По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

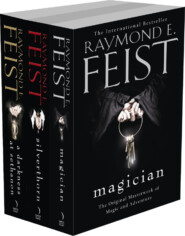

The Complete Riftwar Saga Trilogy: Magician, Silverthorn, A Darkness at Sethanon

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Then tell me, why has a wall grown between us?’

Roland sighed, and there was none of his usual roguish humor in his answer. ‘If there has, Carline, it is not of my fashioning.’

A spark of the girl’s former self sprang into being, and with a temperamental edge to her voice she said, ‘Am I, then, the architect of this estrangement?’

Anger erupted in Roland’s voice. ‘Aye, Carline!’ He ran his hand through his wavy brown hair and said, ‘Do you remember the day I fought with Pug? The very day before he left.’

At the mention of Pug’s name she tensed. Stiffly she said, ‘Yes, I remember.’

‘Well, it was a silly thing, a boys’ thing, that fight. I told him should he ever cause you any hurt, I’d thrash him. Did he tell you that?’

Moisture came unbidden to her eyes. Softly she said, ‘No, he never mentioned it.’

Roland looked at the beautiful face he had loved for years and said, ‘At least then I knew my rival.’ He lowered his voice, the anger slipping away. ‘I like to think then, near the end, he and I were fast friends. Still, I vowed I’d never stop my attempts to change your heart.’

Shivering, Carline drew her cloak about her, though the day was not that cool. She felt conflicting emotions within, confusing emotions. Trembling, she said, ‘Why did you stop, Roland?’

Sudden harsh anger burst within Roland. For the first time he lost his mask of wit and manners before the Princess. ‘Because I can’t contend with a memory, Carline.’ Her eyes opened wide, and tears welled up and ran down her cheeks. ‘Another man of flesh I can face, but this shade from the past I cannot grapple with.’ Hot anger exploded into words. ‘He’s dead, Carline. I wish it were not so; he was my friend and I miss him, but I’ve let him go. Pug is dead. Until you grant that this is true, you are living with a false hope.’

She put her hand to her mouth, palm outward, her eyes regarding him in wordless denial. Abruptly she turned and fled down the stairs.

Alone, Roland leaned his elbows on the cold stones of the tower wall. Holding his head in his hands, he said, ‘Oh, what a fool I have become!’

‘Patrol!’ shouted the guard from the wall of the castle. Arutha and Roland turned from where they watched soldiers giving instructions to levies from the outlying villages.

They reached the gate, and the patrol came riding slowly in, a dozen dirty, weary riders, with Martin Longbow and two other trackers walking beside. Arutha greeted the Huntmaster and then said, ‘What have you there?’

He indicated the three men in short grey robes who stood between the line of horsemen. ‘Prisoners, Highness,’ answered the hunter, leaning on his bow.

Arutha dismissed the tired riders as other guards came to take position around the prisoners. Arutha walked to where they waited, and when he came within touching distance, all three fell to their knees, putting their foreheads to the dirt.

Arutha raised his eyebrows in surprise at the display. ‘I have never seen such as these.’

Longbow nodded in agreement. ‘They wear no armor, and they didn’t give fight or run when we found them in the woods. They did as you see now, only then they babbled like fishwives.’

Arutha said to Roland, ‘Fetch Father Tully. He may be able to make something of their tongue.’ Roland hurried off to find the priest. Longbow dismissed his two trackers, who headed for the kitchen. A guard was dispatched to find Swordmaster Fannon and inform him of the captives.

A few minutes later Roland returned with Father Tully. The old priest of Astalon was dressed in a deep blue, nearly black, robe, and upon catching a glimpse of him, the three prisoners set up a babble of whispers. When Tully glanced in their direction, they fell completely silent. Arutha looked at Longbow in surprise.

Tully said, ‘What have we here?’

‘Prisoners,’ said Arutha. ‘As you are the only man here to have had some dealings with their language, I thought you might get something out of them.’

‘I remember little from my mind contact with the Tsurani Xomich, but I can try.’ The priest spoke a few halting words, which resulted in a confusion as all three prisoners spoke at once. The centermost snapped at his companions, who fell silent. He was short, as were the others, but powerfully built. His hair was brown, and his skin swarthy, but his eyes were a startling green. He spoke slowly to Tully, his manner somehow less deferential than his companions’.

Tully shook his head. ‘I can’t be certain, but I think he wishes to know if I am a Great One of this world.’

‘Great One?’ asked Arutha.

‘The dying soldier was in awe of the man aboard ship he called ‘Great One.’ I think it was a title rather than a specific individual. Perhaps Kulgan was correct in his suspicion these people hold their magicians or priests in awe.’

‘Who are these men?’ asked the Prince.

Tully spoke to them again in halting words. The man in the center spoke slowly, but after a moment Tully cut him off with a wave of his hand. To Arutha he said, ‘These are slaves.’

‘Slaves?’ Until now there had been no contact with any Tsurani except warriors. It was something of a revelation to find they practiced slavery. While not unknown in the Kingdom, slavery was not widespread and was limited to convicted felons. Along the Far Coast, it was nearly nonexistent. Arutha found the idea strange and repugnant. Men might be born to low station, but even the lowliest serf had rights the nobility were obligated to respect and protect. Slaves were property. With a sudden disgust, Arutha said, ‘Tell them to get up, for mercy’s sake.’

Tully spoke and the men slowly rose, the two on the flanks looking about like frightened children. The other stood calmly, eyes only slightly downcast. Again Tully questioned the man, finding his understanding of their language returning.

The centermost man spoke at length, and when he was done Tully said, ‘They were assigned to work in the enclaves near the river. They say their camp was overrun by the forest people – he refers to the elves, I think – and the short ones.’

‘Dwarves, no doubt,’ added Longbow with a grin.

Tully threw him a withering look. The rangy forester simply continued to smile. Martin was one of the few young men of the castle never intimidated by the old cleric, even before becoming one of the Duke’s staff.

‘As I was saying,’ continued the priest, ‘the elves and dwarves overran their camp. They fled, fearing they would be killed. They wandered in the woods for days until the patrol picked them up this morning.’

Arutha said, ‘This fellow in the center seems a bit different from the others. Ask why this is so.’

Tully spoke slowly to the man, who answered with little inflection in his tones. When he was done, Tully spoke with some surprise. ‘He says his name is Tchakachakalla. He was once a Tsurani officer!’

Arutha said, ‘This may prove most fortunate. If he’ll cooperate, we may finally learn some things about the enemy.’

Swordmaster Fannon appeared from the keep and hurried to where Arutha was questioning the prisoners. The commander of the Crydee garrison said, ‘What have you here?’

Arutha explained as much as he knew about the prisoners, and when he was finished, Fannon said, ‘Good, continue with the questioning.’

Arutha said to Tully, ‘Ask him how he came to be a slave.’

Without sign of embarrassment, Tchakachakalla told his story. When he was done, Tully stood shaking his head. ‘He was a Strike Leader. It may take some time to puzzle out what his rank was equivalent to in our armies, but I gather he was at least a Knight-Lieutenant. He says his men broke in one of the early battles and his “house” lost much honor. He wasn’t given permission to take his own life by someone he calls the Warchief. Instead he was made a slave to expiate the shame of his command.’

Roland whistled low. ‘His men fled and he was held responsible.’

Longbow said, ‘There’s been more than one earl who’s bollixed a command and found himself ordered by his Duke to serve with one of the Border Barons along the Northern Marches.’

Tully shot Martin and Roland a black look. ‘If you are finished?’ He addressed Arutha and Fannon: ‘From what he said, it is clear he was stripped of everything. He may prove of use to us.’

Fannon said, ‘This may be some trick. I don’t like his looks.’

The man’s head came up, and he fixed Fannon with a narrow gaze. Martin’s mouth fell open. ‘By Kilian! I think he understands what you said.’

Fannon stood directly before Tchakachakalla. ‘Do you understand me?’

‘Little, master.’ His accent was thick, and he spoke with a slow singsong tone alien to the King’s Tongue. ‘Many Kingdom slaves on Kelewan. Know little King’s Tongue.’

Fannon said, ‘Why didn’t you speak before?’

Again without any show of emotion, he answered, ‘Not ordered. Slave obey. Not . . .’ He turned to Tully and spoke a few words.