По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

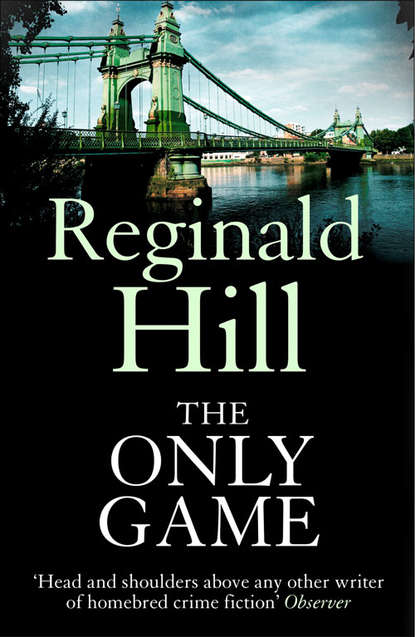

The Only Game

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘No real interest, Dog,’ said Tench with mock solemnity. ‘Nothing that I’d call an interest. Just that she’s on a little list of ours. People with a fine thread tied to their tails. Touch ’em and there’s a little tinkle in the guardroom, know what I mean?’

‘The computer?’ said Dog. ‘I wondered why that entry was there. Anyone asking questions jerks the trip wire, right?’

‘Clever boy,’ said Tench. ‘So tell me all you know.’

Briefly, Dog outlined his investigation so far.

Tench produced a notebook, not to make notes in but to examine.

‘Well done,’ he said at the end of the outline. ‘Missed out nothing.’

‘You’ve spoken to Parslow? You knew all this! What the hell are you playing at? Checking up on me or what?’

‘Hold your horses, my son,’ said Tench earnestly. ‘Not you. Old Eddie Parslow, he’s the one we need to double check. He’s so demob happy, he’s stopped taking bribes.’

The muscular boy came out of the bedroom. In his hand was a foolscap-size buff envelope.

‘Found this in the mattress cover, guv,’ he said, handing it over.

‘Well done, my son,’ said Tench, smiling fondly.

‘You want I should organize a real search, guv?’ asked Stott.

Dog Cicero had no doubt what a real search meant. He’d supervised enough in scruffy Belfast terraces and lonely country farms, watching as floorboards were ripped up, tiles stripped, walls probed, while all around women wailed their woe or screamed abuse, and men stood still as stone, their faces set in silent hate.

Tench shook his head.

‘Early days, Tommy. Just carry on poking around.’

Tommy went into the kitchen. A second later what sounded like the contents of a cutlery drawer hit the tiled floor.

Tench was peering into the envelope.

‘What’s in it?’ asked Dog.

‘Not a lot. Hello. Must be saving for a rainy day. Well, the poor cow’s got her rain. Bet she’d like to get her hands on her savings!’

He tossed a smaller envelope across to Dog. He opened it. It was full of bank notes, large denomination dollar bills and sterling in equal quantities, at least a couple of thousand pounds’ worth.

‘Can see what you’re thinking, Dog. That’s a lot of relief massage. Maybe she upped her prices for more demanding punters. Any complaints about queues forming on the stairs?’

He looked at Dog with his head cocked to one side, like a jolly uncle encouraging a favourite nephew.

‘No,’ he said. ‘Nothing like that. Not so for.’

The last phrase was an attempt to compensate for what had come out as a rather over-emphatic denial.

Tench caught the nuance, said, ‘You don’t think she gives the full service then? Just the odd hand job for pocket money?’

‘I don’t know. I just don’t like running too far ahead of the evidence, that’s all.’

‘Oh yeah? Of course, she’s Irish, isn’t she?’

‘What’s that got to do with anything?’

‘Quite a lot, as it happens, my son. But in your case, it could mean you’re so desperate to put the slag away that you’re falling over backwards to be fair. You never were much good at thumping people just because you didn’t like them, Dog. Always had to find a reason! You’ll not admit it, but what you’d really like is solid evidence that she’s topped her little bastard, then you can go after her full pelt! Well, you can relax, my boy. Uncle Toby is here to tell you it’s going to be all right. It doesn’t matter if she’s cut his throat or she’s the loveliest mum since the Virgin Mary. You’re allowed to hate her guts either way!’

Dog was half out of his chair. One part of his mind was telling him to sit down and laugh at this provocation. The other was wondering how much damage he could inflict before Tommy, the gorgeous hulk, broke him in two.

Tench wasn’t smiling now.

‘Down, Dog. Down. If you don’t like a joke, you shouldn’t have joined. Man who’s not in charge of himself ain’t fit to be in charge of anything.’

Slowly Dog relaxed, sank back into the armchair.

‘That’s better. Godalmighty, just think, if you’d stayed in the Army, you’d have had your own company by now, maybe your own battalion. You’d have been sending men out where the flak was flying. Few more like you, and I reckon we’d have lost the Falklands. Still, not to worry, just think of the money we’d have saved!’

Dog said steadily, ‘Don’t you think it’s time you put me in the picture, sir. You called the boy a bastard. I presume you were being literal rather than figurative.’

‘I love it when you talk nice, Dog. Shows all that time in the officers’ mess wasn’t wasted. But yes, you’re dead right. Bastard he is, or was. One thing we know for sure, Maguire never got married. How do we know? Well, Oliver Beck was never divorced, was he? Let me fill you in, old son. After she jacked in the teaching, our Jane got herself a job with a shipping line, recreational officer they called it. On one Atlantic crossing she came in contact with an American passenger, Mr Oliver Beck. On the massage table, I shouldn’t wonder! Anyway, he was so impressed with her technique, he set her up in his house on Cape Cod. Oliver was living apart from his wife, natch.’

‘So it was more than just a bit on the side for him?’ interrupted Dog.

‘Why do you say that?’

‘He took her into his home. They had a child.’

‘Rather than setting her up in a flat and having an abortion? You could be right, Dog. Or maybe he just wanted a son and heir and didn’t much mind who the brood mare was. We don’t know just how close they really were, and it’s of the essence as you’ll see if you sit stumm for a few minutes. They certainly stuck together for the next five years. On the other hand he was away a lot and a live-in fanny probably comes as cheap as a live-in nanny. To cut a short story shorter, last April Oliver Beck snuffed it. He was a sailing freak, always shouting off he could’ve done the round-the-world-single-handed if he’d only had the time. This time he didn’t get out of Cape Cod Bay before a storm tipped him over, and put the Atlantic where his mouth was. Now came crunch time for our Janey. Who’d inherit?’

He paused dramatically. Dog said, ‘I thought this was the short version.’

‘Satire, is it?’ twinkled Tench. ‘All right. Well, it certainly wasn’t Maguire. There was no will and in less time than it takes to say conjugal rights, the real Mrs Beck came swanning in to claim everything. At least she wanted to, only at just about the same time, the Internal Revenue boys turned up too, and they were claiming everything times ten for unpaid taxes. Our Janey summed up the situation pretty well. There was nothing in it for her, so she upped sticks and headed for home, taking with her every cent she could lay her hands on plus everything portable in terms of jewellery, objets d’art et cetera. Only thing was, none of it belonged to her officially, and if she shows her face again back in Massachusetts she’ll find a warrant for her arrest waiting.’

He looked at Dog as though inviting a comment.

‘She was in a tough situation,’ he said. ‘She was entitled to something, surely.’

‘You reckon? Still falling backwards to be fair, are we, Dog? Even though this lady has an undeniable tendency to violence, an undeniable tendency to help herself to what ain’t hers, and an undeniable tendency to pull men’s plonkers for pocket money? Jesus, Dog, it’s the priesthood you should have turned to, not the police!’

‘You still haven’t said what your interest is, sir,’ said Dog.

‘Haven’t I? Neither I have! The thing is this, Dog. It wasn’t just the IRS who were keeping a friendly eye on Oliver Beck. It was the FBI. You see – this’ll slay you, Dog – it appears that one of the many shady ways that Beck earned his crust was by acting as a bagman for Noraid. I knew you’d like it! Now no one knows how much Janey was involved but one thing’s sure, she can’t have been ignorant. So now you can really let all that nasty bubbling hate go free, my son. You see, the money that kept that slag in silk knickers, maybe even those nice crisp folders you’ve got in your hand, all came from his commission moving the cash which bought the Semtex that cut your shaving bills in half for the rest of your natural life!’

10 (#ulink_a4c5f090-8eb7-54a6-9a66-ae150cc7ffd8)

Jane Maguire stood in a telephone kiosk in Basildon town centre. She could have been anywhere. One of the new towns built after the war to ease the pressure on London, its designers probably comforted themselves with the thought that a couple of hundred years would give it the feel of a real place. But in the decades that followed, up and down the country they had ripped the guts out of towns and implanted pedestrian precincts lined with exactly the same shops that she was looking at here. Why let the new grow old gracefully when you can make the old grow young grotesquely?

The thought wasn’t hers but standing here brought it back to mind, and the dry amused voice that spoke it. She longed to hear it now at the end of the phone, but the ringing went on and on. Abruptly she replaced the receiver.