По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

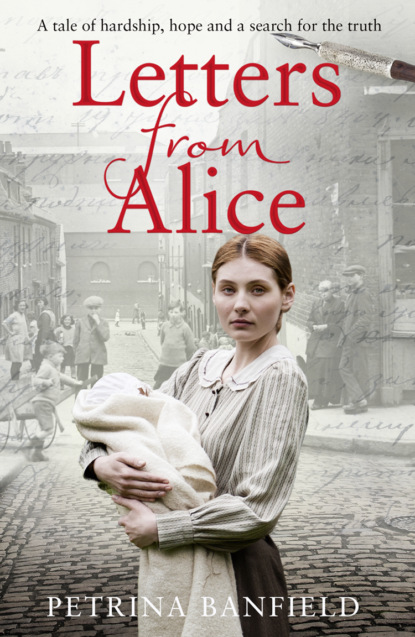

Letters from Alice: A tale of hardship and hope. A search for the truth.

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The tell-tale signs of a scabies infestation were visible along John’s forearm. Track-like burrows ran around his wrist where a mite had tunnelled into the skin, the tiny black dots of faecal matter visible around an angry rash. It was something Alice and the other VADs had often seen in the field hospitals; soldiers driven half-mad by the intense, irrepressible itch. The entire family would need to be treated with benzyl benzoate emulsion. ‘Not at school, Charlotte?’ Alice asked, in a precise but friendly tone.

It was a question designed to engage, rather than a genuine enquiry. The almoner had been taught specific interviewing strategies in training that helped her to disguise carefully planned interviews as casual chats, thereby gaining valuable insight into the living conditions of her patients: their relationships, finances, thoughts and fears. By examining individuals in the context of their social setting she was able to identify issues that might be impacting negatively on their health. Practical help honed to individual needs could then be offered, improving outcomes and the chances of a good recovery.

One way to encourage an interviewee to relax was to start a conversation with questions that were most easily answered, in much the same way as the devisers of written exams open with a problem easily solved. Since patients almost universally enjoyed talking about themselves, she learned that a readiness to listen, a keen interest in people and a sincere desire to help were all that was needed to encourage loose tongues.

‘I’m fifteen,’ the girl said, sounding offended. ‘I left ages ago.’

Alice nodded. ‘So are you working outside of the home now?’ The almoners knew it wasn’t unusual for older children to take a job so that they could contribute towards the family purse, even skipping school to do so. The income generated was often kept under wraps by families being assessed. Alice had been taught to be thorough in her questioning to uncover a true picture of a family’s finances.

‘Not really,’ Charlotte answered quickly. Her thin chilblained fingers worked continuously at the blanket on her brother’s lap, as if she had more to say. Alice waited, but the girl’s eyes flicked over to her mother and then her expression suddenly closed down. Her shoulders rounded further away so that the child on her lap wobbled and almost lost balance until she reached out and wrapped her arms around his waist.

Alice pressed her lips together, rescued her hat and rose to her feet. Over by the door, Frank’s charms were working a treat, Mrs Redbourne smiling up at him coyly. She barely seemed to notice when Alice slipped past. Behind her, Charlotte sat quietly, eyes watchful.

In the hallway, Alice hesitated. She stood in solitary silence for a few seconds, head cocked as if listening. After a moment she turned sideways to squeeze past the pram and then moved towards a closed door at the end of the hall. A soft thump stopped her in her tracks. There was a creaking sound, and then the door gave way, a pair of eyes peering through the crack.

After a short pause in which no one moved, the door was opened to reveal a fleshy, puffy-eyed man with a glossy sheen across his forehead. Alice strode towards him, thrust out her hand and smiled, as if a meeting had been planned between them. ‘You must be Mr Redbourne?’ she said. ‘Alice Hudson. Pleased to meet you.’

The man looked down at her and passed his tongue over his lips, then took her proffered hand. ‘You’ll be from the hospital,’ he said in an uncertain voice. ‘The wife could do without the added pressure,’ he added, when Alice confirmed her occupation. ‘We do what we can, but you can’t expect us to give what we don’t have.’

He followed her to the living room, but when his wife caught sight of him she shooed him away with her hand. ‘I thought you were at the market, George? Get going will yer, there’s things we need.’ Mr Redbourne pulled a pack of cigarettes from his pocket, took one into his mouth using his teeth, then, without another word, slipped out of the house.

When the front door clicked to a close, Alice entered the room he had just vacated. The back parlour was a dark room with a single bed in the centre, the wooden base held up by a pile of bricks at each corner. There was a bite to the air, the room colder than the street outside. A dozen shirts hung from a rope stretched diagonally across it, one end caught between the slightly open window and the other wedged between the top of a Welsh dresser and the wall.

Alice closed the door and peered into the nearby kitchen. Through the small window at the end of the room, a partly stone-flagged backyard was visible, a patch of bare earth beyond. An old lean-to housing the lavatory blocked what little winter light there was from entering the kitchen. There was no sign of running water; most working-class families were still filling buckets from a pump at the end of their street. The approaching twilight bathed the small area in shadows, the air fermenting with the smell of old dinners. With so many people living in the house the room was likely a place of much activity but, aside from a few black beetles scurrying across the floor and over the draining board, the overriding air was one of long abandonment.

The feeling of bleakness prevailed as the almoner made her way up the stairs. The rising wind caused a stray branch to tap rhythmically at the panes of the landing window, almost as if in warning.

It was a degree or two warmer upstairs than the kitchen had been but Alice shivered nonetheless as she ventured into the first bedroom. Bare, chipped floorboards bowed towards the middle of the room, the undulating surface and the sour tinge in the air adding to the general sense of unease.

Nothing stood out as being out of place. The bed, presumably belonging to Mr and Mrs Redbourne, stood low to the floor. Covered with a tatty, slightly stained tufted counterpane, it sagged drunkenly, as if in sympathy with the floor. Droopy curtains hung half-closed at the windows and an old leather suitcase stood up on end in front of a dressing table of dark wood, perhaps as a makeshift stool.

Back in the hall, another staircase wound itself over the first, leading to the second floor. Notes in the file showed that Mrs Redbourne had been specifically questioned about the empty rooms upstairs by the Head Almoner, Bess Campbell, who suspected that they may have been sub-let. Mrs Redbourne claimed that the space was uninhabitable due to damp walls and unstable floorboards, but the almoners had visited families who had carved living spaces into stables and coal bunkers; a loft space, however unsafe, would have been appealing enough to command at least a few shillings in rent from a desperate family.

Foreign voices and a clattering of footsteps drifted down through the floorboards, followed by a loudly slammed door. The window in the hall rattled in protest. Alice turned and stared at the cracked ceiling before moving further along the hall to a much smaller room.

Here, the entire floor was hidden by a horsehair mattress and an assortment of fraying blankets and clothes. In the twenty-six years since the first almoner was appointed in 1895, much intelligence had been gathered about the sort of secrets that could lay buried within families. As seekers of truth, the almoners knew that sometimes the sinister could be masked by a cloak of ordinariness. It was one of the reasons they were told not to hurry their home inspections, but to take their time, so that the hidden might somehow reveal itself.

Alice stood quietly in the doorway, running her eyes around the room. It was only at the sound of purposeful strides on the stairs that she finally turned around.

The face of Mrs Redbourne’s eldest daughter rose over the top of the banisters. The rustle of linen as the hem of Charlotte’s skirt brushed the stair beneath her feet seemed to whisper something other than her arrival. In the light of the upstairs hall, the shadows under the girl’s eyes became apparent, her cheeks speckled with a deep scarlet flush.

The almoner didn’t say anything; probably hoping not to attract attention from other family members. Instead, she took a step closer to the young woman and gave a reassuring smile. In that fleeting moment, the teenager’s desperation became evident.

After a wild glance behind her, Charlotte bit her bottom lip and then opened her mouth to speak. When no words came, Alice frowned and whispered: ‘Charlotte, are you alright?’

‘F-fine,’ the teenager stammered, the word at odds with her countenance. ‘But I-I think you should know –’ She stopped, then burst into tears. Alice’s fingers curled towards her palms, as if trying to encourage her to speak. ‘W-what I mean is, I should have said something sooner, but it’s too late now and …’, she faltered, her choked whispers stilted by the click of a door latch above.

Alice looked up. A middle-aged bespectacled gentleman wearing a long overcoat descended the stairs, a scarf knotted under his bearded chin. Charlotte whirled around and then scurried away, her long skirt fanning out behind her.

‘Good day, Madam,’ the man said in a heavy accented voice. Alice nodded and waited in the hall as the man traced Charlotte’s footsteps downstairs. The almoner’s expression was serious. As soon as she had crossed the threshold of the Redbourne’s home, something had struck a false note.

By the time she left, she later recorded in her case notes, it appeared as if something truly disturbing were about to unfold.

Chapter Two (#u71057930-510a-59d4-be5f-83948873ab46)

The out-patient department, which annually receives over 40,000 cases, is at present conducted in the basement, which is ill-lighted and insufficient in accommodation … The hospital is situated in one of the poorest and most crowded districts of London …

(The Illustrated London News, 1906)

It was still dark when Alice woke two days later, on Monday, 2 January. Three years into the future, in 1925, the live-in staff of the Royal Free would move to purpose-built accommodation on Cubitt Street. The bedrooms of the Alfred Langton Home for Nurses were clean and comfortable, according to the Nursing Mirror, each one having ‘a fitted-in wardrobe, dressing table and chest of drawers combined. Cold water laid on at the basin and a can for hot water, and a pretty rug by the bed … everything has been done for the convenience and comfort of the nurses’.

As things were, the nurses managed as best they could in the small draughty rooms of the Helena Building at the rear of the main hospital on Gray’s Inn Road, where the former barracks of the Light Horse Volunteers had once stood. Huddled beneath the bedclothes, they would summon up the willpower and then dash over to the sink, the flagstone floor chilling their feet.

Alice’s breath fogged the air as she dressed hurriedly in a high-necked white blouse, a grey woollen skirt that skimmed her ankles and a dark cloche hat pulled down low over her brow. After checking her appearance in the mirror she left her room and made for the main hospital, where the stairs leading to her basement office were located. Outside, a brisk wind propelled young nurses along as they ventured over to begin their shifts, their dresses billowing around their calves. The skirts of their predecessors a decade earlier, overlong on the orders of Matron so that ankles were not displayed when bending over to attend to patients, swept fallen leaves along the ground as they went.

Just before the heavy oak doors leading to the hospital, Alice turned at the sound of her name being called from further along the road, where a small gathering was beginning to disperse. In among the loosening clot of damp coats and umbrellas was hospital mortician Sidney Mullins. One of the tools of his trade – a sheet of thick white cotton – lay at his feet, a twisted leg creeping out at the side.

Sidney, a fifty-year-old Yorkshire man with a florid complexion and a bald crown, save for a few long hairs flapping across his forehead, often strayed to the almoners’ office for a sweet cup of tea and a reprieve from his uncommunicative companions in the mortuary. Standing outside a grand building of sandstone and arches of red brick, he beckoned Alice with a wave of his cap then stood back on the pavement, rubbing his chin and staring up at one of the towers looming above him.

Shouts of unseen children filled the air as Alice took slow steps towards her colleague. She dodged a teenager riding a bicycle at speed on the way, and a puddle thick with brown sludge. ‘What is it, Sidney?’ Her eyes fell to the bulky sheet between them, from which she kept a respectful distance away.

The mortician pulled a face. ‘Forty-summat gent fell from t’roof first thing this morning,’ he said, scratching his belly. A flock of black-gowned barristers swept past them, their destination perhaps their courtyard chambers, or one of the gentlemen’s clubs nearby that were popular retreats for upper-middle-class men.

‘Oh no, how terribly sad,’ Alice said.

‘A sorry situation, I’ll give you that,’ Sidney said in his broad country accent. He rubbed his pink head and frowned up at the building. ‘But I just can’t make head nor tail of it.’

Alice grimaced. ‘Desperate times for some, Sidney. It’s why we do what we do, isn’t it?’

The mortician pulled his cap back on and looked at her. ‘Aye, happen it is. But I still can’t work it out.’

‘What?’

‘Well, how can a person fall from all t’way up there and still manage to land in this sheet?’

Alice gave a slow blink and shook her head at him. ‘Sometimes, Sidney …’

He grinned. ‘Oh, don’t look at me like that, lass. You’ve gotta laugh, or else t’pavements’d be full with all of us spread-eagled over them.’

Sidney recounted the exchange inside the basement half an hour later, Frank banging his barrelled chest and chuckling into his pipe nearby. The smell of smoke, damp wool and dusty shelves smouldered together in an atmosphere that would likely asphyxiate a twenty-first-century visitor, though none of its occupants seemed to mind the fug. ‘Never was a man more suited to his job than you, Sid,’ Frank said, gasping. ‘You were born for it, man. What do you say, Alex?’

Alexander Hargreaves, philanthropist, local magistrate and chief fundraiser for the hospital, was a tall, highly polished individual, from his Brilliantine-smoothed hair and immaculate tweed suit all the way down to his shiny shoes. A slim man in his late thirties, his well-groomed eyebrows arched over eyes of light grey. In the fashion of the day, an equally distinguished, narrow moustache framed his thin lips. There was a pause before he answered. ‘I prefer “Alexander”, as well you know, Frank,’ he said, without looking up from the file on his desk. ‘In point of fact,’ he added in a tone that was liquid and smooth after years of delivering speeches after dinner parties, ‘I don’t happen to think there’s anything remotely amusing about mocking the dead.’

The walls behind Alexander’s desk were lined with letters thanking him for his fundraising efforts, as well as certificates testifying to the considerable funds he had donated to various voluntary hospitals over the years. Framed monochrome photographs of himself posing beside the equipment he had managed to procure, developed in his own personal darkroom, were displayed alongside them.

Sidney’s podgy features crumpled in an expression of genuine hurt. Years in the mortuary had twisted his once gentle humour out of shape until it was dark, wry and, to some, wildly offensive, but his respect for the gate-keeping role he played between this life and the grave never wavered. ‘Right,’ he said a little forlornly, clapping his hands on his podgy knees. ‘I reckon I’d best get back to the knacker’s yard.’

Alexander’s nostrils flared. Frank arched his unkempt brows. ‘Come on, Alex, where’s your sense of humour?’