По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

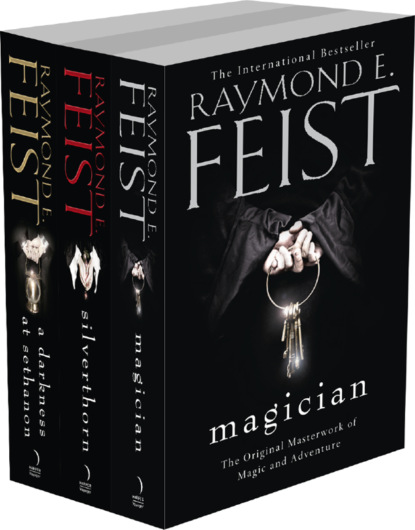

The Riftwar Saga Series Books 2 and 3: Silverthorn, A Darkness at Sethanon

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Dolgan looked at Borric. ‘No one has ever conquered our highland villages, not in the longest memory of the dwarven folk. But it would prove an irritation for someone to try. The dwarves will stand with the Kingdom, Your Lordship. You have long been a friend to us, trading fairly and giving aid when asked. And we have never run from battle when we were called.’

Arutha said, ‘And what of Stone Mountain?’

Dolgan laughed. ‘I thank His Highness for the jog to my memory. Old Harthorn and his clans would be sorely troubled should a good fight come and they were not invited. I’ll send runners to Stone Mountain as well.’

Pug and Tomas watched while the Duke wrote messages to Lyam and Fannon, then full stomachs and fatigue began to lull them, despite their long sleep. The dwarves gave them the loan of heavy cloaks, which they wrapped about pine boughs to make comfortable mattresses. Occasionally Pug would turn in the night, coming out of his deep sleep, and hear voices speaking low. More than once he heard the name Mac Mordain Cadal.

Dolgan led the Duke’s party along the rocky foothills of the Grey Towers. They had left at first light, the dwarven chieftain’s sons departing for their own destinations with their men. Dolgan walked before the Duke and his son, followed by the puffing Kulgan and the boys. Five soldiers of Crydee, those still able to continue, under the supervision of Sergeant Gardan followed behind, leading two mules. Walking behind the struggling magician, Pug said, ‘Kulgan, ask for a rest. You’re all done in.’

The magician said, ‘No, boy, I’ll be all right. Once into the mines, the pace will slow, and we should be there soon.’

Tomas regarded the stocky figure of Dolgan, marching along at the head of the party, short legs striding along, setting a rugged pace. ‘Doesn’t he ever tire?’

Kulgan shook his head. ‘The dwarven folk are renowned for their strong constitutions. At the Battle of Carse Keep, when the castle was nearly taken by the Dark Brotherhood, the dwarves of Stone Mountain and the Grey Towers were on the march to aid the besieged. A messenger carried the news of the castle’s imminent fall, and the dwarves ran for a day and a night and half a day again to fall on the Brotherhood from behind without any lessening of their fighting ability. The Brotherhood was broken, never again organizing under a single leader.’ He panted a bit. ‘There was no idle boasting in Dolgan’s appraisal of the aid forthcoming from the dwarves, for they are undoubtedly the finest fighters in the West. While they have few numbers compared to men, only the Hadati hillmen come close to their equal as mountain fighters.’

Pug and Tomas looked with newfound respect upon the dwarf as he strode along. While the pace was brisk, the meal of the night before and another this morning had restored the flagging energies of the boys, and they were not pushed to keep up.

They came to the mine entrance, overgrown with brush. The soldiers cleared it away, revealing a wide, low tunnel. Dolgan turned to the company. ‘You might have to duck a bit here and there, but many a mule has been led through here by dwarven miners. There should be ample room.’

Pug smiled. The dwarves proved taller than tales had led him to expect, averaging about four and a half to five feet tall. Except for being short-legged and broad-shouldered, they looked much like other people. It was going to be a tight fit for the Duke and Gardan, but Pug was only a few inches taller than the dwarf, so he’d manage.

Gardan ordered torches lit, and when the party was ready, Dolgan led them into the mine. As they entered the gloom of the tunnel, the dwarf said, ‘Keep alert, for only the gods know what is living in these tunnels. We should not be troubled, but it is best to be cautious.’

Pug entered and, as the gloom enveloped him, looked over his shoulder. He saw Gardan outlined against the receding light. For a brief instant he thought of Carline, and Roland, then wondered how she could seem so far removed so quickly, or how indifferent he was to his rival’s attentions. He shook his head, and his gaze returned to the dark tunnel ahead.

The tunnels were damp. Every once in a while they would pass a tunnel branching off to one side or the other. Pug peered down each as he passed, but they were quickly swallowed up in gloom. The torches sent flickering shadows dancing on the walls, expanding and contracting as they moved closer or farther from each other, or as the ceiling rose or fell. At several places they had to pull the mules’ heads down, but for most of their passage there was ample room.

Pug heard Tomas, who walked in front of him, mutter, ‘I’d not want to stray down here; I’ve lost all sense of direction.’ Pug said nothing, for the mines had an oppressive feeling to him.

After some time they came to a large cavern with several tunnels leading out. The column halted, and the Duke ordered watches to be posted. Torches were wedged in the rocks and the mules watered. Pug and Tomas stood with the last watch, and Pug thought a hundred times that shapes moved just outside the fire’s glow. Soon guards came to replace them, and the boys joined the others, who were eating. They were given dried meat and biscuits to eat. Tomas asked Dolgan, ‘What place is this?’

The dwarf puffed on his pipe. ‘It is a glory hole, laddie. When my people mined this area, we fashioned many such places. When great runs of iron, gold, silver, and other metals would come together, many tunnels would be joined. And as the metals were taken out, these caverns would be formed. There are natural ones down here as large, but the look of them is different. They have great spires of stone rising from the floor, and others hanging from the ceiling, unlike this one. You’ll see one as we pass through.’

Tomas looked above him. ‘How high does it go?’

Dolgan looked up. ‘I can’t rightly say. Perhaps a hundred feet, perhaps two or three times as much. These mountains are rich with metals still, but when my grandfather’s grandfather first mined here, the metal was rich beyond imagining. There are hundreds of tunnels throughout these mountains, with many levels upward and downward from here. Through that tunnel there’ – he pointed to another on the same level as the floor of the glory hole – ‘lies a tunnel that will join with another tunnel, then yet another. Follow that one, and you’ll end up in the Mac Bronin Alroth, another abandoned mine. Beyond that you could make your way to the Mac Owyn Dur, where several of my people would be inquiring how you managed entrance into their gold mine.’ He laughed. ‘Though I doubt you could find the way, unless you were dwarven born.’

He puffed at his pipe, and the balance of the guards came over to eat. Dolgan said, ‘Well, we had best be on our way.’

Tomas looked startled. ‘I thought we were stopping for the night.’

‘The sun is yet high in the sky, laddie. There’s half the day left before we sleep.’

‘But I thought …’

‘I know. It is easy to lose track of time down here, unless you have the knack of it.’

They gathered together their gear and started off again. After more walking they entered a series of twisting, turning passages that seemed to slant down. Dolgan explained that the entrance on the east side of the mountains was several hundred feet lower than on the west, and they would be moving downward most of the journey.

Later they passed through another of the glory holes, smaller than the last, but still impressive for the number of tunnels leading from it. Dolgan picked one with no hesitation and led them through.

Soon they could hear the sound of water, coming from ahead. Dolgan said, over his shoulder, ‘You’ll soon see a sight that no man living and few dwarves have ever seen.’

As they walked, the sound of rushing water became louder. They entered another cavern, this one natural and larger than the first by several times. The tunnel they had been walking in became a ledge, twenty feet wide, that ran along the right side of the cavern. They all peered over the edge and could see nothing but darkness stretching away below.

The path rounded a curve in the wall, and when they passed around it, they were greeted with a sight that made them all gasp. Across the cavern, a mighty waterfall spilled over a huge outcropping of stone. From fully three hundred feet above where they stood, it poured into the cavern, crashing down the stone face of the opposite wall to disappear into the darkness below. It filled the cavern with reverberations that made it impossible to hear it striking bottom, confounding any attempt to judge the fall’s height. Throughout the cascade luminous colors danced, aglow with an inner light. Reds, golds, greens, blues, and yellows played among the white foam, falling along the wall, blazing with brief flashes of intense luminosity where the water struck the wall, painting a fairy picture in the darkness.

Dolgan shouted over the roar, ‘Ages ago the river Wynn-Ula ran from the Grey Towers to the Bitter Sea. A great quake opened a fissure under the river, and now it falls into a mighty underground lake below. As it runs through the rocks, it picks up the minerals that give it its glowing colors.’ They stood quietly for a while, marveling at the sight of the falls of Mac Mordain Cadal.

The Duke signaled for the march to resume, and they moved on. Besides the spectacle of the falls, they had been refreshed by spray and cool wind off them, for the caverns were dank and musty. Onward they went, deeper into the mines, past numberless tunnels and passages. After a time, Gardan asked the boys how they fared. Pug and Tomas both answered that they were fine, though tired.

Later they came to yet another cavern, and Dolgan said it was time to rest the night. More torches were lit, and the Duke said, ‘I hope we have enough brands to last the journey. They burn quickly.’

Dolgan said, ‘Give me a few men, and I will fetch some old timbers for a fire. There are many lying about if you know where to find them without bringing the ceiling down upon your head.’

Gardan and two other men followed the dwarf into a side tunnel, while the others unloaded the mules and staked them out. They were given water from the waterskins and a small portion of grain carried for the times when they could not graze.

Borric sat next to Kulgan. ‘I have had an ill feeling for the last few hours. Is it my imagining, or does something about this place bode evil?’

Kulgan nodded as Arutha joined them. ‘I have felt something also, but it comes and goes. It is nothing I can put a name to.’

Arutha hunkered down and used his dagger to draw aimlessly in the dirt. ‘This place would give anyone a case of the jumping fits and starts. Perhaps we all feel the same thing: dread at being where men do not belong.’

The Duke said, ‘I hope that is all it is. This would be a poor place to fight’ – he paused – ‘or flee from.’ The boys stood watch, but could overhear the conversation, as could the other men, for no one else was speaking in the cavern and the sound carried well. Pug said in a hushed voice, ‘I will also be glad to be done with this mine.’

Tomas grinned in the torchlight, his face set in an evil leer. ‘Afraid of the dark, little boy?’

Pug snorted. ‘No more than you, should you but admit it. Do you think you could find your way out?’

Tomas lost his smile. Further conversation was interrupted by the return of Dolgan and the others. They carried a good supply of broken timbers, used to shore up the passages in days gone by. A fire was quickly made from the old, dry wood, and soon the cavern was brightly lit.

The boys were relieved of guard duty and ate. As soon as they were done eating, they spread their cloaks. Pug found the hard dirt floor uncomfortable, but he was very tired, and sleep soon overtook him.

They led the mules deeper into the mines, the animal’s hooves clattering on the stone, the sound echoing down the dark tunnels. They had walked the entire day, taking only a short rest to eat at noon. Now they were approaching the cavern where Dolgan said they were to spend their second night. Pug felt a strange sensation, as if remembering a cold chill. It had touched him several times over the last hour, and he was worried. Each time he had turned to look behind him. This time Gardan said, ‘I feel it too, boy, as if something is near.’

They entered another large glory hole, and Dolgan stood with his hand upraised. All movement ceased as the dwarf listened for something. Pug and Tomas strained to hear as well, but no sounds came to them. Finally the dwarf said, ‘For a time I thought I heard … but then I guess not. We will camp here.’ They had carried spare timber with them and used it to make a fire.

When Pug and Tomas left their watch, they found a subdued party around the fire. Dolgan was saying, ‘This part of Mac Mordain Cadal is closest to the deeper, ancient tunnels. The next cavern we come to will have several that lead directly to the old mines. Once past that cavern, we will have a speedy passage to the surface. We should be out of the mine by midday tomorrow.’

Borric looked around. ‘This place may suit your nature, dwarf, but I will be glad to have it behind.’

Dolgan laughed, the rich, hearty sound echoing off the cavern walls. ‘It is not that the place suits my nature, Lord Borric, but rather that my nature suits the place. I can travel easily under the mountains, and my folk have ever been miners. But as to choice, I would rather spend my time in the high pastures of Caldara tending my herd, or sit in the long hall with my brethren, drinking ale and singing ballads.’

Pug asked, ‘Do you spend much time singing ballads?’

Dolgan fixed him with a friendly smile, his eyes shining in the firelight. ‘Aye. For winters are long and hard in the mountains. Once the herds are safely in winter pasture, there is little to do, so we sing our songs and drink autumn ale, and wait for spring. It is a good life.’

Pug nodded. ‘I would like to see your village sometime, Dolgan.’