По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

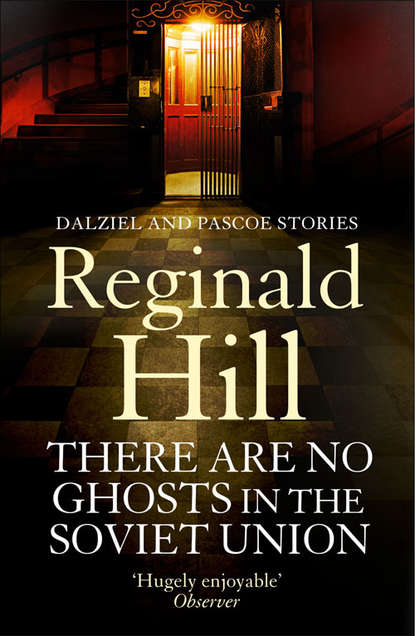

There are No Ghosts in the Soviet Union

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘This is an inquiry authorized by Comrade Secretary Serebrianikov of the Committee on Internal Morale and Propaganda,’ he declared baldly. Then after a pause to let the implications sink in, he made his request.

The promised return call came midway through the morning.

The Hotel Imperial no longer existed. Indeed it hadn’t really existed as the Hotel Imperial at all. Planned for completion at the end of 1914, its construction had been suspended at the outbreak of the war and it wasn’t actually finished till 1922. It occurred to someone shortly afterwards that Imperial was perhaps not the most suitable name for this revolutionary city’s most modern hotel, and the name was changed about the same time as Petrograd became Leningrad. It must have seemed a name for all time when they decided to christen it after the Father of the great Red Army and re-named it the L.D. Trotsky Building. The name survived Trotsky’s expulsion from the Party in 1927 – rehabilitation perhaps still seeming possible – but not his exile two years later, when it was rechristened, uncontroversially, the May Day Centre. During all these vicissitudes it was used as an administration and accommodation centre for visiting officials and delegations from all over the country. Moscow might be the official capital, but Leningrad was, and would always be, the historical centre of the great revolutionary movement …

Chislenko interrupted the threatened commercial brusquely. ‘And what happened to the place, whatever you call it, in the end?’

‘It was hit by German shells in 1943,’ came the reply in a rather hurt tone of voice.

‘Hit? You mean destroyed?’

‘It was rendered unusable, that’s what the records say.’

‘And it was never reconstructed as such.’

‘No, Comrade. That area of the city, like many others, was cleared and totally rebuilt in the great post-war reconstruction programme.’

‘Is there in the records a list of those who were in charge of that particular site in the clearance stage of the reconstruction programme?’

For the first time the MVD man in Leningrad let a hint of impatience sound in his voice.

‘We’ve no list as such, but I suppose I could go through the minutes and progress reports and see which names turn up.’

‘That would be kind. The Comrade Secretary would, I am sure, appreciate that,’ said Chislenko.

The names were soon forthcoming. In fact it wasn’t too long a list, and one name dominated the rest. Clearly this was the man on the ground who was in direct control of the day-to-day work.

Chislenko noted it without comment. He’d already written it down on his jotter with a large question-mark next to it. Now he crossed out the question-mark.

The name was Mikhail Osjanin.

6

That evening in Natasha’s apartment with the radio turned up high just in case he was right about KGB bugs, he told the girl about the two reports he had left in the Procurator’s office that afternoon.

One of them had been long and very detailed. This was the one which showed there was no possible historical basis for a ghost, then went on to give the new and revised accounts of events from Natasha, her mother, and Rudakov, ending with the conclusion that a combination of heat, fatigue, stale air and a little restorative alcohol had combined to make Josif Muntjan hallucinate so strongly that his hysteria had communicated itself to those around.

Chislenko then declared boldly that he could find no evidence of subversive intent and recommended that Muntjan should undergo a medical examination to test if he were fit for his job. If, as seemed likely, he failed this, he should then be pensioned off to be looked after by his niece who happened to be the supervisor’s wife.

Natasha whistled.

‘That’s bold of you, isn’t it?’

‘Is it?’

‘Yes. You could just have tossed him and the supervisor to the wolves, couldn’t you?’

‘Don’t think that I wasn’t going to do it,’ said Chislenko drily.

Then he told her about the second report.

It had been very short.

In it he said that it appeared that the lifts in the Gorodok Building had been manufactured in Chemnitz, Germany, in 1914 for the Hotel Imperial in St Petersburg. This building had been damaged in 1943 and the site had been cleared in 1945 under the supervision of M.R.S. Osjanin.

‘I don’t understand,’ said Natasha.

‘You would if you could see the photostat documents accompanying the other report. The full history of the Gorodok Building’s there. Plans, costing; material and machines; purchase, delivery; everything. All authorized and authenticated by the project director, who has since risen to the rank of Controller of Public Works, one Mikhail Osjanin.’

Natasha digested this.

‘You mean Osjanin was on the fiddle?’

‘Possibly,’ said Chislenko.

‘But a couple of lifts … how much would they cost, by the way?’

‘I forget the exact costing, but a lot of roubles,’ said Chislenko. ‘The point is, of course, how much else was there?’

‘Sorry?’

‘How much other material cannibalized from demolition sites and officially written off did Osjanin and his accomplices recycle into the reconstruction programme? And what else has he been up to? A fiddler rarely sticks to one fiddle!’

Natasha studied him earnestly.

‘This is dangerous, isn’t it?’ she said softly.

‘Could be. That’s why I’ve put these reports in separately. By itself the second one is pretty meaningless. I even left the old names in – Chemnitz, St Petersburg, the Hotel Imperial. You could drop it in a filing cabinet and no one would look at it for a hundred years. But set it beside the documents on the Gorodok Building attached to the other …’

‘I see. You make no accusations, draw no conclusions. That’s for someone else.’

She sounded accusing.

‘Right,’ he said.

‘And will conclusions he drawn?’

‘Osjanin’s a youngish man, mid-fifties. Rumour has it he feels ready for even higher things. It all depends whether Oscar Bunin, my MVD Minister, sees him as an ally or a threat. If he’s a threat, then Bunin will almost certainly set Serebrianikov on him.’

‘Otherwise he’ll get away scot-free?’ said Natasha indignantly.

‘Certainly,’ smiled Chislenko. ‘But, at least, giving the Comrade Secretary that has put me in credit enough to dare recommend that poor old Josif Muntjan gets let down lightly.’

She thought about this for a moment, then leaned forward and kissed him.

‘You’re a nice man, Lev Chislenko,’ she said.

‘No, I’m not,’ he said bluntly. ‘I’m a policeman.’