По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

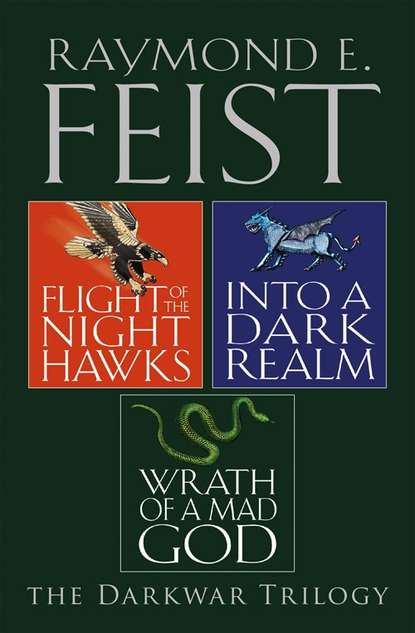

The Complete Darkwar Trilogy: Flight of the Night Hawks, Into a Dark Realm, Wrath of a Mad God

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

A few minutes later he found Bek sitting under a tree watching some students listen to Rosenvar lecture. When he saw Nakor approach, he jumped to his feet and said, ‘Are we leaving?’

‘Why, are you bored?’

‘Very. I have no idea what that old man is talking about. And the students here are not very friendly.’ He looked at Nakor and said accusingly, ‘And that thing you did in my head …’ His expression was one of frustration verging on tears. ‘One of the boys insulted me and normally I would have just hit him very hard, probably in the face. And if he had gotten up, I’d have hit him again. I’d have kept on hitting him until he didn’t get up.’ With an almost pained expression, Bek said, ‘But I couldn’t, Nakor. I couldn’t even ball my fist. He just stood there looking at me like there was something wrong with me, and there was! And then there was this pretty girl I wanted, but when she wouldn’t stop to talk to me and I tried to grab her, the same damn thing happened! I couldn’t bring my hand up to—’ Bek looked as if he were on the verge of tears. ‘What did you do to me, Nakor?’

Nakor put his hand on the large youngster’s shoulder and said, ‘Something I would rather not do to anyone, Bek. At least for a while, you can’t do harm to someone else except if you’re defending yourself.’

Bek sighed. ‘Am I always going to be this way?’

‘No,’ said Nakor. ‘Not if you learn to control your own impulses and anger.’

Bek laughed. ‘I never get angry, Nakor. Not really.’

Nakor motioned for Bek to sit and sat next to him. ‘What do you mean?’

Bek shrugged. ‘Sometimes I get annoyed, and if I’m in pain I can really break things up, but I find most things either funny or not funny. People talk about love, hate, envy and the rest of it, and I think I know what they’re talking about, but I’m not certain.

‘I mean, I’ve seen how people act around each other and I sort of remember feeling things when I was really little, like the way it felt when my mother held me. But mostly I don’t care about the same things that other people care about.’ He looked at Nakor and there was almost a pleading quality to his expression, ‘I often thought that I was different, Nakor. Many people have told me I am.

‘And I’ve never cared about that.’ He lowered his head, looking at the ground. ‘But this thing you’ve done to me, it makes me feel—’

‘Frustrated?’

Bek nodded. ‘I can’t … do things like I used to. I wanted that girl, Nakor. I don’t like not being able to have what I want!’ He looked Nakor in the face and the little gambler could see tears of frustration forming in Bek’s eyes.

‘You’ve never had anyone say no to you, have you?’

‘Sometimes, but if they do I kill them and take what I want, anyway.’

Nakor was silent, then he thought of something. ‘Someone once told me a story about a man travelling in a wagon which was being chased by wolves. When the man reached the safety of a city, he found the gates closed and while he shouted for help, the wolves overtook him and tore him to pieces. How do you feel about that tale, Ralan?’

Bek laughed. ‘I’d say that it is a pretty funny story! I wager he had a really amazing look on his face when those beasts caught up with him!’

Nakor was silent, then he stood. ‘You wait here. I’ll be back shortly.’ The Isalani walked straight to Pug’s study. He knocked, then opened the door before Pug told him to enter.

‘I need to speak with you, now,’ Nakor said.

Pug looked up from where he sat before an open window, enjoying the summer’s breeze. Magnus sat opposite him and both men studied the excited looking Isalani. ‘What is it?’ Pug asked.

‘That man, Ralan Bek, he is important.’

‘So you have said,’ Magnus replied.

‘No, even more important than we suspected. He understands the Dasati.’

Pug and Magnus exchanged startled expressions before Magnus asked, ‘Didn’t we agree not to speak of them to anyone outside our group?’

Nakor shook his head. ‘I’ve told him nothing. He knows them because he is like them. I now understand how they came to be the way they are.’

Pug sat back and said, ‘This sounds fascinating.’

Nakor said, ‘I don’t mean I understand every detail or even exactly how it is so, but I know what has happened.’

Pug motioned for Nakor to sit and continue.

‘When Kaspar described what Kalkin had shown him of the Dasati world, we all had the same reaction. After our concern over the threat they pose, we asked ourselves how such a race came to be. How could a people rise, grow and prosper without compassion, generosity and some sense of common interest?

‘I suspect they had them once, but evil became ascendant in that world, and this man is an example of what we will all become if the same evil gains pre-eminence here.’ Nakor paused, then stood and began to pace as if struggling to form his thoughts.

‘Bek is as the gods have made him.’ He looked at the young man, who nodded. ‘That is what he said to me, and he is correct. And he knows that he is not as the gods made other men. But he doesn’t yet begin to understand what that means.’

Nakor glanced around and continued, ‘No one in this room was made as other men are made. Each of us has been touched in one fashion or another, and because of that we are condemned to lead lives that are both uniquely wonderful and terrible.’ He grinned. ‘Sometimes both at the same time.’

His face resumed a thoughtful expression. ‘During our struggles with the agents of evil, we have pondered what purpose such evil serves, many times, and the best answer we have reached is an abstract hypothesis: that without evil, there could be no good, and that our ultimate goal, for the greater benefit of all, is to achieve a balance where the evil is offset by good, thus leaving the universe in harmony.

‘But what if the harmony we seek is an illusion? What if the natural state is actually a flux, the constant struggle? Sometimes evil will predominate, and at other times good. We are caught up in the endless ebb and flow of tides that wash back and forth over our world?’

‘You paint an even bleaker picture than usual, Nakor,’ Pug interrupted.

Magnus agreed. ‘Your ant-seige on the castle sounds more promising than being swept away on endless tides.’

Nakor shook his head. ‘No, don’t you see? This shows that sometimes the balance is destroyed! Sometimes the tide sweeps away all before it.’ He pointed to Bek. ‘He is touched by something that he doesn’t understand, but his understanding is not necessary for that thing to work its will upon him! The Dasati are not evil because they wanted to be that way. In ages past, I’d wager that they were not unlike us. Yes, their world is alien and they live on a plane of existence that would be impossible for us to endure, but Dasati mothers loved their children once, and husbands loved their wives, and friendship and loyalty flourished ages ago. The thing we call the Nameless One is but a manifestation of something far greater, a thing not limited to this world, this universe, or even this reality. It spans—’ he was lost for words. ‘Evil is everywhere, Pug.’ Then he grinned. ‘But that means, so is good.’

Nakor struck his left palm with his right fist. ‘We delude ourselves that we understand the scope of our decisions, but when we speak of ages, we do not understand them. The thing we fight has been preparing for this conflict since men were little more than beasts, and it is winning. The Dasati became what they are because evil won on their world, Pug. In that universe, what we call the Nameless One overturned the balance and it won. They are what we will become if we fail.’

Pug sat back, his face drawn and pale. ‘You paint a grim picture, my friend.’

Nakor shook his head. ‘No, don’t you see? All is not lost – if evil can win there—’ He looked at Pug, then at Magnus and his grin returned ‘—then good can win here!’

Later, Pug and Nakor walked along the sea shore, letting the warm breeze and salt spray invigorate them. ‘Do you remember Fantus?’ Pug asked.

‘Kulgan’s pet firedrake that used to hang around the kitchen from time to time?’

‘I miss him,’ said Pug. ‘It’s been five years since I last saw him, and he was very old, dying I think. He wasn’t really a pet, more of a house-guest.’ Pug looked out at the endlessly churning surf, the waves building up and rolling in to break upon the beach. ‘He was with Kulgan the night I first came to his hut in the woods near Crydee Castle. He was always around back then.

‘When I brought my son William from Kelewan, he and Fantus became thick as thieves. When William died, Fantus visited us less and less.’

‘Drakes are reputed to be very intelligent, perhaps he grieved?’

‘No doubt,’ said Pug.

‘Why think of him now?’ asked Nakor.

Pug stopped and sat on a large rock nestled into the cliff face where the beach curved into an outcropping. To continue their walk, they would have had to wade through the shallows around a headland. ‘I don’t know. He was charming, in a roguish sort of way. He reminded me of simpler times.’

Nakor laughed. ‘During our years of friendship, Pug, I’ve heard you talk of your simpler times but I would hardly count the Riftwar, your imprisonment in Kelewan, becoming the first barbarian Great One and then ending the war,’ he laughed, ‘and the Great Uprising, and all those other things you, Tomas and Macros accomplished as being anything close to simple!’

‘Maybe I was just a simpler man,’ said Pug, fatigue evident in his voice.