По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

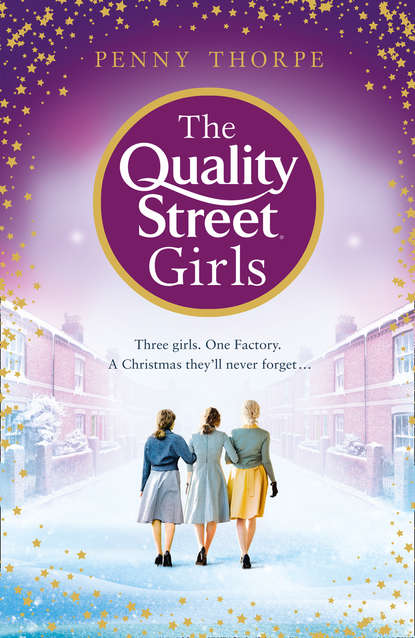

The Quality Street Girls

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Toffee Town: The sweet heart of Halifax (#litres_trial_promo)

Q&A with Penny Thorpe (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ua99d1feb-5903-5249-a8ee-8159066b0299)

It was late, and the Baxter’s store on the corner at Stump Cross was closed, but the lights in the main window illuminated a sparkling display of Mackintosh’s Quality Street; the latest success from the sprawling factory they called Toffee Town. As Reenie rode her nag closer she could see that someone had taken the coloured cellophane wrappers from the chocolates and taped them between black sugar paper to make little stained glass windows. Between the tins and tubs and cartons were homemade tree baubles; an ingenious mixture of ping-pong balls, cellophane wrappers, glue and thread.

While there were plenty of other confectionery assortments that Baxter’s could have chosen to feature, Reenie couldn’t imagine they’d have had much luck making a stained glass window out of O’Neil’s wrappers. Besides, Quality Street was the best, everyone knew it; plenty of girls from Reenie’s school had left to work in Sharpe’s or O’Neil’s factories, but it was the really lucky ones that went to work at Mackintosh’s.

Reenie’s enormous, ungainly old horse shuffled closer to try to nose the glass, the explosion of colour bursting forth from the opened tins on display had caught his eye and was drawing his curious nature to the window. Reenie didn’t blame him; it was a beautiful sight and he deserved a treat when he was being so good about coming out after putting in a day’s work in the top field. She had a great deal of affection for the old family horse, and she liked spoiling him when she got the chance, so she let him dawdle a while longer.

Reenie gazed at the window display, and dreamed of growing up to be the kind of fine lady that bought Quality Street, and had a gardener, and got driven around in an automobile. For the moment she would have to be content with being a farmer’s daughter who had a vegetable patch and occasional use of her family’s peculiarly ugly horse. Fortunately for Reenie, she found it easy to be content with her lot, she was an easily contented girl. As long as she didn’t have to go into service she was happy.

‘Come on, Ruffian. We’ve got a way to go yet.’ Ruffian reluctantly allowed Reenie to steer him away from the bright lights, and continued up through the ever steeper streets of Halifax, over quiet cobbles she knew well. The night was cold for October, but she knew she had to ride out to get her father nonetheless.

Reenie didn’t mind; Ruffian was technically her father’s horse, and most fathers would not allow their daughter freedom of the valley with it, so she supposed she ought to feel pretty grateful. And it wasn’t as though she had to come out to get her father very often, she thought to herself. He only got this blotto once a year when the Ale Taster’s Society hired out the old oak room and had their ‘do’, apart from that she thought he was pretty good really. He was very probably the best dad.

Reenie’s thoughts kept drifting back to the sandwich that was waiting in her pocket, wrapped in waxed paper and bound up with a piece of twine. The sandwich contained a slice of tinned tongue and some mustard-pickled-cauliflower that her mother made for Reenie to give to her father to eat on his way back. Reenie’s stomach rumbled and she was tempted to take a bite out of it before she got to the pub, even though she’d had her tea. Her mother frequently told her that she was lucky to live on a farm where there was no shortage of food, but Reenie pointed out that there was no shortage of the same food: mutton, ewe’s milk cheese, ewe’s milk butter, ewe’s milk curd tart, and ewe’s milk. She rode in the dark past the Borough Market, there was a clamour outside The Old Cock and Oak. As she approached, Reenie didn’t like the look of what she saw. Ahead of her, she could see brass buttons glinting in the old-fashioned gaslight from the pub, and the tell-tale contours of Salvation Army hats and cloaks. It was going to be another one of those nights.

Reenie knew before she’d even rounded the corner that this was not the regular Salvation Army, they would be off doing something useful somewhere involving soup and blankets. This was a Salvation Army splinter group, who the rest of the Salvation Army considered to be nothing but trouble. Reenie tried to feel friendly towards them as she wasn’t in a hurry, but she did wonder privately why they didn’t just go to the cinema when they got time off like everyone else.

‘Think of your wives! Think of your children!’ Reenie couldn’t tell where in the throng of ardent believers the call was coming from, but she knew that they wouldn’t be popular with the pub regulars. There were several other pubs along Market Street, but the faithful had chosen to cram into the courtyard of The Old Cock and Oak to protest against the annual meeting of the Worshipful Company of Ale Tasters. Reenie couldn’t see what they were so fussed about, but this wasn’t anything new.

Reenie decided not to dismount this time and walked old Ruffian as close to the pub door as she could, keeping a loose, but expert grasp on the fraying rope that served as Ruffian’s bridle. ‘Comin’ through, ‘scuse me, if you’d let me pass, please.’ As the ramshackle old horse nosed its way through the faithful, the crowd parted, some out of courtesy but others to avoid being stamped on by a mud-caked hoof, or bitten by an almost toothless mouth. Ruffian may not have had the aristocratic pedigree, but like his rider, he encouraged good etiquette in his own way. Reenie was close enough now to see a few faces she knew guarding the doorway; exasperated men waiting for the do-gooders to move on, their arms folded. ‘Is me dad in there still?’

‘Now then, Queenie Reenie, what’s this you comin’ in on a noble steed with your uniformed retinue.’ Fred Rastrick gave her a wicked grin as they both ignored the small, rogue faction of the otherwise helpful Halifax branch of the Salvation Army.

‘Don’t be daft, Fred, you know full well they’re nowt to do wi’ me. Now fetch us me dad, would ya’? It’s too cold for him to walk home, he’ll end up dead in a ditch. Go tell him I’m here and I’m not stopping out half the night so he has to be quick.’

‘Young lady! Young lady, how old are you?’ Reenie recognised the castigating voice of Gwendoline Vance, self-appointed leader of this band of Salvation Army members who’d taken it upon themselves to object to most things that went on in Halifax, including the Ale Tasters annual ‘do’. Reenie could have mistaken the woman’s face in the dark, even this close up, but there was no mistaking the way she was harping on.

‘What’s it to you?’ Reenie was not in a mood to be cross-examined by strangers, especially those in thrall to teetotalism.

‘Shouldn’t you be at school?’

‘Well, not just now as it’s half past ten at night.’

‘Well I meant in the morning, shouldn’t you be at home in bed by now so that you can go to school in the morning?’

‘No, and I’ll tell you for why. Firstly, I’m fifteen and I finished school at Easter; secondly, some of us would rather be spending our time helping our families than wasting it on enterprises that won’t get anyone anywhere; and thirdly (and forgive me if I think this is the most important), because today is a Friday, and when I were at school they taught me that the day that comes after Friday is Saturday, and that, madam, is when the school is closed. Now if you’ve quite finished, I want me’ dad. Fred!’ Reenie had to call out because Fred had disappeared further inside the pub. The Salvation Army devotee blanched and choked on her words. Reenie ignored her and turned her eyes to the doorway of The Old Cock and Oak.

‘He’s here, Reenie,’ Fred reappeared, ‘but he can’t walk.’

‘Well then tell him he doesn’t have to. I’m waiting with the ’orse.’

‘No, I mean he can’t walk. He’s blotto; out cold.’

‘Oh, good grief. Well, can someone drag him to the door, I don’t want to have to get off the horse or I’ll be here ‘til Monday.’

‘I’ll have a go.’ Fred turned to go back inside. ‘But he’s not as light as he used to be.’

‘Reenee,’ the do-gooder emphasised the Halifax pronunciation, ree-knee, and tried to assume an expression that was both patronising and penitent for her earlier mistake, ‘may I call you Reenie?’

‘No, you may not. Unless you’re gonna help with m’ dad.’

‘We’d be very, very glad to help with your father; it must be terribly hard on you and your family. Do you think you could bring him with you on Sunday to—’

‘No, I meant help lift him on the ’orse. Good grief, woman, are you daft? Fred! How’s he looking?’

‘Nearly there,’ Fred called out through gritted teeth as he attempted to pull the dead weight of Mr Calder out to his horse and daughter, then turned to a fellow drinker ‘Bert, can you give me an ‘and throwin’ him over Ruffian?’

Bert held up a hand and said, before darting back into the pub, ‘You wait right there; I think I know just the lad for this.’ Bert brought out a bemused-looking young man who Reenie didn’t recognise, slapping him on the shoulder with friendly camaraderie and pushing him in the direction of the horse. He didn’t have the slicked hair with razored back and sides that the other lads round here had. His hair wasn’t darkened by Brylcreem; instead, he had fine, golden toffee coloured hair that fell over his left eye and gave him away as a toff. Straight teeth, straight hair, straight nose, and a smarter suit of clothes than anyone else there; to Reenie, he looked hopelessly out of place among the factory workers and farm hands. It made her like him instantly for joining in with people who weren’t like him. She might not have a lot in common with this posh-looking lad, but there was one thing; he looked like the type who would make friends with anyone.

‘Reenie, Peter; Peter, Reenie.’ Bert skimmed over the necessary introductions. ‘We need to get Reenie’s dad here over the ’orse.’

Peter smiled and nodded, and with what seemed like almost no effort at all, he gathered Reenie’s father up and launched him in front of where Reenie sat, with his arms and legs dangling over the horse’s withers on either side. The landing must have been a rough one for Mr Calder because, though unconscious, he still managed to vomit onto the military-style black boots of the nearest Moral League man.

The sudden eruption caused a shriek from the group’s ringleader who turned to Reenie, ‘Oh you poor child. You shouldn’t have to see such things at your tender age.’

‘Oh gerr’over yourself, woman. Everyone’s dad drinks.’ Reenie bent over to check on her father because although she was confident that he’d be alright, she thought it was as well to make sure. Her shoulder-length red hair dangled down the horse’s side as she dropped her head level with her father’s, reassured by his loud snore; silly old thing, what was he like? Her mother would laugh at him come the morning. Reenie looked up to thank the young man, but to her disappointment, he’d already gone. She had wanted to tell him that her father wasn’t usually like this, and not to mind the Sally Army crowd because they weren’t bad as all that if you weren’t in a hurry to get anywhere. She had wanted to say so many things to him, but she supposed it was better she get a move on and take her father home to his bed. It didn’t occur to her that the young man had gone indoors to fetch his coat and hat so he could offer to walk her home like a gentleman.

Reenie pulled on Ruffian’s make-shift bridle and began to lead the horse away, then thought better of it and stopped to call over her shoulder ‘and my friend Betsy Newman’s in the Salvation Army and she says you six are pariahs! Go and help ‘em with the cleaning rota like they’ve told ya’, and stop botherin’ folks who’ve had an ‘arder week at work than you’ve ever known!’

Ruffian snorted, as if in agreement, and guided his mistress home.