По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

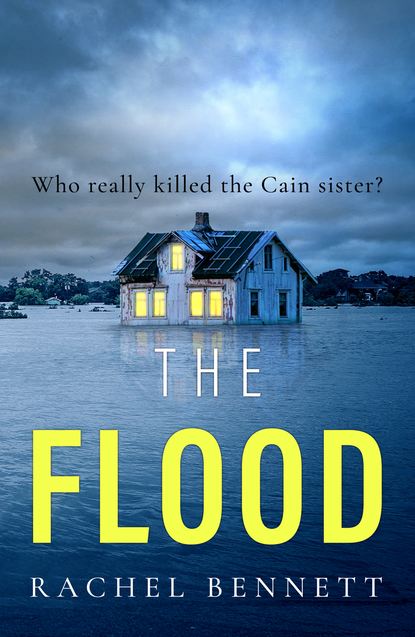

The Flood

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

That sounded like a lie, but Daniela let it pass. ‘So how about five thousand? That’s not unreasonable, is it?’

Stephanie was already laughing. ‘You’re hilarious, Dani,’ she said. ‘Not unreasonable.’ Again, she shook her head. ‘Perhaps if you’d picked up the phone and asked, I might’ve paid five thousand to avoid seeing your face.’

Ouch.

‘I tried calling,’ Daniela said. ‘You didn’t answer.’

‘And can you blame me?’

‘I’ve never asked you for anything.’

‘You’ve never given much either.’ Stephanie stood and retrieved her hat. ‘Well, this has been a barrel of laughs, but I’ve work to do.’

‘Sure. Have fun policing the sandbags. I’m sure it’s giving you job satisfaction.’

‘I’m surprised you know the meaning of the term.’ Stephanie tipped her hat. ‘See you in another seven years.’

As Stephanie turned away, Daniela asked, ‘Did you ever find her?’

‘Who?’

‘Mum.’ Daniela studied her sister’s face. ‘I know you and Franklyn were looking for her.’

Stephanie’s expression closed up again. ‘We stopped looking a long time ago.’

After Stephanie left, Daniela sat by the window for a while. She drank her pint slowly, not wanting to brave the cold outside.

‘Can I get you a refill, youngster?’ Chris called from the bar.

Daniela shook her head and finished the dregs. As an afterthought, she drank Stephanie’s untouched coffee as well. It was cold and bitter. ‘I’d better get moving. Thanks anyway.’

‘So, have you decided if you’re staying or not? I can get the missus to make up a room.’

Daniela felt despondent enough to wade the five miles back to Hackett and catch the first bus she saw. But she hated giving up.

And, of course, there might be another way she could get her money.

She shook her head, smiled. ‘It’s okay. I think I might go home instead.’

3 (#ulink_cac25add-fb95-51f0-bba3-b84b68772d4b)

In the afternoon the sky darkened again with low-bellied rainclouds, ready to shed their weight at the slightest provocation.

Daniela hadn’t anticipated how cut off the flooded village was from the rest of the world. Only a few houses were occupied, and the light from their windows was weak and tremulous, as if aware that the power could die at any second. Looking at the surrounding fields, with the pylons standing in a foot of water, Daniela was surprised the lights were still on, but, according to Chris in the pub, that was usual unless the substation itself was underwater.

A landslip to the west had felled the phone lines. Daniela kept checking the faint signal on her mobile. Amazing that a little rainfall could isolate a whole village.

Daniela ate lunch in the pub – the kitchen was closed, but Chris grilled a fair panini – sent a few text messages, then bundled herself up in her less-than-waterproof clothes. After an hour by the fire in the lounge, her boots were only a little damp inside, her jacket pleasantly toasty.

The warmth didn’t survive for long. By the time she’d slogged along the back street to the other end of town she felt the cold again. A light drizzle flattened her hair and chilled her exposed skin. She pulled up her hood and waded on.

The back lane took her around the main street, because she had no desire to chat to the group who were sandbagging the gardens. She’d wanted to get in and out of town without talking to anyone except Stephanie.

Daniela ground her teeth. Stubborn, awkward Steph. It’d been a pleasant daydream, to imagine her sister would hand over a wad of cash without blinking. She might at least have listened.

Daniela shook the thought away, set her shoulders, and kept walking.

The old family house was a half-mile outside town, along a narrow lane flanked with high hedgerows. As a child, Daniela had walked that road twice a day, every day, since she was old enough to walk. It held a familiarity like nowhere else in the world. Every footstep felt like a journey home. It wasn’t entirely comforting.

The lane rose and fell with the undulations of the land, too slight at normal times to notice, now dotted with tarmac islands that stood proud of the water. In places Daniela was forced to wade. She was careful not to flood her boots again. She also stayed clear of the ditches that edged the road; hidden sinks at least three feet deep.

As she left the village behind, the road wound into the woods. The hedgerows gave way to barbed wire fences. Slender elms and beeches crowded the skyline, their bare branches scratching as they moved with the wind, their roots swamped in mud and water. A rippling breeze scooted fallen leaves across the pools.

At another time, Daniela would’ve abandoned the road, ducking under the fence to follow the hidden pathways of the wood. Part of her yearned to rediscover the secret places where she and her sisters had played as children. The hollows where they’d made dens; the winding streams where they’d fished for minnows. Trees for climbing, root-space burrows, hollow deadwoods …

She paused to light a cigarette. It’s gone. Even if it’s still there, it’s gone. Those places are muddy grot-holes, or piles of branches, or fallen trees. You are definitely too old to grub around in the dirt looking for your misspent youth.

The family home stood in a shallow depression, hidden by trees until the road turned and it was suddenly right there. Daniela had to brace herself before taking those last few steps.

She was prepared for the house to look exactly as she’d left it. She was equally prepared for it to have been modernised and updated beyond recognition. What she hadn’t expected was it to be derelict.

The house was once elegant, with a wide, many-windowed front and arching gables, but neglect had made it slump, like an old lady giving up on life. Its timbers had slouched and its roof was sloughing tiles. The paintwork had peeled and cracked. A broken window was patched with cardboard. The woodpile under the awning had mouldered into a heap of rotting, moss-covered logs.

It didn’t help that rain had flooded the shallow depression, and the house sat in a lake of dirty water.

How did this happen? In Daniela’s memory the old place was alive, awake, with washing lines strung across the garden and toys scattering the front lawn. Now there wasn’t so much as a light in the window or a trail of smoke from the chimney. At some point in the intervening years the old house had died.

She’d thought Stephanie had been evasive about how little the house was worth. Now she saw the truth. No wonder they couldn’t sell the place.

She made her way down to the front gate. It was wedged open by years of rust.

The water was almost a foot deep around the house. Daniela felt her way along the path. Ripples sent reflected light bouncing across the windows. A half-hearted stack of sandbags guarded the front door.

Halfway up the path, Daniela paused to listen. The only sounds came from the wind in the trees and the occasional hoot of a woodpigeon somewhere among the stripped branches.

Daniela reached the front door. A piece of sticky tape across the inoperative doorbell was so old it’d turned opaque and flaky. She leaned over to peer through the sitting-room window. Floodwater had invaded the house as well. The front room was awash, the furniture pushed back against the walls, a few buoyant items floating sluggishly. Obviously the sandbags hadn’t done the trick.

She felt a flush of anger at Auryn. Why hadn’t she made sure the place was watertight before she left? And what about Stephanie? She was right here in town but hadn’t bothered to keep an eye on the house?

The front door was locked. In a village like Stonecrop, people hardly ever locked their houses, except when they went away. But Daniela had kept her key, or rather she had never got rid of it. It was still strung on her keyring like a bad reminder. So long as Auryn hadn’t changed the locks …

She hadn’t. The Yale clicked open. Daniela pushed the door but the water held it closed. She leaned her weight onto the wood and pushed it open a half-inch. It was more than just water behind. More sandbags, possibly. She couldn’t open the door enough to get her foot into the gap.

Giving up, Daniela stepped off the path and made her way around the side of the house. Clouds of muddy water swirled around her wellies. Now she risked not just flooded boots but tripping over the uneven ground into the freezing water. She kicked aside debris with every awkward step.

At the side of the house, the small vegetable garden was now an empty lake. A few tripods of discoloured bamboo canes protruded like totems. Against the far wall, the old beehive was a pile of mushy timbers. Dead leaves sailed like abandoned boats. Eddies of twigs had collected below the window frames. Daniela paused by the window of the utility room next to the kitchen, but the net curtains obscured her view.

There was more neglect at the rear. The back porch lay in a crumpled heap of broken wood and corrugated plastic, as if someone had angrily tossed it aside. The apple tree by the porch was dead. A frayed length of knotted rope still hung from a branch – the makeshift swing that Franklyn and Stephanie had put up.