По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

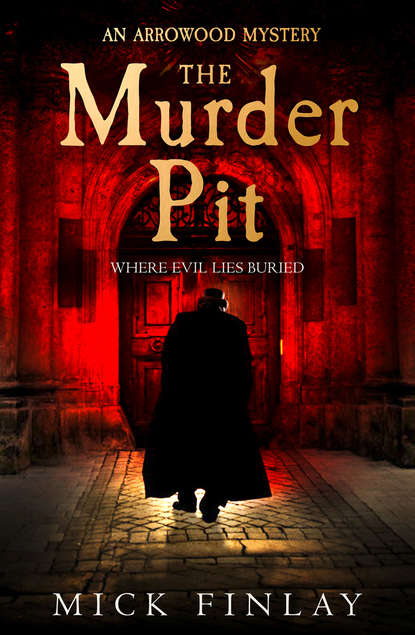

The Murder Pit

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Reckon he’s a man, sir,’ I replied. ‘Twenty-five year at least.’

‘Well, I like him.’ He sighed, patted his belly, and looked around the camp. It was only then I spotted the crows, three of them, standing by a bush on the other side of the stream. They were pecking away at something hidden in the leaves. A bad feeling came over me. As I approached, the birds hopped away, watching me with their dead, black eyes. One had a string of flesh hanging out of its mouth. It was only when I stepped over the fallen tree I saw what they’d been picking at: it was Mrs Gillie’s cat, its innards pulled and scraped from its shell.

‘Look, William,’ I said, pointing.

Its skull was beaten to a pulp.

Chapter Eleven (#ulink_0ed10ae3-eca5-5a1f-ab72-42aa45f6dcc7)

The same young fellow was behind the desk of the police station when we arrived. He went into the back room to fetch Sergeant Root, who listened to the guvnor’s story with a frown, his dirty fingers tap-tapping on the desk.

‘She’s joined another camp,’ he said when the guvnor finished, his eyelids drooping like he was bored. ‘They don’t stay in one place long.’

‘She’s left her horse, her coat, her boots,’ answered the guvnor. ‘Her caravan door was wide open, Sergeant.’

‘They’re easy like that. I appreciate you letting us know, sir.’

Root turned back to the room.

‘Sergeant!’ said the guvnor sharply. ‘You must at least go down and have a look. She’s an old woman, for pity’s sake!’

‘Tinkers disappear, that’s what they do. And usually after they’ve emptied a house of its silverware. You know they’ve been thieving from the building sites, I suppose?’

‘There’s been trouble, I tell you,’ said the guvnor. ‘The flowers she sells are scattered on the ground. And how d’you explain the cat? No animal could have done that.’

‘Killing a cat ain’t a crime, Arrowood, just as not wanting to see your parents ain’t neither.’

The young copper nodded at this. His neck was pale and long out of his frayed uniform jacket. Root pulled out his watch.

‘Half one, Thomas,’ he said to the lad. ‘I’m off for dinner. You hold the fort.’

He took a thick, black overcoat from the peg and wrapped himself in it.

‘Please, Sergeant,’ said the guvnor. Though he seemed to be asking a favour, his voice had a hard edge to it. ‘Have a look. That’s all we ask.’

The copper buttoned his coat, then pulled his gloves from his pocket. He took his helmet from another hook and jammed it on his head. Finally, he replied:

‘Mr Arrowood. I’m grateful you bringing this to me, but it’s honest folk as pay our wages, not the likes of them. If she’s had trouble it’s from her own kind. They don’t want to be like the rest of us. Don’t want to be in with us.’ He opened the door and stepped out. ‘Her and her lot been staying round here when it suits them ever since I can remember. They’ve their own justice. Don’t appreciate the police poking around their affairs.’

‘She might be in danger!’ exclaimed the guvnor, making a grab for his arm.

‘Get off me!’ barked the copper, his face and neck come over quite red. He prised the guvnor’s fingers from his arm, stepped out into the cold street, and banged shut the door.

‘Damn!’ cursed the guvnor. He looked at the lad. ‘I don’t suppose you’d come and have a look, son?’

‘Wouldn’t know what to look for, sir,’ said the boy. ‘I only started here last week. Just been stood here, really.’

*

We had a sandwich in the pub, then called on Sprice-Hogg. The parson was on his way out. His overcoat was missing two buttons; his curly white hair fell from his broad-brimmed hat.

‘We enjoyed ourselves the other night, didn’t we, gentlemen?’ he asked, his smile like a basket of chips.

‘That we did, Bill,’ replied the guvnor.

‘I visited Birdie yesterday. She really does want nothing to do with her parents. It seems they wanted rid of the poor girl.’

‘And she told you that, did she?’

‘Rosanna told me, but Birdie was there. She wanted Rosanna and Walter with her. She lacks confidence in her speaking.’

‘Did Birdie tell you she wanted them with her, Bill?’

‘Well, it was Walter went to fetch her. I believe she asked him.’

The guvnor frowned for a very brief moment. ‘But we don’t know if she really did want them there?’

‘Ah, I see. You think like a detective. I’m afraid I don’t, but I can’t imagine they prevented her seeing me alone. I’ve known them for years. They wouldn’t do that.’

‘Thank you, Bill,’ said the guvnor with a sigh. ‘Listen, we wanted to catch Godwin away from the farm. D’you know if he goes to the pub very often?’

‘He’ll be there tonight, I’m sure. A bit too fond of a drink, that man.’

Sprice-Hogg had an appointment, but he suggested we wait in the parsonage until evening, and soon we were sat in his parlour warming our feet by the coals. Sarah brought us tea and the papers, and we spent a few hours in comfort.

‘Idiots!’ declared the guvnor, waking me from a doze.

‘Sir?’ I asked, my mind fugged from sleep. He was reading the Illustrated Police News.

‘A whole page on the damn Swaffham Prior case. They’ve found another fool to blame. Some bombazine. Good Christ, the paper’s all but tried and convicted him. And there were more speeches in Parliament defending the boys.’

He turned the page furiously.

‘Another article on criminal anthropology,’ he murmured. He studied it for a few moments. ‘D’you believe Lombroso’s scheme? That you can identify a criminal from his face?’

‘Maybe. I don’t know.’

‘They’ve some pictures here.’ He studied the paper, then peered at me through his eyeglasses. Then he examined the paper again. ‘Well, look at you,’ he said at last. ‘Oh dear, dear, Barnett. I believe you’re one of these types. Bulging forehead; long lobes; eyes far apart. Dear, dear. It appears you’re a degenerate, my friend.’

‘I haven’t got a bulging forehead.’

‘It bulges, Barnett. Don’t be vexed with me for saying it.’

‘My eyes are no more apart than yours.’

He concentrated on lighting his pipe, but I could see he was trying to stop himself grinning. When it had a blaze, he said, ‘I didn’t say I agree with Lombroso. You just match one of his types.’

I said nothing. Truth was I sometimes suspected I was a degenerate. He didn’t know some of the things I’d done back when I lived with my ma in one of the worst courts in Bermondsey. Down there you had to be a degenerate to get by, and I’d done a few things I wasn’t proud of, things he’d never had to do coming from the background he did. It started when I was eleven, the very week we moved out of the spike to that dismal room with the wet floor in the most run-down building in the court. We could only get the room on account of me getting a job in the vinegar factory, but that very first Saturday three older lads jumped me on my way home and nicked my wages. The same happened the next Saturday, and the Saturday after, and soon ma and me were four weeks behind on the rent and run out of tick in the shop. That’s how I went out late one night, when my ma was asleep, looking for them. I didn’t know what I’d do until I found the youngest passed out from gin by the outhouse. Then I knew: I went back to the room where there was a can of paraffin, almost empty. A box of matches. I set him alight and watched him burn until he woke, screaming and twisting. That was the start of it all, of all the things I’ve tried to forget.

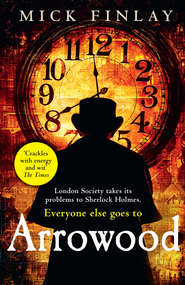

Другие электронные книги автора Mick Finlay

Arrowood

0

0