По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

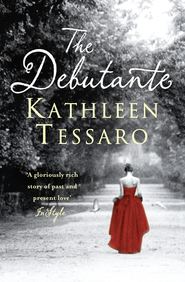

Elegance and Innocence: 2-Book Collection

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

And then, well into my third week of unbridled wretchedness, the jumper goes missing.

One morning it’s where I left it in a loving, crumpled heap on the corner of my bed and by that afternoon, it’s gone. I search frantically throughout the whole of my tiny room, flinging the contents out of my half unpacked bags and tearing the sheets off my bed. Then I expand my hunt to the living room and its environs, overturning sofa cushions and rifling through the laundry basket. It isn’t until I’ve exhausted every possibility and am bordering on hysteria that it occurs to me; I’m not dealing with a simple case of a misplaced jumper, I’m dealing with a kidnapping.

Suspiciously, both of my new flatmates have retired early for the night. I knock on Colin’s door first.

‘It wasn’t me!’ he shouts over his new Robbie Williams CD.

‘But you know about it, you traitor!’ I rage, stamping down the hall to pound on Ria’s door.

‘Ria, I believe you have something that belongs to me and I want it back!’

A tiny, sullen voice answers firmly. ‘No.’

I’m flabbergasted. ‘What do you mean “No”! That’s my jumper! You have to return it!’

‘No. It’s bad for house morale.’

Now I’m stunned. ‘You cheeky, little fart! How can it be bad for house morale? It’s got nothing to do with house morale!’ I rattle the doorknob threateningly.

She opens the door a crack. Five feet tall in her stockinged feet, Ria peers at me like a mischievous elf. ‘It has everything to do with house morale when one person has completely given up even trying to pull themselves together.’

Colin’s head pops out from behind his door too. ‘She has a point, Ouise.’

It’s more than I can bear. My eyes sting and my throat’s so tight, I can hardly breathe. ‘I don’t want to discuss it. Just give it back to me. I’m not in the mood for jokes.’

Ria takes my hand. ‘But, darling, believe me, this … this … over-indulgence is not the way to mend a broken heart. You’re doing yourself more harm than good.’

I pull my hand away. ‘What does it matter what I do, as long as I’m quiet and pay my rent? What difference could it possibly make to you! Why should you care, anyway?’

‘Louise …’ She’s taken aback but I can’t help myself.

‘Don’t! Don’t even pretend you care about what happens to me! Do you realize … have you even noticed that my own husband hasn’t rung once since I arrived? Do you know what that means? Do you have any idea?’

‘Honey, I’m sorry …’

‘He doesn’t want me back!’ I point out to her, tears rolling down my face. ‘He doesn’t even want the fucking jumper back!’

I run into my room and slam the door. I’m acting like a child, throwing a temper tantrum. Shocked as I am at the violence of my reaction, any shred of self control has disappeared. I curl up on the bed, sobbing pathetically into my pillow, beating my fists into the mattress. I’m as powerless and impotent as a child.

Suddenly, I’m seized by an overwhelming sense of déjà vu. And memory from long ago.

This isn’t the first time I’ve stolen a jumper.

The first one was my father’s; an ancient moss green pullover of his which hung in the laundry room by the garage. He wore it to do chores in but in its heyday, it had been to countless fraternity parties and dates during his college years. It was his constant companion during the long nights of studying for law school and the more it deteriorated, the more he loved it. When my mother finally exiled it from his daily wardrobe, it lingered on, waiting patiently for him, like a once fine show dog grown old in all its shabby, soft splendour.

The most enduring image I have of my father, is of distraction. His mind was always elsewhere. A whirlwind of activity, he could lose weight just getting dressed in the morning. ‘I have a list of things to do today,’ was his constant refrain. ‘A list of things to do.’ And he’d be off. He’d set himself heroic, impossible tasks to accomplish. ‘I’ll rewire the house by dinner time.’ (My father was not an electrician.) Or ‘I’m sure there’s a way of building an indoor pool by yourself.’ And then he’d disappear. There was always one more job that had to be done, some final thing that needed urgent attention, one more essential bit of home improvement that absolutely must be completed by dusk. With only his faithful green jumper to keep him warm, he’d vanish into the sunset, never to be seen again, lost in a blur of perpetual motion.

It wasn’t easy to get my father’s attention, but you could steal his jumper if you were desperate.

Trouble is, we were all desperate and the competition for that jumper was fierce.

Traditionally, my mother had first dibs. But she had other, more effective ammunition in her armoury. She had perfected a fail-proof technique to grab my father’s attention that the rest of us could only marvel at. Since my father loved to fix things, she’d deduced that the best way to secure his attention was to be broken. Accordingly, she suffered from strange, debilitating headaches that could strike without a moment’s warning and last anywhere from twenty minutes to two weeks, as required. It was genius. If he was going to be distracted, he could be distracted with her. As a consequence, she pretty much had a copyright on any form of illness in our family. Occasionally my brother or sister would do a weak imitation, a kind of tribute to the master, but it’s hard to compete with someone who isn’t afraid to pass out.

Effective as it was, it had its downside. By the year I turned seventeen, my mother had got fed up with the invalid routine. It must have dawned on her that she was worth more and that made her angry. So angry that she stopped talking to my father altogether. It was known as the Year of Silence.

It was a dismal time aggravated by their refusal to admit it was happening.

‘Mom, why are you and Dad not talking?’

‘We are talking. We just don’t have anything to say.’

His voice was on a frequency she no longer registered. Anger hung over the household like a thunderstorm that refused to break, the pressure building day by day. My father still fixed things, probably even more so now that he didn’t have all the diversions of conversation, but my mother greeted each accomplishment with Sphinx-like indifference. We were all horrified to see how easy it was to vanish from her affections. The invisible man had finally disappeared altogether.

During this time, my dad and I became friends. We drove into school together in the mornings and there, in the sanctuary of the car, he listened to my endless Bowie compilation tapes and quizzed me about my studies. When I read Dickens, he bought a volume and read it too. And that’s when I started to wear the moss green jumper by the door.

One day I came home from school with it on and my mother saw me.

‘Don’t wear that again,’ she warned. She had a way of saying things.

I tossed my hair out of my heavily lined eyes. ‘Why not?’ I challenged.

My mother said nothing. Her silence could spill out in all directions.

‘What difference does it make to you, Mom,’ I persisted. ‘It’s not like you wear it any more.’

She gave me a look. ‘Just don’t.’

The next day I wore it again.

This went on for some weeks. My mother warned me. I ignored her. My father was nowhere to be seen.

And then, on my seventeenth birthday, I came home from school with my father and my best friend. My mother was standing in the kitchen with a birthday cake she’d picked up on her way home from work and as I walked in, her face fell. There I was holding my father’s hand, laughing, and wearing the jumper. She brushed past my father, grabbed my arm, her fingernails digging into my flesh, and dragged me into the hall.

‘That doesn’t belong to you!’ she hissed, barely able to control the venom in her voice. ‘Do you understand me? That doesn’t belong to you!’ She stared at me, a strange, fierce stare. At last she let go of my arm.

I didn’t wear the jumper after that. It went back on its hook in the laundry room and hung there uneventfully for several months.

Then one spring afternoon, I noticed my mother wearing it while she and my dad washed the car. My father was Hoovering the interior, all his attention on the task in hand, and my mother was emptying out a pail of dirty, black water. To anyone else they looked like a normal couple engaging in a traditional Sunday afternoon chore. But I saw a different picture.

My mother had given up. The Year of Silence had failed. My father probably didn’t even notice she’d nicked the jumper, he was so intent on completing his list of things to do. But she was back to stealing what she could from him; moments of companionship and the intimacy of the jumper.

She was right; it didn’t belong to me. Things you have to steal never do.

Now the sun is setting outside. I sit up on my bed and blow my nose. When I open my bedroom door there, neatly folded on the floor, is the navy blue jumper.

Stepping over it, I walk into the living room where Colin and Ria are watching a late night chat show about royal impersonators. Colin mutes the sound and they both look up at me.

‘I’m sorry,’ I begin. ‘You were right about the … the jumper thing … it isn’t helping.’ I’m staring at my shoes. I’ve never had to apologize as an adult for having a temper tantrum before. It’s much harder and more humbling than I thought. ‘The truth is, I’m not very good at being on my own …’ Even as I say it, this seems like the understatement of the year. ‘I don’t really know how to … you know, do it.’