По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

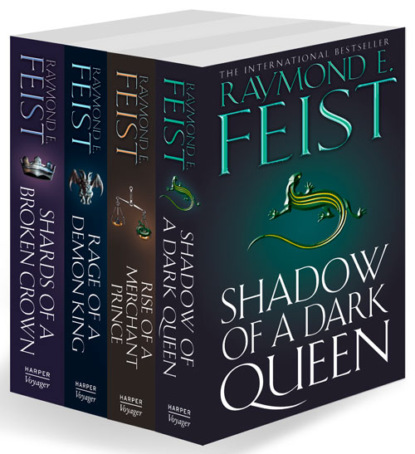

The Serpentwar Saga: The Complete 4-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Roo fell backwards, hard against the wagon’s tailgate, and barely kept himself from falling. He leaned down, got his arms under the body’s arms, and heaved.

‘You’re no good to me, boy!’ bellowed de Loungville. ‘If you don’t get him in that wagon by the time I count to ten, you worthless slug, I’ll cut your heart out before your eyes! One!’

Roo heaved and his face betrayed panic. ‘Two!’ He forced his own weight forward, and got the corpse sitting up. ‘Three!’

He lifted with his legs and somehow got himself half turned around, so that the dead man rested against the tailgate. ‘Four!’ Roo took a breath and heaved again, and suddenly the man was halfway into the wagon. ‘Five!’ Roo let the body go and reached down quickly, gripping the corpse around the hips. He ignored the reek of urine and feces as he heaved with his last reserve of strength. Then he collapsed.

‘Six!’ screamed de Loungville, leaning over the boy, who sat at the base of the wagon.

Roo looked up and saw the man’s legs were hanging over the end of the tailgate. He struggled to his feet as de Loungville shouted, ‘Seven!’ and pushed as hard on the legs as he could.

They bent and he half pushed, half rolled the dead man all the way into the wagon as de Loungville reached the count of eight.

Then he fainted.

Erik took a step forward. De Loungville turned, took a single step, and delivered a backhanded blow to Erik that brought him to his knees. Lowering his head to lock gazes with the stunned Erik, Robert de Loungville said, ‘You will learn, dog meat, that no matter what happens to your friends, you will do what you’re told when you are told and nothing else. If that’s not the first thing you learn, you’ll be crow bait before the sun sets.’

Straightening up, he shouted, ‘Get them back to their cell!’

The still-stunned men moved raggedly along, not certain what had happened. Erik’s ears rang from the blow to his head, but he risked a glance back at Roo and saw that two guards had picked him up and were bringing him along.

In silence the men were taken back to the death cell and herded in. Roo was unceremoniously tossed in, and the door slammed shut behind.

The man from Kesh, Sho Pi, came to look at Roo and said, ‘He’ll recover. It is mostly shock and fear.’

Then he turned to Erik and smiled, a dangerous look around his eyes. ‘Didn’t I tell you it might be something else?’

‘But what?’ asked Biggo. ‘What was all this vicious mummery?’

The Keshian sat down, crossing his legs before him. ‘It was what is called an object lesson. This man de Loungville, who works, I imagine, for the Prince, he wishes you to know something without any doubt whatsoever.’

‘Know what?’ asked Billy Goodwin, a slender fellow with curly brown hair.

‘He wants you to know that he will kill you without hesitation if you do not do what he wants.’

‘But what does he want?’ asked the man whose name Erik didn’t know, a thin man with a grey beard and red hair.

Closing his eyes as if he were about to take a rest, Sho Pi said, ‘I do not know, but I think it will be interesting.’

Erik sat back and suddenly giggled.

Biggo said, ‘What is it?’

Finding himself embarrassed before these men, he said, ‘I loaded my pants.’ Then he started to laugh, and the laughter had a hysterical edge to it.

Billy Goodwin said, ‘I dirtied myself, too.’

Erik nodded, and suddenly the laughter was gone and he found to his amazement he was crying. His mother would be so angry with him if she found out.

Roo roused when food appeared, and to their astonishment it was not only abundant but good. Before, they had gotten a vegetable stew in a heavy beef stock, but now they were served steaming vegetables and slabs of bread, heavy with butter, and cheese and meat. Rather than the usual bucket of water, there were cold pewter mugs, and a large pitcher of chilled white wine – enough to slake thirst and ease the tension, but not enough to get anyone drunk. They ate and considered their fortune.

‘Do you think this is some cruel thing the Prince is doing to us?’ asked the grey-bearded man, a Rodezian named Luis de Savona.

Biggo shook his head. ‘I’m a fair judge of men. That Robert de Loungville could be cruel like this if it suited his needs, but the Prince isn’t that sort of man, I’m thinking. No, like our Keshian friend here says –’

‘Isalani,’ corrected Sho Pi. ‘We live in the Empire, but we are not Keshian.’

‘Whatever,’ said Biggo. ‘What he said about this being a lesson is right. That’s why we still have these on.’ He flipped the length of rope that still hung from around his neck. ‘To remind us we’re officially dead. So that whatever happens next, we know that we’re living on sufferance.’

Billy Goodwin said, ‘I don’t think they’ll have to remind me anytime soon.’ He shook his head. ‘Gods, I can’t remember what I was thinking when they kicked the box from under me. I was a baby again and waiting for my mum to come fetch me from some difficulty. I don’t think I can tell what I felt like.’

The others nodded. Erik felt tears start to gather as he remembered his own feelings as he fell. Pushing that aside, he turned to Roo. ‘How are you doing?’

Roo said nothing, only nodded as he ate.

Erik knew he was looking at something powerful changing in his friend, something was marking him and making him different from what he had known all his life in Ravensburg. He wondered if he was changing as much as his friend.

Guards arrived later to remove the trays and pitchers, and no one spoke. Soon the cells fell into darkness, and the single torch that illuminated the hall outside remained unlit.

‘I think it’s de Loungville’s way of telling us to sleep as soon as we can,’ said Biggo.

Sho Pi nodded. ‘We will get an early start on whatever it is we do tomorrow, then.’ He curled up on the stone shelf and closed his eyes.

Erik said, ‘I’m not sleeping in my own filth.’ He removed his boots and trousers, then took them to the slops bucket and did his best to shake loose the dirt there, using a bit of the drinking water to clean them as best he could. It was a gesture, nothing more, and the pants were still dirty and again wet when he put them back on, but he felt better for trying.

Some others followed his example, as Erik nodded at Roo, who sank back into a corner with his arms wrapped around him, despite the fact it wasn’t at all cold that night. But Erik knew his friend felt a chill inside that no fire would ever drive out.

Erik lay back, and to his astonishment felt a warm fatigue sink into his bones, and before he could ponder the amazing events of the day he was asleep.

‘Get up, you scum!’ shouted de Loungville, and the prisoners stirred. Suddenly the cell erupted in a cacophony of sound as guards slammed shields against the iron bars and began to shout.

‘Get up!’

‘On your feet!’

Erik was standing before he was fully awake. He looked at Roo, who blinked like an owl caught in a lantern’s light.

The door to the cell was opened and the men ordered out. They came to stand in the same order they had marched to the gibbet in, and waited without comment.

‘When I give you the command to right turn, you will all turn as one and face that door. Understand?’ The last word wasn’t a question but a harsh command.

‘Right turn!’

The men turned, feet shuffling, the shackles making any quick movement difficult. The door at the end of the cell block opened, and de Loungville said, ‘When I give the order, you will start forward, with your left foot, and you will march behind that soldier there.’ He pointed to a guardsman with the chevron of a corporal on his helm. ‘You will follow him in order, and any man who fails to keep his place will be back on the gallows within one minute. Are we clear on that?’

The men shouted, ‘Yes, Sergeant de Loungville!’

‘March!’