По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

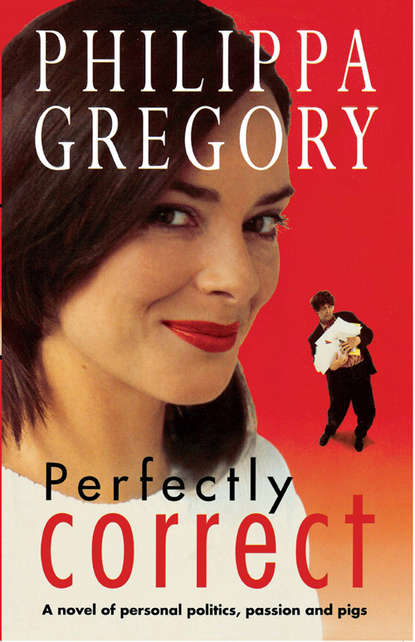

Perfectly Correct

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘You met us in our finals year,’ Louise reminded him. ‘Our salad days were over then. It was all continuous assessment when we were students. We were on the rack from September to June.’

‘But more thoroughly assessed,’ Toby prompted.

He and Louise had fought an easily defeated campaign to preserve the university’s practice of continuous assessment, in which students demonstrate their learning and research skills with work written over weeks of preparation. In practice, the conscientious ones worked themselves into a stupor of fatigue with week after week of late nights and early mornings, while the lazy ones drank to excess and fooled around until two days before the deadline when they went into a frenzy of last-minute labour. The results were broadly comparable.

The university, weary of supervising students rushing to extremes, had instituted the convention of a finals exam fortnight so that all the breakdowns and alcoholism and suicides were concentrated into one short, manageable period.

Louise and Toby had fought this change on the grounds that it was a deviation from the radical nature of the university. Of course, no-one had ever proved that continuous assessment was more or less radical than examinations, and once continuous assessment was adopted as the Conservative government’s policy for GCSEs it had rather gone out of fashion as a Cause. Nonetheless Toby and Louise still loyally paid lip service.

‘I learned more in my final year than I did in the other two put together,’ Louise said.

‘I wish I’d had that opportunity,’ Toby sighed, hypocritically hiding his pride in his own degree. ‘Finals fortnight at Oxford was madness.’

He glanced at the kitchen clock, drained his glass of wine and stood up. ‘See you tomorrow.’

Louise followed him from the kitchen to the sitting room and passed him his jacket. She was attractively dressed in a silky dressing gown. Toby had a moment’s regret that he was leaving her to go into the cool summer night and drive home to Miriam who would be irritable and worried from her meeting at the Alcoholic Women’s Unit.

‘I’m not coming in to university tomorrow,’ Louise reminded him. ‘I shall make sure the old woman moves on and then I’ll work here all day. I’m overdue on that Lawrence essay.’

Toby hesitated. It would be fatal to his plans if the old woman disappeared again into the lanes of Sussex with her precious bundle of primary sources and her irreplaceable oral history. But he could not think of any reason to stop Louise from moving the trespasser on her way. All he could do was delay her. ‘I’m free in the morning,’ he said. ‘I’ll come out and have breakfast with you. I’ll bring fresh croissants and the newspapers.’

Louise lived far beyond the restricted village paper round which was organised by Mrs Ford from the village shop and delivered only to her particular favourites. Louise adored reading the Guardian over breakfast. Toby had played one of his strongest cards.

‘Oh, how lovely!’ she exclaimed. ‘To what do I owe the honour?’

Toby smiled his engaging smile. ‘Oh, I don’t know. I just thought we could spend the morning together. Don’t get up before I arrive and I’ll bring it up to you in bed. I’ll be here by nine.’

Louise wound her arms around his neck and kissed his cheek and his ear. ‘Lovely lovely man,’ she said softly.

‘Promise you won’t get up?’ Toby demanded cunningly. ‘I don’t want you to spoil the mood by worrying about the old lady. You stay in bed until I come.’

‘Promise.’

He released her and she watched him walk from her front door to his car. Then she shut the front door and went to the kitchen to clear the plates from supper. She was thoughtful. This was the first time Toby had offered to bring her breakfast since the move to the cottage. In the old days, in her little studio flat, he had often climbed the stairs with his copy of the Guardian and croissants hot from the bakery in a greasy paper bag, after Miriam had left for work. The transition of this tradition to the cottage could only indicate his increasing commitment.

She wiped down the pine table with a sense of fluttery excitement. Toby had been with her this morning, teasing, withholding, but playing with her and not his wife. He had been with her all evening, and now he was coming to breakfast. His movement towards her was evident. Since the start of their affair Louise had wanted him to choose her. The underground half-conscious competition between close women friends meant that Louise and Miriam were always rivals. The women’s movement’s insistence on loving sisterhood had meant that both women totally ignored this. If challenged they would have denied any feeling of rivalry; but in fact Miriam was always worried that she had made the wrong career choice when she decided to work for the refuge and leave the academic life which had been so good for Louise; while Louise’s sexual confidence would always be undermined by her memory of the three long summers when Miriam attracted scores of young men by doing nothing more seductive than lying on the grass and picking daisies. Only one thing could restore Louise to a proper sense of her own worth – Toby.

Louise went through to her study to collect the vexing copy of The Virgin and the Gypsy to re-read once more in bed. A glimmer of golden light from the bottom of the orchard caught her eye. Now there was a woman who seemed to need no man at all. No friend, no husband, no lover, certainly not the husband of her best friend. Louise stood for a little while in the darkness of her study looking out at the friendly little light, considering the old lady. There was a woman who seemed powerfully self-contained. Not a property-owner like Louise, not a career woman like Louise. Not a sexual object like Louise – left alone again, despite her silky sexy dressing gown. A woman who had avoided all the opportunities and all the traps open to the modern woman. A woman who had been born into a society markedly less free, a woman who enjoyed none of Louise’s opportunities and enhanced consciousness but who was, nonetheless, an independent woman in a way that Louise was not.

Louise speed-read the whole of The Virgin and the Gypsy before she went to sleep. Although she had taken English Literature as her BA and was now a women’s specialist in the Literature department, Louise was quite incapable of understanding either fiction or poetry. All of it was judged purely on its attitude to women. She had learned the jargon and skills of literary criticism. She could point to an adjective and detect imagery. But the heart of her interest in writing was neither the story nor the telling of it, but its attitude to the heroines.

Any work of fiction could thus be simply de-constructed and simply scored on a grade of say one to ten, entirely on the basis of its position on women. The language might be living vibrant poetry, the story might bypass Louise’s critical pencil and plunge straight into her imagination, but still she would work through the pages going tick, tick, tick in the margin for positive references to women, and cross, cross, cross for negative imagery. A piece of blatant sexism would be flagged with a shocked exclamation mark. TheVirgin and the Gypsy was spotted with outraged exclamation marks by the time that Louise’s bedside clock showed midnight and she had finished re-reading it.

She closed the book carefully and put it on her bedside table. She set her alarm clock for quarter to eight. She had promised Toby that she would not get up before he arrived with her breakfast but she was not going to be found in bed in her brushed cotton pyjamas, her hair tangled, and her mouth tasting stale. When Toby arrived, thinking he was waking her, she would have already showered with perfumed shower gel, cleaned her teeth, brushed her hair, and changed into silk pyjamas which matched the dressing gown she only wore for Toby’s visits.

She glanced towards the darkened window. There was a pale wide moon riding in the skies over the darkened common. An owl hooted longingly. Up the little lane came the strangled roar of a Land-Rover in the wrong gear: Mr Miles driving home after a late night at the Holly Bush. The sound of the engine faded as he turned the corner towards his solitary darkened farm and then everything was quiet again. Louise turned on her side and gathered her pillow into her arms for the illusion of company, and slept.

She dreamed almost at once. She was in Toby and Miriam’s house but the road before their front gate was a deep brown flood of a river. At the edge of the churning waters, where the waves splashed and broke against the front doorsteps, was a tossing flotsam of paperbacks, their pages soggy and sinking in the dark waters, their covers ripped helplessly from the spines and rolling over and over in the turbulence of the flood.

Louise began to be afraid but then realised, with the easy logic of dreams, that she could go out of the back door, into the little yard and through the backyard gate, where she put out the dustbins on Thursdays. From the backstreet she could go to the university, to her office, where there were plenty of books to replace those that were rushing in the flood past the house, torn and soggy. She went quickly through the kitchen and flung open the back door.

It was the very worst thing she could have done. With an almighty roar, like that of some wild and uncontrollable animal, the flood water rushed towards her, far higher and more violent than it had been at the front. Louise fled before it as it tore the notes from the cork pin-board and clashed saucepans in their cupboards. The larder door burst open and packets of cereals and rice tumbled out into the boiling waters. Toby’s wine rack crashed down and the bottles broke, turning the water as red as blood and terrifyingly sweet. Louise ran for the stairs, the red waves lapping and sucking at her feet as the current eddied and flowed through the ground floor of the house. She screamed as she grabbed the newel post at the bottom of the stairs but there was no answering call from above. She was alone in the whole world with the hungry waters after her.

She staggered up the stairs as a fresh high wave billowed in through the kitchen door. With a crash the front door fell in and the two rivers merged, swirling, in the hall. The scarlet waters’ terrible load of tumbling books chased Louise up the stairs, past Toby and Miriam’s bathroom and bedroom, up the little stairs to her own flat.

There was someone in her bed. A man. For a moment Louise recoiled in fear, and then the crash behind her, as the stairs gave way, made her run into the room and fling herself on him, terrified at last into desire. She was screaming, but not for help. She was screaming: ‘I’m sorry! I’m sorry! I’m sorry!’

Louise wrenched herself from sleep with a gasp of terror. Her pillow, gripped in her arms, was damp with warm sweat. Her hair was plastered to her neck as if she had indeed been washed by the waters of that strange dream flood. She swallowed painfully, her throat was sore. She unclenched her fists, she released the pillow.

Her bedroom was very quiet. The clock ticked very softly. She looked towards the window. Dawn was coming, the first she had ever seen in the country. In the soft pearly light of the early morning a few solitary birds were starting to sing. Louise raised herself up in her bed and looked down towards the orchard. The blue van was there, with a tiny wisp of smoke coming from the skewed chimney. The van was rocking slightly as the old woman inside moved about, making breakfast for herself and the dog. Louise sniffed. She could smell a safe warm smell of woodsmoke. She felt enormously comforted at the sight of that battered blue roof and the presence of another person nearby. She dropped back to the pillows again and fell asleep like a child that is reassured by the sound of her mother in the next room. There was, after all, nothing to fear.

Friday (#ulink_e90e58fc-3b2c-5579-b5de-6eee21af76b5)

TOBY WAS PROMPT, anxious that Louise should not have broken her promise and moved the old woman on. Before he let himself in at the front door he put down the packages on the doorstep and went quietly down to the caravan in the orchard.

The old woman was sitting in her doorway, face turned upwards to the weak morning sunshine. She smiled at him when she saw him but she did not move. The dog raised his head and lifted his ears and gave a soft warning growl.

‘Hush,’ the old woman said gruffly.

At once the dog dropped down to watch Toby in silence.

‘I’ll come and talk to you later,’ Toby said. ‘If I may.’ He smiled his most charming smile. ‘I’m longing to hear about your childhood. Could you spare me some time this morning?’

The old woman looked thoughtful. ‘I promised her I’d leave,’ she said regretfully. ‘She doesn’t want me in her orchard. I should be moving on today. I’m about ready to get packed.’

Toby let himself through the gate, the words spilling out in haste. ‘Oh, don’t go, don’t go. There’s no need for you to go. I’ll talk to Louise. She doesn’t really want you to go. You needn’t leave for a week or so. I promise.’

The old woman smiled at him. ‘As you wish,’ she said gently. ‘I’d rather stay. I’ve some problem with the van that needs sorting. Mr Miles’ll do it for me. I could get it fixed here and then move on later.’

Toby nodded. ‘You do that. I’ll be out later. In about an hour.’

The old woman graciously assented. ‘All right, then. I’ll be here.’

Louise, watching the two of them from her bedroom window, wondered what Toby wanted with the old woman. If it had been Miriam seeking her out then Louise would have known that she had found her a settlement place, a bed in a refuge, a council site. But Toby – Toby never did anything for anyone but himself.

Louise slipped into bed and arranged herself attractively on the pillows as the front door opened and Toby’s footsteps sounded on the stairs.

‘Darling,’ he said as he came into the room and laid the Guardian on her white counterpane. ‘Darling.’

‘The old woman’s van has got some mechanical problem,’ Toby said after he had made efficient but perfunctory love to Louise, unpacked the croissants and drank coffee, all in a rather bohemian mess in Louise’s wide white bed.

Louise watched him, her eyes hazy with post-coital content.

‘She told me Mr Miles would fix it for her if she could stay a few more days. I said I was sure you’d let her.’ Toby put on his little-boy-pleasing face. ‘I was sure you wouldn’t really mind.’

‘I do mind,’ Louise said abruptly. ‘I don’t want her here. I didn’t ask her to come here. And I particularly dislike the way she interferes. She talks to you, she watches my front door and knows when you’re here. God knows what arrangements she has in there for hygiene. Mr Miles has a thousand empty fields. If she’s on such good terms with him, why doesn’t she go up there?’

Toby reconsidered rapidly. As long as he knew where the old woman was, it would actually be more convenient if she were not on Louise’s doorstep. A casual remark from her about Sylvia Pankhurst, and Toby’s research would have to be shared with Louise, and the rewards shared too. But if she were safely housed away from Louise then he could develop the interviews at a leisurely, appropriate pace, and Louise would not find out about it until he had a contract from a publisher and an exclusive agreement with the old lady.