По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

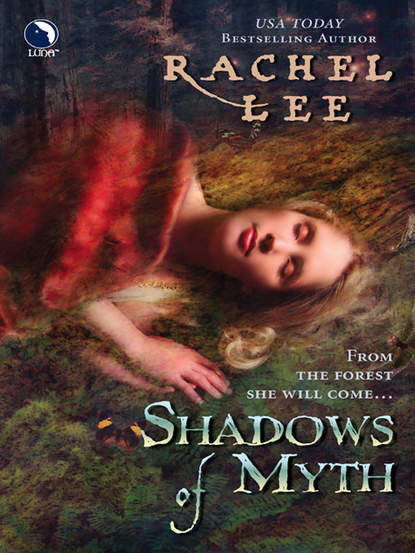

Shadows of Myth

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Twould be best to heed Giri’s warning and put distrust before trust with this woman, then. He needed a clear eye and a clear head in the worrisome days to come.

For worrisome they would be. As they rode east along the river, the silence grew deeper, as if the very trees themselves held their breath. There was more behind this early winter than a foible of nature. Beneath it a sense of huge power thrummed, a power that had more than once raised the hairs on the back of his neck.

He could not yet say that it would endure, nor even guess what it might do. But ancient magicks were stirring, and his every sense was on alert to detect anything out of the ordinary. Somehow he recognized that thrum of power, that echo of immeasurable forces at work, though he could not say he knew it.

But he recognized it anyway, in the way the tips of his fingers would tingle and the hairs at his nape stand on end. He knew it in the way the pit of his stomach responded to it. He had met this force before.

The attack on the caravan had been abnormal. Of that there was no doubt. He’d seen such things before, but rarely did more than a few die, and never were the riches left behind. As near as he could tell, nothing had been stolen.

Which meant the attack was directed at a person or group of people. That it was born of vengeance, or something even darker. But it was not a robbery.

He wondered if anyone coming with him even guessed at the kind of darkness that was approaching, or if he and his two Anari friends were the only ones.

Somehow the woman Tess had escaped the massacre. And Giri was right. That alone, given the savagery of the attack, was cause for wonder and doubt.

“Is something wrong?” she asked him now.

He realized his silence had endured too long. “Nothing,” he answered, though it was far from true. “I’m going to drop back and check on the rest of the column.”

She nodded and returned her attention forward.

Column? Ragtag bunch of merchants, farmers and youths from Whitewater. He daren’t let them become at all separated, for he doubted any of them knew how to fight. Defense would be all on him and the Anari.

He knew his skills and those of his two companions, and never doubted they could do the job, but ’twere still far better if they encountered no one at all.

Because they had to follow the trade road along the river, and because they were so many, most unaccustomed to riding over difficult ground, they neared their destination too late to hope for a return before dark. They would have to spend the night.

Archer looked up at the still-blue sky as the shadows deepened around them, knowing the sun had already fallen behind the mountains. Noting, with a sense of uneasiness approaching alarm, that no vultures circled in the sky overhead.

That could mean only one thing: someone was already searching among the remains of the caravan.

He halted the column and gave a whistle that sounded like a birdcall. Once such a sound would have seemed normal in these woods. Now, with no wildlife left to be found, it sounded both eerie and obvious.

Moments later, Giri, then Ratha, emerged seamlessly from the shadows, joining him.

“No vultures,” said Archer. “Is someone at the caravan?”

Ratha shook his head. “Not a soul for leagues around us.”

“So even the vultures have fled.”

“Everything has fled,” Giri said. “Nothing stirs in these woods any longer, not bird, not squirrel, not deer nor boar.”

“It wasn’t like that just yesterday,” Archer remarked. Though there had been a paucity of life, they had still caught sight of the occasional squirrel and bird.

“No, ’tis far worse today,” Ratha replied. “There is something foul afoot.”

With that Archer agreed. “Did you make it as far as the caravan?”

“Aye,” Giri answered. “Naught has changed. All is frozen as if in ice.”

“Best we camp here,” Archer decided. “We’ll rescue what we can in the morning.”

There was some grumbling in response to his decision, though he couldn’t blame anyone for it. None had really expected to have to spend the night in the abandoned woods, though he had warned them they probably would.

Or perhaps they grumbled because the woods and the riverbank felt so…strange. As if they had left everything familiar behind and stepped into a different world where the threats were unknown.

As Archer guided the establishment of the camp, he mulled that over. He could only conclude that somehow, someway, they had indeed stepped out of the familiar.

And he had a terrible feeling that it would be a long time before they could go back.

6

Tom was at last enjoying the adventure he’d always longed for, and he wasn’t about to let anything ruin it. In fact, he was quite delighted that everyone seemed so uneasy because the forest was empty of its normal inhabitants.

Actually he was quite glad to know they wouldn’t run into any boar or bears, and if that meant doing without deer and birds, he was content. He’d never slept outdoors in his life, and cold though this night was, the big fire they’d built cast both light and warmth, and provided yet another opportunity for the men of Whitewater to swap tall tales.

But he first had a mission. Carrying a carriage blanket made of fleece, he approached the Lady Tess. “Lady,” he said awkwardly, “Sara sent this blanket and asked me to give it to you for the night.”

The woman, who looked so alone and uncertain amidst the crowd of strangers, gave him a smile that made him feel at least six feet tall. “Thank you,” she said, allowing him to spread it over her. “How kind of you and Sara.”

“Thank Sara,” he said, shuffling his feet awkwardly. “’Twas she who thought of it.”

“And you who carried it and gave it to me. I thank you, too. I’m afraid I don’t know your name.”

“Tom. Tom Downey, the gatekeeper’s son. Most call me Young Tom.”

“Well, Young Tom Downey, I am pleased to make your acquaintance. I’m Tess.” A flicker of memory flashed into her mind; the memory of a mockingbird in the morning. “Tess Birdsong.”

He smiled bashfully. “Would you like something warm to drink? There’s tea, and some mulled cider.”

“Cider sounds wonderful.”

Many of the men had brought skins of hard cider with them, a remedy against the cold, and Tom, thanks to Sara, had brought spices and a pot in which to heat it. Sara, in fact, was responsible for the fact that the party had eaten a hot meal this night. Tom’s packhorse had been loaded, unlike the others, with viands and some cooking pots, with the result that he had been something of a hero a little while ago, as he’d cooked and served a meal they otherwise would have done without, relying instead on the strips of dried fish and jerky most had packed.

And now he could give the lady a tin cup full of piping hot mulled cider. She accepted it gratefully and held it close, as if savoring the warmth. She patted the ground beside her. “Tell me about yourself, Young Tom.”

He sat, but felt nearly tongue-tied. “There’s naught to tell,” he said, when he could find his voice again. The woman was so beautiful and otherworldly, and he wasn’t accustomed to conversing with strangers, especially beautiful ones.

“Ah, you must have done something during your years,” she replied.

“Nothing of interest. My dad is the town gatekeeper. Mostly I help him.”

“That’s a very important job.”

“I suppose.”

She smiled gently. “But you long for greater adventures?”