По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

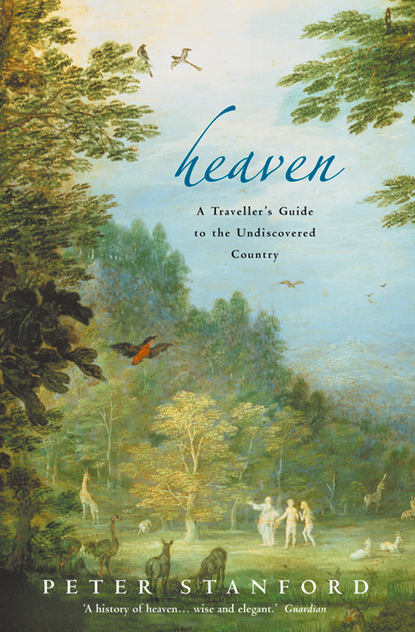

Heaven: A Traveller’s Guide to the Undiscovered Country

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Works (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS (#ulink_810c7408-24b4-5d3c-8e7d-678b53f01537)

Ascent of the Prophet Muhammad to Heaven by Aqa Mirak, 16th century.

© British Library/Bridgeman Art Library

Saint Augustine of Hippo. © Mary Evans Picture Library

Saint Hildegard. © Mary Evans Picture Library

Thomas Aquinas. © Mary Evans Picture Library

Chartres Cathedral, West side. © The Bridgeman Art Library

Land of Cockaigne by Pieter Brueghel. Alte Pinakothek, Munich. © TheBridgeman Art Library

Detail from The Damned by Luca Signorelli. © Scala

Dante portrait. © Scala

Ascent into the Empyrean by Hieronymus Bosch. Palazzo Ducale, Venice. © The Bridgeman Art Library

Dante and Beatrice, from Dante’s Divine Comedy, 1480, by Sandro Botticelli. © Bibliotheque Nationale/The Bridgeman Art Library

Emmanuel Swedenborg. © Mary Evans Picture Library

Cities in the Spirit World, 18th century by Emmanuel Swedenborg. Reproduced courtesy of The Swedenborg Society

The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, As a New Heaven is Begun, c. 1790, by William Blake. © The Bridgeman Art Library

Last Judgement by William Blake. © A.C. Cooper/The National TrustPhotographic Library

The Gates Ajar

Spiritualism photo

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Houdini. © Mary Evans Picture Library

The Resurrection: Cookham, 1924–7 by Sir Stanley Spencer. © Tate, London 2002

Illustration from The Last Battle by C.S. Lewis. © Pauline Baynes

Buddhist temple. © Ian Cumming/Tibet Images

INTRODUCTION (#ulink_544c84a0-9e50-586d-bb41-ce47e540af1b)

It is five in the morning and my five-month-old baby daughter, already settled into a pattern as an inveterate dawn riser, is shifting around in my arms, her eyes wide open, her back arching, and looking every inch a miniature version of my own mother. It is not so much the composition and arrangement of her features that bridges the generations, as a particular grimace of steely resolution that she makes, and the look she sometimes gives, with eyes guarded and slightly nervous, as she weighs you up before volunteering a broad but bashful smile. In these moments, the coincidence of her birth and my mother’s death within twelve months of each other makes me believe, without a shadow of a doubt, in reincarnation.

Bleary-eyed through lack of sleep, I see such a familiar expression that unthinkingly I latch on to it. For an instant I am as true a believer in reincarnation as if I were kneeling in saffron-coloured robes in a temple in the East: for, despite however many rules of science it violates, it seems so obvious that some essence of the life that is now over has been reborn in the new life in front of me. I even convince myself that it’s more than just the looks: they seem to share the same spirit – determined, unswerving, but cautious. As I slip back into a half-slumber, my daughter is distracted by an old watch strap, which she sucks and stretches. I add a few Christian ingredients to my Buddhist brew and fondly conjure up a scene in that mythical white tunnel which, in the standard church imagery of heaven, links this world to the next. There is, I imagine, a halfway point where those going back to the pavilion pass those going out to the crease. My mother and my daughter are both there, frozen in time, suddenly alone and utterly absorbed in each other. In my dream both can walk, though for the last twenty-five years of her life my mother was a wheelchair user. They embrace, and, as they take their leave to go in opposite directions, my mother kisses my daughter gently and hands over a parcel of her own characteristics, her legacy to the grand-daughter whom she will never know in straightforward earthly terms.

At this point in the dream my wife wakens me, and suddenly our daughter, who is still doggedly playing with the watch strap, appears in an entirely different light – her own mother’s double. As swiftly as I signed up to my own hybrid version of afterlife, I now see its absurdity. My certainty dispels so quickly that I cannot even get a grip on what it was that had, only seconds before, seemed so cosy and real. Any assurance I had is gone.

Of course, when my mind is more alert and my thoughts more earthbound, I realise that the popularly understood concept of reincarnation is the ultimate comfort-blanket with which our age soothes away all the traumas and difficult questions of life. Reincarnation focuses on this life, which we know, rather than on some other life which we can only dream of. Thus it works in the short-term to assuage any anxiety about mortality, and can even take the edge off grieving. As a long-term prospect, though, it has its drawbacks. In the sixth century BC Buddha developed the already existing idea of samsara, constant rebirth, and regarded reincarnation as something negative. He wanted to liberate his followers from the cycle of dying and being born since, far from welcoming the prospect of having another go at life, many of them were terrified by the prospect of death after death. If they had had hospices and morphine perhaps they would have thought differently, but at that time it was considered bad enough to have to go through all those final agonies once, without having to do it ad infinitum. Buddha taught of nirvana, not as a physical place akin to heaven where one might get off the treadmill, but as a psychological state of release, separate from death, that could be achieved in this life.

There is an enormous contrast, then, between the reality of Buddha’s teachings and my half-awake efforts at toying with reincarnation as something to keep grief and loss at bay when cold reason offers no relief. As a simple answer to the eternal dilemma of suffering, Buddha realised, reincarnation only works in parts. It introduces a tangible degree of justice into each individual death to replace the injustices of each individual life by teaching that sinners will return humbled and the righteous will enjoy greater favour in their next incarnation, but fundamentally it embraces earthly suffering as each individual goes on and on and on trying to achieve enlightenment.

There is another drawback, even to the caricature of reincarnation that is now embraced by many in the West as a way of avoiding their own mortality. Such a scheme of things can only reassure those who have a high opinion of their own merits. My mother, who suffered the ravages of multiple sclerosis for forty years with exemplary steadfastness, once admitted to me, devout Catholic though she was, that she had tried to imagine reincarnation, albeit distorted through the filter of Catholic guilt, but had decided that rather than get an upgrade she would come back as a cow and have to endure what for her was unendurable – flies constantly landing on her face and her having no way of shooing them away.

Flirting with reincarnation appeals only to that arrogant, selfish, self-absorbed part of us all that cannot quite believe that our own death will be the end. This is the eternal attraction of every other form of belief in an afterlife. We may act every day as though we disbelieve the inevitability of death – driving too fast along a rain-soaked motorway, hanging on to the tail lights of the car in front, popping pills which will give us a high but which may also kill us – but in the midst of our oddly ambiguous relationship with mortality, there is always the abiding thought that, even if the inevitable happens, our unique being, shaped so laboriously, must live on in some form. Surely we cannot just vanish in a split second.

Sometimes I sit at traffic lights, my foot twitching on the accelerator of the car, and try to contemplate what would happen if I shot out into the line of oncoming traffic. More specifically, what would happen if I killed myself doing it? Would it all go blank at once, as doctors tell grieving relatives, reassuring them that their loved one wouldn’t have felt a thing at the moment of death? Or would I, in best Hollywood tradition, float up out of my body and look down on the crumpled tangle of cars I had left in my wake? And, if there is an afterlife, at what stage does it kick in? Straight away, after the funeral when I have the Church’s blessing, or after a sojourn in purgatory when I have waited in a queue for a few months (or years) and people on earth have prayed for the repose of my soul? I’ve never been good at queuing, and even if I managed to stick it out, what would I get to at the end? Would I even recognise it as having any connection with what went before? Would it be a physical landscape, or an illusory one? Would it exist outside my imagination, or would it even exist at all? Would others be there too? Would they recognise me? Suddenly oblivion seems so much more straightforward. As the lights turn to green and I cautiously set off on my way, I realise that these seemingly overwhelming questions are so earthbound as to be trivial compared with what I am contemplating.

Yet what is absolutely true is that we fear death because we fear the unknown: the rich build monuments to earn immortality, the wordy write books which will sit in library catalogues forever after, and the competitive strain to get their names engraved on cups and shields and prizes. All offer a kind of life after death. For the majority, however, the choice is simpler: children and/or a belief in the afterlife are our antidotes to death, the best way of cheating what scientists in a secular age tell us is the unavoidable fact of oblivion. Children can, of course, let us down as they grow up – run away from home, never darken our doorstep, and, God forbid, even predecease us – but afterlife never will. Potentially, it is the ultimate happy ending. As, it would seem, we cannot try it out and report back any feelings of disappointment, it remains nothing more than a glorious but untried promise, utterly open to the wiles of our imagination.

Yet it is a promise that is so finely attuned to our own needs and desires that it has been with humankind from the start, predating written language and philosophy and organised religion. From the time when the first Neanderthal sat next to the lump of dead protein that had been his or her mate and realised that something had to be done about the smell, we have wondered what, if anything, comes next. People have generally assumed that there should be something. When that body was put in a cave or a ditch or on to a fire or pushed over a ledge into a ravine, the one left behind looked into the void that was left and felt an emptiness and abandonment. So arose the myths, traditions and literature, the shamans and soothsayers, the priests and popes, and the poets, writers and dramatists who would attempt to provide the answer.

And so arose, too, that intimate connection between belief in a God and the hope of reward with Him or Her in life everlasting. In many faiths – particularly Western – the two are synonymous, and the link therefore goes unquestioned, but not all the world’s great religions have signed up for the two-for-the-price-of-one package deal. Buddhism has its deity, but though highly ambiguous and elusive it is basically indifferent to the notion of afterlife, which it regards as a red herring, and as something that makes religion other-worldly, irrelevant and even pessimistic. To treat nirvana as heaven would distract one from the pursuit of enlightenment in this life. Buddhism advocates the reaching of a higher state in this life rather than letting one’s dreams of a better time to come after death take hold. So Buddhism challenges its adherents to do the right thing now, for its own sake, rather than have half an eye on what might happen after death, thereby preventing any possibility of opting out of this world, standing aloof from it as certain religious groups have done down the ages, or even, as in the case of the various gnostic sects, rejecting this world as irredeemably evil. When there is nothing to work with other than the now, you have to get on with it, engage at every level. Buddhists believe one’s fate in both the present life and forever is bound up in this engagement. Most importantly, Buddhists must work to make the earth a place of justice rather than rely on inequalities being sorted out posthumously by the deity. There is no excuse for accepting the status quo.

Put briefly and in such terms, it sounds so attractive that it suddenly becomes hard to understand why the notion of heaven ever put down such deep roots. And this conviction strengthens when Buddhism’s rejection of a theology which places a greater premium on the afterlife than it does on this life is seen in the context of similar creeds which arose in the same period, roughly from 700 BC to 200 BC, known to historians as the Axial Age. Hinduism in India and Confucianism and Taoism in the Far East all stress the importance of practical compassion and concentrate on the here and now.

Yet not all faiths at this transition point in the history of religions took the particular route that excluded any great concentration on heaven. Judaism, and thereafter by association its younger sister, Christianity, was the main exception to the Axial Age trend. Infected by Zoroastrianism during the Babylonian exile (586–536 BC), Judaism has lived ever after with a highly developed eschatology (the doctrine of the last things which revolves around death, judgement and afterlife). This eschatology came as part of a parcel of beliefs. Judaism, which had hitherto flirted with other deities, also adopted a strictly monotheistic approach from Zoroastrianism. Unusually for its time, it taught of a single, good god – Ahura Mazda, the god of light – rather than a pantheon of gods and ancestor or nature spirits. Christianity and then Islam were later to join the ranks of the monotheistic faiths and also have a strong concept of heaven.

There is then a link between extolling the virtue of a single God, responsible for everything on this earth, and belief in an afterlife. If you centre your hopes, prayers and expectations on just one God, you inevitably concentrate on the ‘personality’ of that God, so much more than you would if you have tens or hundreds of gods to choose from, and, as a consequence, you nurture a hope of making contact with that God face-to-face.

This narrow focus takes its tolls on imaginations, or at least channels them in a particular direction, and often makes for a palpable sense that God must be near at hand. This in its turn leads to an exaggerated interest in the place where God lives and to where the faithful might one day travel. But the chain of connections between monotheism and heaven goes deeper. The omnipotent God upheld by monotheistic faiths embodies good and evil in a single source, as opposed to parcelling both out across a whole range of spirits, some of them two-faced. Christianity may itself have diluted this by invoking the devil in practice at least, if not in theory, as an equal and opposing force to God, but that should not distract from the fact that the creation of such a powerful, unified divine principle inevitably brings with it a sense of humankind’s smallness and impotence before their God, and also, therefore, a turning away from each person’s individual resources (as preached in Eastern faiths) towards a greater public search for oneness with the divine which necessitates a public arena – i.e. heaven – for fulfilment.

The tension between the two radically different emphases – on this life and on the next life – is, in effect, both the argument for and against heaven. Both have their strengths. The first places great and potentially empowering emphasis on each person to cultivate an internalising spirituality. For some this burden is too much of a challenge. Putting it all off until after death with the promise of a heaven – especially one where, as in the Christian New Testament, God will roll out the red carpet for the workers who only spend the last hour of the day in His vineyard as readily as He will for those who have toiled since sun-up – is much more palatable. Death-bed repentance, in theory at least, allows for brinkmanship – a life of wonderful hedonism followed by a last minute change of heart, half an hour of piety and remorse and then a heavenly hereafter.

For some, the ‘jam tomorrow’ approach of monotheism belongs in the nursery, but to its adherents, in more mature vein, it offers consolation in the face of the inevitability and finality of death. It also requires a moral framework which can be carefully calibrated (often by clerical hierarchies) as a step-by-step guide to achieving a good afterlife. Immanuel Kant, the eighteenth-century German philosopher and religious sceptic, once remarked that without heaven no system that sought to teach, preach or impart morality could survive.

How to decide between the Eastern and the Western approach? Conventional wisdom – shared for once by scientists and clerics – is that there can be no verifiable communication with the other side as a way of assessing which has most merit. Central to Eastern ideas of rebirth is forgetting all that has gone before. There have always been, however, unconventional individuals able to service those who are too restless to wait and see. The Victorians went to spiritualists and mediums; we, in our turn, devour the literature of near-death experiences to satisfy our hankering to know if there is anything more to come. The American bestseller, Hello from Heaven (edited by Bill and Judy Guggenheim), was a collection of 353 accounts of communications from beyond the grave.

To accept absolute oblivion after death, a brain that stops functioning and a body that rots, would be to accept the polar opposite of heaven. It is increasingly popular as an option. There is even some scriptural foundation for such a stance: in the Old Testament, Job suffers endless adversity as part of a debate between Yahweh and Satan on the nature of human goodness. When he survives the ordeal, his reward is to have ‘twice as much as he had before’ in this life. There is no suggestion that there is any other.

Most of us, however, find the idea that death is the end unappealing, unthinkable or untenable – or a combination of all three. We cling fearfully and in hope to the notion, common in monotheistic religions, of the soul, that invisible but integral part of us that is above the messy business of physical death. Yet despite its enduring popularity, a heavenly hereafter for the souls of the faithful departed has been officially declared by the mainstream churches as being beyond our imagination.