Let’s hear it.”

“We’re thinking of going to Europe.”

Lang stayed neutral. She didn’t blanch, she barely blinked. No, she did blink. Slowly, steadily, as if she was about to say …

“Are you crazy?”

There it was. “First listen, then judge. Can you do that?”

“No.”

“Mom. You just said you wanted me to write.”

“You have to go to Europe to write? Did Flannery O’Connor go to Europe? Did Eudora Welty? Did Truman Capote?”

“Actually, he did, yes.”

“When he wrote Other Voices, Other Rooms, his first novel, he’d been to Europe?”

“I don’t know. We’re getting off topic, Mom.”

“Au contraire. We are very much on topic.”

“Mason and Blake need to do research.”

“So they’re going to Europe?”

Chloe made a real effort not to facepalm, a real, true, Herculean, McDonald’s supersize-sandwich effort not to facepalm, because there were few things her mother hated more than this brazen gesture of exasperation and frustration.

“Hannah and I have been talking about the trip for a while.”

“I thought you just said you wanted to go for Blake and Mason? Make up your mind, child. Either you thought of it on the railroad tracks, or you’ve been planning it for years.”

“How do you know we were on the tracks?”

“I saw you.” Lang pointed out the window. “Right across the lake.”

Both things were true. Chloe and Hannah had been dreaming of going for years, but Blake and Mason just thought of it today. Lang sat and watched her daughter like a bird watching the world. One never knew what the Langbird was thinking until she sang.

“Isn’t going away to college enough for you?” Lang said quietly.