По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

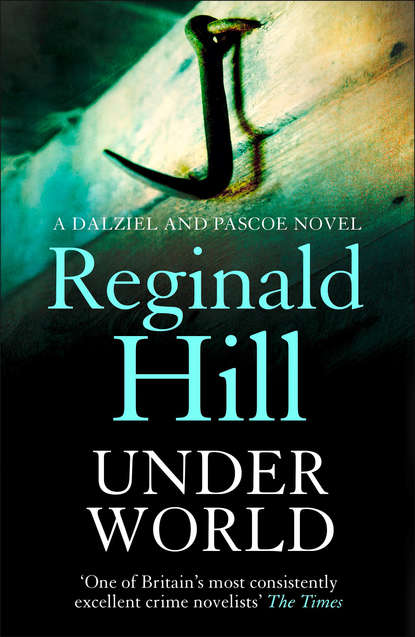

Under World

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘What?’ he demanded.

‘Nowt. Just thought there weren’t much point ruining me fingernails digging if you’d snuffed it,’ said Dalziel. ‘How are the legs? Still hurting?’

‘The pain seems to be getting further away,’ whispered Pascoe. ‘Or perhaps it’s just the legs that are getting further away.’

‘Jokes, is it? What are you after, lad? The fucking Police Medal?’

‘No joke, sir. More like despair.’

‘That’s all right, then. One thing I can’t stomach’s a bloody hero.’

Dalziel belched as though in illustration and added reflectively, ‘I could stomach one of Jack’s meat pies from the Black Bull, though.’

‘Food,’ said Pascoe.

‘You peckish too? That’s hopeful.’

‘Another good sign?’ whispered Pascoe. ‘No. I meant there wasn’t any. Back at the White Rock. Did you see any?’

‘Likely he’d not unpacked it. Well, he wouldn’t have time, would he?’

‘Perhaps not … there was someone in there, you know …’

‘In where? The White Rock? In a cave, or what?’

‘Back there … the side gallery … someone, something … I can’t remember …’

‘In there, you mean? Of course there was. Young bloody Farr was in there, which is why we’re in here, up to our necks! Well, back to work.’

It wasn’t the answer or at least only part of it, but his mind seemed to be refusing to register much since they had so foolishly left that marvellous world of air and trees and space and stars. He gave up the attempt at recall and lay still, listening to the fat man’s rat-like scrabblings. Was it really worth it? he wondered. He didn’t realize he’d spoken his thought, but Dalziel was replying.

‘Likely not. They’re probably out there already with their shovels and drills and blankets and hot soup and television lights and gormless interviewers practising their daft bloody questions. Nay, I’m just doing this to keep warm. Sensible thing would be to lie back and wait patiently, as the very old bishop said to the actress.’

‘How will they know where we are?’

‘You don’t think them other buggers got stuck like us? Pair of moles, them two. Born with hands like shovels and teeth like picks, these miners. I can’t wait to get my hands on that young bastard, Farr. This is all down to him, running off down here. Bloody Farr. He’ll wish he were far enough when I next see him.’

Pascoe smiled sadly at the fat man’s attempted cheeriness. He didn’t believe that he and Colin Farr would ever meet again. His mind burrowed into the huge pile of earth and rock which held him trapped and his heart showed him Colin Farr trapped there too. Or worse. And if worse, how to explain it to Ellie in the unlikely event he ever got the chance? Any explanation must sound like justification. He would, of course, deny any imperatives other than duty and the law. Up there you had to keep things simple. There was no other way to survive.

But down here survival was too far beneath hope to make a motive, and the darkness was fetid with doubt and accusation. Time for the bottom line, as the Yanks put it. Place for a bottom line too. And the bottom line read like this.

Colin Farr. Trapped by the pit he hated. Driven into that trap by a man who hated him.

Colin Farr.

Part One (#ulink_93fc55d3-95e8-561b-a090-9ca2cbef0683)

And see! not far from where the mountain-side

First rose, a Leopard, nimble and light and fleet,

Clothed in a fine furred pelt all dapple-dyed,

Came gambolling out, and skipped before my feet.

Chapter 1 (#ulink_56e8ea64-b74a-5035-bf1e-e928aefa4d0a)

‘… the paddy broke down and we had to walk nearly the full length of the return to pit bottom and there was a hell of a crowd there already and tempers were getting frayed. They usually do if you’re kept waiting to ride the pit, especially when other buggers push into the Cage ahead of you because they’ve got priority. It’s not so bad when it’s the wet-ride – that’s men who’ve been working in water – though even then there’s a lot of complaining and the lads yell things like, “Call that wet? I think tha’s just pissed on tha boots!” But worst of all is when a bunch of deputies get to ride ahead of you which is what happened to us, and the sight of all those clean faces, grinning like they were getting into a lift in a knocking shop, really got our goat. As the last one got in, someone yelled, “That’s right, lad, hurry on home to your missus. But you’ll not get to ride there before the day-shift!” The deputy’s face were white before, but now it got even whiter and he set off back out of the Cage like he was going to grab whoever it was that called out and start a rumpus, but some of the other officials got hold of him and the grille clanged shut and the Cage went up. Mebbe it shouldn’t have been said, but first thing you learn down pit is not to bite when someone tries to rile you, and it certainly cheered up most of the poor sods still left waiting.

‘I rode up with the next lot and that was the end of my shift and this is the end of my homework.’

‘Thank you, Colin,’ said Ellie Pascoe. ‘That was really very good.’

‘Ee, miss, tha don’t say? Dost really think there’s hope tha can learn an ignorant bugger like me to read and write proper?’

Colin Farr’s accent had broadened beyond parody while his mouth gaped and his eyes bulged into a mask of grotesque gratitude. The others in the group roared with laughter and Ellie found herself flushing with shame at the justified rebuke; but because she was by nature a counter-puncher, she replied, once again without thinking, ‘Perhaps I’ll settle for learning you to stop feeling insecure in unfamiliar situations.’

Farr’s features tightened to their usual expression of amused watchfulness.

‘That’ll be grand,’ he said. ‘As soon as you’ve found the secret, be sure to let me know.’

He’s right, thought Ellie miserably. I’m as insecure as any of them!

She hadn’t anticipated this three weeks earlier when Adam Burnshaw, director of Mid-Yorks University’s extra-mural department, had rung to ask if she could help him out. One of his lecturers had contracted hepatitis in the Urals (Ellie had observed her husband teeter on the edge of a Dalzielesque joke), leaving a gap in a union-sponsored day-release course for miners. Ellie, politically sound, with years of experience as a social science lecturer till de-jobbed by childbirth and redundancy (both fairly voluntary), was the obvious stop-gap. No need to worry about her daughter, Rose. The University crèche was at her disposal.

Ellie had needed little time to think. Though far from housebound, she had started to feel that most of her reasons for going out were short on moral imperative. As for her reason for not going out, the great feminist novel she was supposed to be writing, that had wandered into more dead ends than a walker relying on farmers to maintain rights-of-way.

Preparation had been a bit of a rush, but Ellie had not stinted her time.

‘This is something worthwhile,’ she assured her husband. ‘A real job of real education with real people. I feel privileged.’

Peter Pascoe had wondered over his fourth consecutive meal of tinned tuna and lettuce whether in view of her messianic attitude to her prospective students, she might not be able to contrive something more interesting with leaves and fishes, but it was only a token complaint. Lately he too had started noticing signs of restlessness and he was glad to see Ellie back in harness, particularly in this area. During the recent year-long miners’ strike, when relations between police and pickets came close to open warfare, she had kept as low a profile as she could conscientiously manage. This had cost her much political credibility in her left-wing circles, and this job-offer from academic activist, Burnshaw, was like a ticket of readmittance to the main arena.

But there’s no such thing as a free ticket. The dozen miners who turned up at her first class on Industrial Sociology seemed bent on confirming the judgement of Indignant (name and address supplied) in the letter columns of the Evening Post, that such courses were little more than subsidized absenteeism.

At the end of an afternoon of monosyllabic responses to her hard prepared but softly presented material, she had retired in disarray after issuing a schoolmarmly invitation to write an account of a day at work before the next encounter.

That night she served frozen pizza as a change from tuna.

‘How’d it go, then?’ asked Pascoe with a casualness she mistook for indifference.

‘Fine,’ she grunted with a laconicism he mistook for exclusion.

‘Good. Many there?’

‘Just twelve.’

‘Good number for a messiah, but watch out for Judas.’