По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

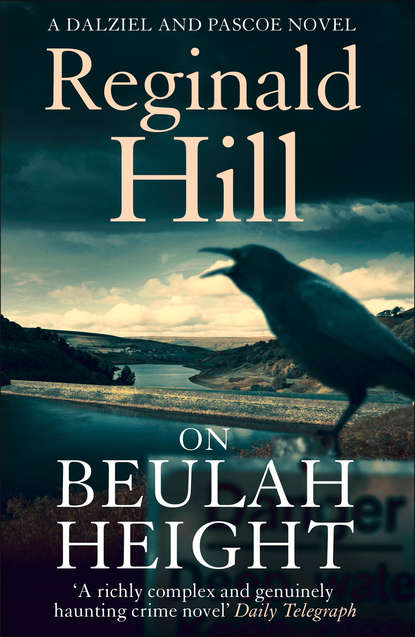

On Beulah Height

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The years had been good to Arne Krog. Into his forties now, his unlined open face framed in a shock of golden hair and a fringe of matching beard kept him looking more like Hollywood’s idea of a sexy young ski-instructor than anyone’s idea of a middle-aged baritone. And if, in terms of reputation and reward, the years had not been quite so generous, he made sure it didn’t show.

She said, ‘Most of what you said was right. Makes you happy, does it?’

She spoke with a strong Yorkshire inflexion which came as a surprise to those who knew her by her singing voice alone.

‘It makes me happy that you have seen your error. Never mind. It will be a collector’s disc when you are old and famous. Perhaps then, to be contrary, you will make your last recording of songs best suited to a young, fresh voice. But preferably in the language in which they were written.’

‘I wanted folk to understand them,’ she said.

‘Then give them a translation to read, not yourself one to sing. Language is important. I should have thought someone so devoted to her own native woodnotes wild would have understood that.’

‘Don’t see why I should have to speak like you just to please some posh wankers,’ she said.

She smiled briefly as she spoke. Her face with its regular features, dark unblinking eyes, and heavy patina of pale make-up, all framed in shoulder-length ash blonde hair, had a slightly menacing mask-like quality till she smiled, when it lit to a remote beauty, like an Arctic landscape touched by a fitful sun. She was five nine or ten, and looked even taller in the black top and lycra slacks which clung to her slim figure.

Krog’s eyes took this in appreciatively, but his mind was still on the music.

‘So you will change your programme for the opening concert?’ he said. ‘Good. Inger will be pleased too. The transcription for piano has never been one she liked.’

‘She talks to you, does she?’ said Elizabeth. ‘That must be nice. But chuffed as I’d be to please our Inger, it’s too late to change.’

‘Three days,’ he said impatiently. ‘You have the repertoire and I will help all I can.’

‘Thanks,’ she said sincerely. ‘And I’d really like your help to get them right. But as for changing, I mean it’s too late in here.’

She touched her breastbone.

He looked exasperated and said, ‘Why are you so obsessed with singing these songs?’

‘Why’re you so bothered that I’m singing them?’

He said, ‘I do not feel that, in the circumstances, they are appropriate.’

‘Circumstances?’ She looked around in mock bewilderment. They were in the elegant high-ceilinged lounge of the Wulfstans’ town house. French windows opened on to a long sunlit garden. Faintly audible were the rumbles of organ music under the soaring line of young voices in choir. If they’d stepped outside they could have seen a very little distance to the east the massive towers of the cathedral whose gargoyled rain-spouts seemed to be growing ever longer tongues in this unending drought.

‘Didn’t think you got circumstances in places like this,’ said Elizabeth.

‘You know what I mean. Walter and Chloe …’

‘If Walter wanted to complain, he’s had the chance and he’s got the voice,’ she interrupted.

‘And Chloe?’

‘Oh aye. Chloe. You still fucking her?’

For a moment shock time-warped him to his early forties.

‘What the hell are you talking about?’ he demanded, keeping his voice low.

‘Come on, Arne. That’s one English word no one needs translating. Been going on a long time, hasn’t it? Or should I say, off and on? All that travelling around you do. Must be great comfort to her you don’t let yourself get out of practice, but. Like singing. You need to keep at your scales.’

He had recovered now and said with a reasonable effort at lightness, ‘You shouldn’t believe all the chorus-line gossip you hear, my dear.’

‘Chorus line? Oh aye, I could give Chloe enough names to sing the Messiah.’

He said softly, ‘What’s the point of this, Elizabeth? What do you want?’

‘Want? Can’t think of owt I want. But what I don’t want is Walter getting hurt. Or Chloe.’

‘That is very … filial of you. But you work very hard at that role, don’t you? The loving, and beloved, daughter. Though in the end, alas, as with all our roles, the paint and wigs must come off, and we have to face ourselves again.’

He spoke with venom, but she only grinned and said, ‘You sound like you got out the wrong side of bed. And you were up bloody early too. Man of your age needs his sleep, Arne.’

‘How do you know how early I got up? Am I under twenty-four hour surveillance then?’

‘Woke with the light myself, being a country lass,’ she said. ‘Heard your car.’

‘It could have been someone else’s.’

‘No. You’re the only bugger who changes up three times between here and end of the street.’

He shrugged and said, ‘I was restless, the light woke me also. I wanted to go for a walk, but not where I’d be surrounded by houses.’

‘Oh aye? See anyone you know?’

He fingered the soft hair of his beard into a point beneath the chin and said, ‘So early in the day I hardly saw anyone.’

She said, ‘Give us a knock next time, mebbe I’ll come with you. Listen, now you’re here, couple of things in the Mahler you can help me with.’

He shook his head wonderingly and said, ‘You are incredible. I tell you, I think you made a mistake to sing these songs on your first recording and that you will be making another to sing them at the concert. You ignore my advice. You make outrageous accusations, and now you want me to help you to do what I do not think you should be doing anyway!’

‘This isn’t personal, Arne. This is about technique,’ she said, sounding puzzled he couldn’t make the distinction. ‘I might think you’re a bit of a prick, but I’ve always rated you a good tutor. Mebbe that’s what you should have gone in for instead of performing. Now listen, I’m a bit worried about my phrasing here.’

She pressed her zapper and the song resumed.

‘Oh, yes, they’ve only gone out walking,

Returning now, all laughing and talking.

Don’t look so pale! The weather’s bright.

They’ve only gone to climb up Beulah Height.’

‘You hear the problem?’ she said, pressing pause again.

‘Why did you say up Beulah Height?’ he demanded. ‘That is not a proper translation. The German says auf jenen Höh’n.’

‘All right, keep your hair on. Let’s say on yonder height, that keeps the scansion,’ she said impatiently. ‘Now listen, will you?’