По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

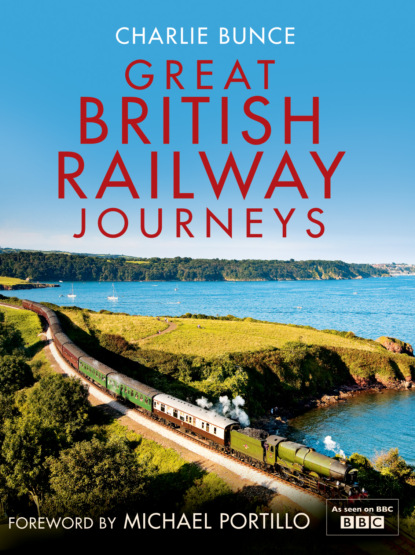

Great British Railway Journeys

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Camilla had long been obsessed with finding a new way of investigating our social history. Her brother-in-law, an antiquarian bookseller slotted the last piece of the puzzle in place when he told her that George Bradshaw, the man who famously started producing monthly railway timetables in the mid-nineteenth century had also published a guide-book on travelling across the country by train.

After a £500 investment, a battered and broken copy of Bradshaw’s guide arrived at the office. A drab brown cover was misleading as its contents were anything but dull and dreary. Its well-thumbed pages offered a remarkable insight into the life and times of Victorian Britain.

The more I read Bradshaw’s guide, the more I could hear his voice. As I understood him better I began to see the age in which he lived and worked, and to see what excited him and why. His minute observations and comments gave me a sense of Victorian Britain different from anything I’d read before.

His rich words conveyed to us another age. A section about Sandwich in Kent is an ideal example. ‘The traveller, on entering this place, beholds himself in a sort of Kentish Herculaneum, a town of the martial dead. He gazes around him and looks upon the streets and edifices of a bygone age. He stares up at the beetling stories of the old pent-up buildings as he walks and peers curiously through latticed windows into the vast low-roofed, heavy-beamed, oak-panelled rooms of days he has read of in old plays.’

How could you not want to visit Sandwich and find what he had seen. Beyond lyrical descriptions, Bradshaw deposited on his pages a wealth of information about where his readers should stay, how to get money, what day the market took place, local sights of interest and on occasion where to sit to get the best view from the train. He revelled in detail, giving the span and height of bridges to the foot, or the length of station platforms. He loudly and proudly celebrated every British success.

George Bradshaw combined his enthusiasm for cartography with a passion for trains.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

Bradshaw described how the railways were a great leveller, literally and metaphorically. While the land was planed so the trains could run on as few inclines as possible, the barriers that divided a class-ridden society were at the same time pared down.

For the enterprising, railways represented a golden opportunity. Although they were initially seen as a way of transporting freight, it wasn’t long before moving people by rail was just as important, sometimes even more so. Commerce spread across neighbourhoods and regions. Trades that were once restricted to narrow localities could now take advantage of markets worldwide. The notion of commuting was born. Holidays, once the province of the rich, came within grasp of ordinary people.

It is difficult to imagine now just how fundamentally life changed and the speed at which those transformations came about. Where railway stations were made, hamlets mushroomed into towns while those settlements that were leapfrogged by railway lines were left in the doldrums.

Bradshaw was an expert artist, and his line drawings of some of the country’s finest buildings were included in his popular guidebooks.

It wasn’t all good news, though. Amid the euphoria that accompanied the age of steam there were many who fell victim to railway mania, including those who died laying tracks in hostile terrain and the unwary who invested heavily in lines or companies that failed to flourish.

As far as the programme was concerned, the idea was beguilingly simple. We would travel Britain by train with Bradshaw as our guide. Through it, we’d explore the impact of the railways on our cities, countryside and coast. Thanks to Bradshaw, we could celebrate triumphs of yesteryear and match fortunes past and present. We would see how the country had been transformed in a matter of a few short years and understand why, at the time, the British Empire was so successful at home and overseas. But, as importantly, we would search out what of Bradshaw’s Britain still remains today.

The next question was who should present it. In television, getting this agreed is often a monumental feat. On this occasion it wasn’t. Michael was suggested, and within 30 seconds of meeting him I knew he was the perfect candidate. The son of a Spanish refugee and a Scottish mother, Michael not only had a lifelong fascination for history but was also a former Minister of Transport. Years spent in both government and opposition did nothing to diminish his abiding passion for railway journeys. Forty-five episodes later I have never once regretted the decision to have him present the show. The energy and intelligence he brings to every situation make the series stand out.

London landmarks were also illustrated by Bradshaw for visitors to the capital.

Michael Portillo spoke with fellow railway enthusiasts up and down the country – here with Ian Gledhill, chairman of Volk’S Electric Railway Association.

© Steve Peskett

Strangely, the most taxing bit of the whole process was coming up with the right title. List after list was emailed to everyone concerned with the project, only to be knocked back, judged not quite right. We must have gone through hundreds of suggestions before ending up with Great British Railway Journeys. In the end, it seemed to say very succinctly what the series is all about.

The last question was where those journeys should take us. We could not mimic Bradshaw minutely on our travels. His extraordinary thoroughness meant that was a task too far, and many of the stations he visited are now obsolete, thanks to the policies of the Sixties which saw thousands of miles of branch lines closed in a futile bid to save cash.

Nonetheless, I wanted the trips we recorded to reveal a country that many of us hardly know, or at least seem to have forgotten. With our copy of Bradshaw’s guide in hand we’ve now made nine big journeys exploring the country and discovering new sides to places I thought I knew well. Through making the programmes and writing the book, I have had the chance to tease out dusty nuggets of information to satisfy the most curious of minds. I wanted the chance to trumpet what had been great about Britain, and celebrate the enormous amount that still is. I hope the series and this book do just that.

Charlie Bunce

September 2010

As he travelled through Britain Michael Portillo kept his well-worn copy of Bradshaw’s railway guide close at hand.

© Steve Peskett

JOURNEY 1

COTTONOPOLIS AND THE RAILWAYS

From Liverpool to Scarborough

The obvious place to start our journeys seemed to be the birthplace of the modern passenger railway. Lots of places lay claim to that title, but for us, once we’d looked into it, the Liverpool & Manchester Railway was the clear winner. It is true that fare-paying passengers had been carried by rail before its inception, but the Liverpool & Manchester was different. Unlike the other railways that predated this one, carriages were not horse-drawn, nor were they pulled along wires fixed to a stationary locomotive. It wasn’t a tiny pleasure railway with limited use. This was a proper twin-track line, the first in the world where steam locomotives hauled paying passengers, and it changed the face of travelling in Britain.

There are certainly longer, older and more beautiful routes, but the line between Liverpool and Manchester seemed to us to be the perfect launch pad into the past.

The original purpose of the line wasn’t to service passengers at all, but to move freight between two booming cities. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, most goods were transported on a thriving and extensive canal system, but it was both expensive and slow, and this trip took 36 hours. So in 1822 Joseph Sandars, a local corn merchant and something of a forward thinker, decided to invest £300 of his own money in surveying a route for a railway between Liverpool and Manchester.

The project suffered numerous setbacks as aristocratic local landowners campaigned to prevent the proposed line from passing through their lands, while the canal owners, fearful of competition, tried to stop it altogether. It looked for a while as though it would never get off the ground until another blow turned out to be the line’s saving grace. When the project’s original surveyor landed himself in jail, George Stephenson (1781–1858) was appointed in his place.

Stephenson was one of those great Victorians for whom nothing seemed impossible. Born to parents who could neither read nor write, he went on to become an inventor, a civil engineer and a mechanical engineer. He designed steam engines, bridges, tunnels and rail tracks. Whilst there’s disagreement over whether his skills lay in invention or in harnessing other people’s creations, he is rightly known as the father of the railway. Without a doubt, the modern railway developed more quickly than it would have done without Stephenson’s involvement.

On the line for the Liverpool & Manchester Railway, one of the first things Stephenson was tasked with was re-examining the route. What he came up with was a new plan which as much as possible skirted contested land. In this instance it wasn’t an easy option. It would require building no fewer than 64 bridges and viaducts along its 35-mile course and needed Parliamentary permission before it could begin.

Engineer George Stephenson is considered the father of the railways.

Maria Platt-Evans/Science Photo Library

It took four years of haggling before the Parliamentary Bill was passed in May 1826, enabling the compulsory purchase of land for the railway. Getting to this point had cost many compromises, however, one of which was that the line couldn’t go into Liverpool itself and instead had to halt outside the city centre. After the opening of the line in 1830 it was a further decade before it could be extended into the city and Lime Street station, one of Britain’s first railway stations, was opened.

In the middle of the nineteenth century Manchester was the centre of the cotton industry and Liverpool was a bustling dockyard. In fact, Bradshaw’s Descriptive Railway Hand-Book, the Victorian railway bible that we used throughout our travels around Britain, hails Manchester as ‘sending its goods to every corner of the world’. Liverpool had the port to facilitate doing just that. Bradshaw calls the docks ‘the grand lions of the town which extend in one magnificent range of five miles along the river from Toxteth Park to Kirkdale’. By 1850 – just 20 years after the Liverpool & Manchester line opened – Liverpool docks were the second most important port in Britain, handling 2 million tons of raw cotton every year destined for the Lancashire mills.

For Liverpool, it wasn’t all about freight. Moving people was also big business. Liverpool was one of the points on the notorious transatlantic slave trade triangle. Ships left the port with goods and headed for Africa, where the cargo was traded for slaves. The same ships then embarked on an often treacherous journey known as ‘the middle passage’ to America. Men, women and children who survived the crossing were consequently sold to work in plantations.

The slave trade – although not slavery itself – was finally abolished in Britain by an 1807 Act of Parliament, despite vociferous efforts by some Liverpool merchants keen to maintain it for financial reasons. Fortunately, there were more people waiting in the wings to fill Liverpool’s idle ships, this time willing passengers with an altogether brighter future in mind. It was the age of emigration to destinations such as America, Canada and Australia. Families looking for a new start came from across Britain, Ireland and Europe to Liverpool to take advantage of the numerous available passages and the relatively swift transatlantic journey. Consequently waves of people from many nations arriving or leaving Britain passed through the port. Apart from the wealth generated by ticket prices, there were associated benefits for the city in catering for this transient population. Accordingly businesses such as bars and boarding houses prospered, and as time went on so too did the railway system. In 1852 alone, almost 300,000 people left the Liverpool docks to start new lives in the Americas.

These peoples had an enormous impact on the city and its culture. Peter Grant, a local journalist, historian and specialist in all things Liverpudlian, was enlightening on the issue. ‘Scouse,’ he explained, ‘is an accent, a people and a dish.’

The first two are familiar, but the third is something of an unknown. Originally called Labskause, it turns out to be a mixed casserole dish of mutton and vegetables which had been brought to the city by Norwegian sailors. ‘The dish,’ said Peter, ‘is a perfect metaphor for Liverpool. You add a bit of this and a bit of that, then put in your spoon and mix. Much like the Scouse accent, which is made up of Scottish, Irish, Welsh, Lancashire and Cheshire accents, and according to where you are in the city it has its own distinct twang.’

By 1872 Liverpool was the national focus for emigration.

Liverpool Record Office

From Liverpool we headed east to Rainhill, just 20 minutes down the tracks. Steam trains expert Christian Wolmar waited on the station platform. Although noisy and not that pretty, Rainhill station seemed the most appropriate place for him to talk about what is perhaps the most significant stretch of railway line in the world. As trains thundered past, Christian explained that the first competition between steam locomotives had taken place here in 1829, before train and track were inextricably linked. Indeed, rails had been in existence for years, usually extending between mines or quarries and nearby industrial centres. Loaded wagons were usually pulled by horses. At the time of the contest the notion of an independently powered engine doing the donkey work was still new.

GEORGE STEPHENSON’S ROCKET WON HANDS DOWN, HAVING ACHIEVED A TOP SPEED OF 30 M.P.H.

It seems extraordinary now, but the 1829 Rainhill trials were organised to enable the directors of the Liverpool & Manchester Line to decide whether the trains should be powered by locomotives or by stationary steam engines. Five locomotives took part, one of which was powered by a horse walking on a drive belt, and were timed over the same course, with and without carriages. There was a £500 prize for the victor, whether or not a locomotive was eventually chosen. George Stephenson’s Rocket won hands down, having achieved a top speed of 30 m.p.h., and set a steam locomotive agenda for the Liverpool & Manchester Line, and ultimately the rest of the country. The display was enough to convince any remaining doubters that locomotives were the way forward as far as rail travel was concerned.

A year later the line was opened by the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington. But Stephenson’s day of triumph was marred by the death, not far from where we stood, of Merseyside MP William Huskisson, who became one of the first victims of the modern railway.

Huskisson accidentally opened a carriage door in front of the oncoming Rocket, was knocked off balance and fell beneath its wheels. Although the Conservative MP was rushed by train to the town of Eccles by Stephenson himself, he died there within a few hours. His untimely death gave ammunition to a stalwart band of nay-sayers who opposed the railway on the grounds that it was new, that it threatened long-established ways of life and that there were unknown dangers associated with it that had yet to become apparent. Iron roads were not welcome everywhere they went. But despite Huskisson’s demise it was apparent that the age of rail, indeed rail mania, was here to stay.

Stephenson’s Rocket was the winner of a steam locomotive competition held in rainhill in 1829 that determined a bright future for this new technology.

Stapleton Historical Collection/Photolibrary