По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

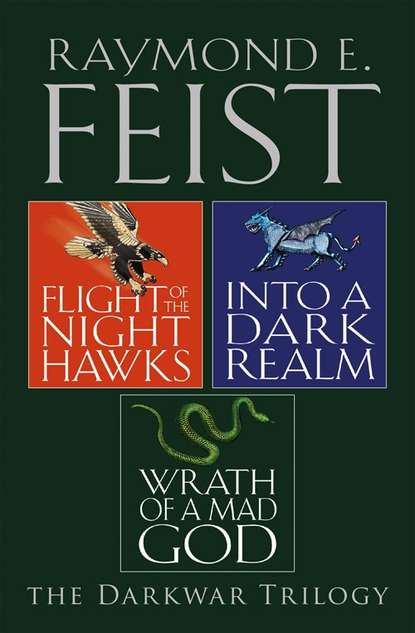

The Complete Darkwar Trilogy: Flight of the Night Hawks, Into a Dark Realm, Wrath of a Mad God

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Amafi relayed Kaspar’s message to Tal, who said, ‘If we are separated and questioned, you know what to say.’

‘Yes, Magnificence,’ replied the grey-haired assassin. ‘You have met the Comté on a number of occasions in Bas-Tyra and elsewhere. You have even played cards with him, and you were pleased to discover yourselves travelling on the same boat from Caralién to Kesh. We travelled by land from Pointer’s Head to Ishlana, then by river boat. The Comté said he had come from Rillanon, so I assume he came by land from Deep Taunton to Jonril then by boat to Caralién. It was a most fortuitous happenstance as the Comté is convivial company.’ With an evil smile, he added, ‘And an indifferent card player.’

‘Don’t overdo it,’ said Tal. ‘But if they assume I’m staying close to him to cheat him at cards, they will perhaps not suspect that we are plotting together.’

‘A small bad intention is often far more easily believed than a big one, Magnificence,’ whispered Amafi. ‘Once I avoided the gallows by merely claiming to have entered a certain house to have a dalliance with the man’s wife instead of attempting to kill him. The woman vigorously denied it, but the odd thing was, the louder she claimed it wasn’t so, the more the authorities believed it was. I was put in a cell, from which I escaped a few days later; the man beat his wife, causing her brother to kill him in a duel, and I collected my fee for the man’s death, despite the fact I had not placed one finger upon him. I did, however, revisit the wife to console her, and found her behaviour clearly demonstrated why the constables were inclined to believe me and not her.’ With a half-wistful look, he added, ‘Grief made her ardent.’

Tal chuckled. There had been several times in their relationship when he would have happily murdered Amafi, and he was certain there had been more than one occasion when the former assassin would have killed him for the right price, but at some odd point along the way he had become fond of the rogue.

His feelings for Kaspar were a great deal more complex. The man had been responsible for the wholesale destruction of his entire people, and but for a freak act of fate Tal Hawkins, once Talon of the Silver Hawk, would have been dead along with the majority of the Orosini.

Yet Kaspar was now an ally, another agent working for the Conclave of Shadows. And Tal understood how many of Kaspar’s murderous decisions had been made under the influence of the Conclave’s most dangerous enemy, the magician named Leso Varen. Yet even without Varen’s influence, Kaspar could be a cold-hearted, unforgiving bastard. Yet even when he had served Kaspar with the intent of betraying him to revenge his people, there was something about Kaspar Tal admired. He found himself in the confusing situation of knowing he would give his life to save Kaspar against their common enemies, but that in other circumstances, he would happily kill the man.

‘You look lost in thought, Magnificence. Is something troubling you?’

‘Nothing more than the usual, Amafi. I find the gods have an evil sense of humour, sometimes.’

‘That is true, Magnificence. My father, an occasionally wise man, once said that we were blessed only when the gods remained ignorant of us.’

Tal’s gaze returned to Kaspar. ‘Something’s happening.’

Amafi turned to see a minor court official speaking to Kaspar, and after a moment, Kaspar and Pasko followed him through the small side door Kaspar had mentioned to Amafi. Tal sighed. ‘Well, now we shall see if our plans fall apart before they begin.’

‘Let us hope the gods are ignoring us today, Magnificence.’

Kaspar was led by a very polite functionary through a long series of corridors. He was taken by side passages around the smaller reception hall used for greeting visiting dignitaries towards the suite of offices reserved for the higher ranking government officials.

The palace of the Emperor occupied the entire upper half of a great plateau that overlooked the Overn Deep and the lower city at the foot of the tableland. Ages before, Keshian rulers had constructed a massive fortress on top of this prominence, a highly defensible position to protect their small city below. Over the centuries the original fortress had been added to, reconstructed and expanded, until the entire top of the plateau was covered. Tunnels extended down into the soil, some leading into the lower city. It was like nothing so much as a hive, Kaspar thought. And as a result he rarely knew where he was. Of course, before this particular journey he never had to worry about getting lost, because as a visiting ruler, he had always had an attentive Keshian noble or bureaucrat to see to his needs.

Kaspar understood the organization of the Keshian government as well as any foreigner could, and he knew that this nation, more than any other on Midkemia, was controlled by bureaucracy, a system that had endured longer than any ruling dynasty. Kings might give edicts and princes command armies, but if the edicts were not handed down to the populace no one obeyed them, and if orders to move food and supplies around weren’t forthcoming, the prince’s army quickly starved to death in the field, or mutinied.

On more than one occasion, Kaspar had been thankful his duchy was relatively small and tidy by comparison. He could name every functionary in the citadel that had served as his home for most of his life. Here he doubted the Emperor could name even those servants who worked in his personal apartment.

They reached a large office, and Pasko was instructed to wait on a stone bench outside. Kaspar was motioned through a door into an even larger room, one that was an odd mix of opulence and functionality. In the middle of the room sat a large table, behind which rested a man on a chair. Once powerful, he had gone to fat, though there was still ample muscle under that fat. Kaspar knew that there was a shrewd and dangerous mind in that old man’s head. He wore the traditional garb of a Trueblood: a linen kilt around his hips bound by a woven silk belt, cross-gartered sandals on his feet, and a bare chest. He also wore an impressive array of jewellery, mostly gold and gems, though there were some interesting polished stones among the dozen or so chains he had around his neck. These stood in stark contrast against his night-black skin. He regarded Kaspar with eyes so dark brown they looked sable, and then he smiled, his white teeth dramatic in contrast to his face.

‘Kaspar,’ he said in a friendly tone. ‘You look different, my friend. I’d say better, if you think that not overstepping the mark.’ He waved the escort outside, then with a motion of his hand ordered the two guards by the door to go as well, leaving Kaspar alone with him.

Kaspar nodded slightly. ‘Turgan Bey, Lord of the Keep, why am I not surprised?’

‘You seriously didn’t think the former Duke of Olasko could sneak into the Empire without our notice, did you?’

‘One can hope,’ said Kaspar.

Lord Turgan indicated that Kaspar should take a seat. ‘Comté Andre?’ He looked at something written on a piece of parchment. ‘I must confess it took a great deal of self-control not to have you picked up at the border, but I was interested in seeing just what you were up to. Had you sneaked into the city or met with known insurgents or smugglers this would all make sense. But instead you submit a petition to present yourself as a trade envoy plenipotentiary from the Duke of Bas-Tyra’s court? And then you walk in here and stand around like … like I don’t know what.’

The still-powerful-looking old man drummed his fingers on the desk for a moment, then added, ‘So, if you have a reason why I shouldn’t throw you and that servant of yours into the Overn to feed the crocodiles I’d love to hear it. Maybe I’ll toss in your friend Hawkins as well.’

Kaspar sat back. ‘Hawkins and I play cards, and I think he cheats. Nothing more. I thought perhaps arriving with a famous squire of the Kingdom might give me a little more credibility.’

‘Or get the youngster killed before his time.’ Turgan Bey chuckled. ‘You think for a minute I don’t know that Talwin Hawkins was in your service for over two years? Or that I don’t know he was key to your overthrow? But here you are, in my own keep acting as if you’re casual travellers idling the time away with meaningless card games.’ He shook his head. ‘I can’t say that I hold you in any affection, Kaspar. You’ve always been someone we watched because of all the mischief you caused, but as long as you confined yourself to your own little corner of the world, we didn’t much care. And, to be fair, you’ve always honoured your treaties with Kesh.

‘But as you are no longer ruler of Olasko, certain political niceties need no longer be observed. And since you’re attempting to enter the palace under a false identity, can we safely assume you’re a spy?’

‘You may,’ said Kaspar with a smile. ‘And I have something for you.’ He reached into his tunic and pulled out the black Nighthawk amulet. He slid it across the table to Turgan and waited while the old minister picked it up and examined it.

‘Where did you get this?’

‘From a friend of a friend, who got it from Lord Erik von Darkmoor.’

‘That’s a name to make a Keshian general lose sleep. He’s cost us dearly a couple of times at the border.’

‘Well, if your frontier commanders didn’t get the urge to conquer in the name of their Emperor without instruction from your central authority, you’d have less problems with von Darkmoor.’

‘We don’t necessarily send our brightest officers to the western frontier,’ Turgan Bey sighed. ‘We save those to build up our own factions here in the capital. Politics will be the death of me yet.’ He tapped his finger on the amulet. ‘What do you make of this?’

‘Keshian nobles are dying.’

‘That happens a lot,’ said Turgan Bey with a smile. ‘We have a lot of nobles. You can’t toss a barley cake from a vendor’s cart in the lower city without hitting a noble. Comes from having a vigorous breeding population for several thousand years.’

‘Truebloods are dying, too.’

Turgan Bey lost his smile. ‘That should not have been apparent to von Darkmoor. He must have better spies than I gave him credit for. Now, this still leads me to wonder why the former Duke of Olasko has wandered into my city, into my very palace, to hand me this. Who sent you? Duke Rodoski?’

‘Hardly,’ said Kaspar. ‘My brother-in-law would just as soon see my head adorn the drawbridge leading into his citadel as he would see it across the dinner table. Only his love for my sister keeps it on my shoulders; that and staying far away from Olasko.’

‘Then von Darkmoor sent you?’ said Bey, his brow furrowing.

‘I’ve only met the esteemed Knight-Marshal of Krondor once, some years ago, and then we spoke only for a moment.’

Bey’s gaze narrowed. ‘Who sent you, Kaspar?’

‘One who reminds you that not only enemies hide in shadows,’ said Kaspar.

Turgan Bey stood up and said, ‘Come with me.’

He led Kaspar though a chamber that appeared to be a more comfortable working area with a pair of writing desks for scribes, as well as a large divan chair which could comfortably accommodate him. He motioned Kaspar to step out onto a balcony overlooking a lush garden three storeys below and at last said, ‘Now I can be certain no one is listening.’

‘You don’t trust your own guards?’

‘I do, but when members of the Imperial family, no matter how distantly related they may be, start turning up dead, I don’t trust anyone.’ He glanced at Kaspar. ‘Nakor sent you?’

‘Indirectly,’ said Kaspar.

‘My father told me the story of the first time that crazy Isalani showed up in the palace. He and the Princes Borric and Erland, as well as Lord James – he was a baronet or baron back then I believe – kept the Empress alive and arranged it so that Diigai would sit upon the throne after her by marrying her granddaughter to him. They defended her in the very Imperial throne room! Against murderers who wished to put that fool Awari on the throne. From that day forward my father had a different attitude towards the Kingdom. And he told the story of how Nakor pulled that hawk from his bag and restored the mews here in the palace.’ Leaning back, he added, ‘It was a remarkable day. So you can imagine my surprise the first time Nakor turned up at my father’s estate up in Geansharna – I must have been about fifteen years old.’ His eyes narrowed. ‘That crazy Isalani has been surprising me ever since. I won’t ask how you came to work with him, but if he’s sent you, there must be good reason.’

‘There is. I had in my employ, or so I thought, a magician by the name of Leso Varen. It turns out he was partially to blame for some of my excesses over the last few years before I was exiled.’

Bey began to speak, thought better of it, and Kaspar continued. ‘If at some point you’d care to listen to a detailed appraisal of what I did and why, I’ll burden you with it, but for now suffice it to say that Varen may be at the centre of your current troubles, and if that is true, then there is more at risk than merely a bloodier-than-usual game of Keshian politics.