По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

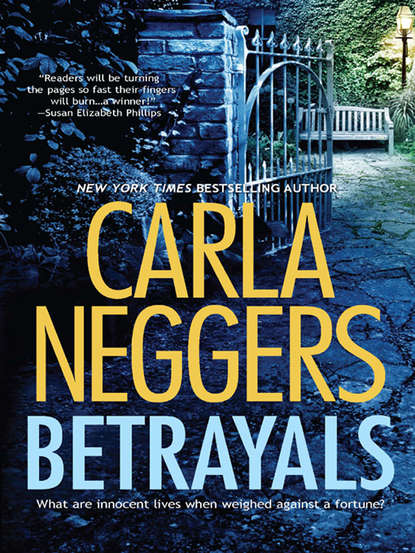

Betrayals

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

One

The French Riviera

1959

Annette Winston Reed hacked at an onion on the battered worktable in her airy, sun-washed kitchen. Although it wasn’t her nature to fret, she noticed her hands were shaking and she was perspiring heavily. Her underarms and the small of her back were damp, and her eyes burned with lack of sleep. It’s time to buck up, she silently told herself, annoyed by this betrayal of her inner turmoil. She wasn’t going to let her troubles undermine her self-confidence or her sense of fun.

She refused to let Thomas Blackburn get to her. He and his four-year-old granddaughter had come down for the weekend from Paris, a typical presumptuousness on Thomas’s part. Annette hadn’t invited him. A Bostonian like herself, he had known her all her life. She had grown up around the corner from his house on Beacon Hill. But as much as she looked up to him, as much as she’d wanted him to admire her, she couldn’t consider him a friend. He was too old, almost twenty years her senior, and perhaps knew her too well. With Thomas, pretenses were impossible.

He was at the breakfast table overlooking the rose garden, with a mug of black coffee at his elbow and the Paris Le Monde opened up in front of him so that Annette couldn’t miss the latest blaring headline about the jewel thief who’d plagued the Côte d’ Azur for the past eight weeks. He’d been dubbed Le Chat after the Cary Grant character in the popular American movie To Catch a Thief. Once again, the police promised the imminent arrest of a suspect.

This time they weren’t just blowing smoke. Annette knew better.

Thomas hadn’t said a word beyond a simple good-morning. He had come to the Riviera just to visit her, he’d told Annette with his wry smile, knowing she wouldn’t believe him. As always, he had a loftier purpose in mind: to convince her Vietnamese caretaker, a mandarin scholar respected both abroad and in his own country, to return home. Thomas would go on and on about how Saigon needed credible centrist leaders and how Quang Tai could help save his country from disaster, and Annette would pretend a suitable neutrality, despite the prospect of losing her caretaker. She was only sparing herself one of Thomas’s notorious lectures on not being shortsighted and selfish; she suspected he already knew she didn’t want the bother of having to replace Quang Tai.

She sighed, frantically mincing one half of the onion. Her eyes had begun to tear, and if she didn’t slow down and be careful, she’d likely chop off the end of a finger. Thomas wouldn’t keep quiet for long. It wasn’t a Blackburn trait.

The newspaper rustled as he turned a page, and she heard him take a small sip of coffee.

“All right, Thomas, you win,” she said, whirling around with her paring knife. “What do you want to tell me that you’re trying so hard not to tell me? You might as well spit it out, because you know you’ll get around to it sooner or later.”

Looking slightly miffed at her sharp-sighted observation, Thomas folded the newspaper and laid it on the table. Like all Blackburns, he was a man of impeccable moral and intellectual respectability—the kind of highbrow Bostonian that Annette usually found boring and irritating. For two centuries, the Blackburns had been outspoken patriots, historians, poets, reformers, public servants and eccentrics, if not the best moneymakers. Eliza Blackburn—the patron saint of the family—was one of Boston’s favorite Revolutionary War heroines. Her portrait, painted by Gilbert Stuart, hung in the Massachusetts State House; in it she wore the cameo brooch that George Washington himself had presented to her, in gratitude for her efforts at smuggling weapons, ammunition and information from British-occupied Boston to the patriot forces in outlying areas. The Winstons, on the other hand, had snuck off to Halifax for the duration of the War of Independence. Eliza had also been virtually the only mercantile-minded Blackburn in two hundred years. She’d been the driving force behind Blackburn Shipping, which made a fortune in the post-Revolution China trade, but folded in 1812 with the British blockade and the war. That was that for a Blackburn generating any substantial income. Eliza’s descendants had been stretching her fortune ever since, and it was beginning to fray.

Annette had heard rumblings that Thomas, Harvard-educated and approaching fifty, was about to launch his own business. He was an authority on the history and culture of Indochina and spent much of his time there, but how he planned to translate that expertise into a moneymaking enterprise was beyond her.

He regarded her with a calm that only accentuated her own nervousness. “Annette, I’d like to ask you a straightforward question—do you know this thief Le Chat?”

“Don’t be ridiculous. How would I know him?”

Her mouth went dry, her heartbeat quickened and she felt curiously light-headed. She’d never fainted in all her thirty years; now wasn’t the time to start. Trying to hide her trembling hands, she set down the paring knife and leaned against the counter. She was dressed casually in baggy men’s khaki trousers and an oversize white cotton shirt, her ash-brown hair pulled up in a hasty knot. If she worked at it, she could look rather stunning at first glance, but she had no illusions that she was an especially beautiful woman. She was too pale-skinned, too large-framed, too pear-shaped, too tall. Her near-black eyebrows were mannishly heavy and might have overwhelmed a more delicate face, but she had a strong nose, Katharine Hepburn cheeks and big eyes that were a ringing, memorable blue—her best feature by far. She’d hated her long legs as a teenager, but over the years she had discovered they had their advantages in bed. Even her husband, not the most passionate of men, would cry out in pleasure when she’d wrap them around him and pull him deeper into her.

“Annette,” Thomas said.

It was the same tone he’d used on her when he’d caught her crossing Beacon Street alone at six years old. Nineteen years her senior, he was already a widower then, with a two-year-old son. Emily Blackburn, so quietly beautiful and intelligent, had died of postpartum complications, the first person Annette had ever known to die. She had only wanted to ride the swan boats in the Public Garden and had explained this to Thomas, assuring him her mother had said it was all right. He had said, “Annette,” just that way—admonishing, knowing, expecting more of her than a transparent lie. Feeling as if she’d failed him, she’d blurted out the truth. Her mother hadn’t said it was all right; she thought Annette was playing alone in the garden. Thomas had marched her home at once.

She was no longer six years old.

“I promised the children I’d take them out to pick flowers,” she said, pulling herself up straight. “They’re waiting.”

She was at the kitchen door when Thomas spoke again. “Annette, this man’s no Cary Grant. He’s a thief who has lined his own pockets with other people’s things and driven a decent woman to suicide.”

Annette spun around and gave him a haughty look. “I quite agree.”

Shaking his head, Thomas rose to his feet. He was a tall, lean man with sharp features and straight, fine hair that was a mixture of dark brown, henna highlights and touches of gray. The scrimpiest of the notoriously frugal Blackburns, he wore a shabby sweater that had probably seen him through his postgraduate studies at Harvard and trousers he’d let out, unabashedly leaving the old seam to show.

“I would never presume to judge you,” he told her softly. “I hope you know that.”

Annette held back an incredulous laugh. “Thomas, you’re a Blackburn. It’s your nature to judge everyone and everything.”

He grimaced, but there was a gleam in his intensely blue eyes. “You’re saying I’m a critical old fart.”