По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

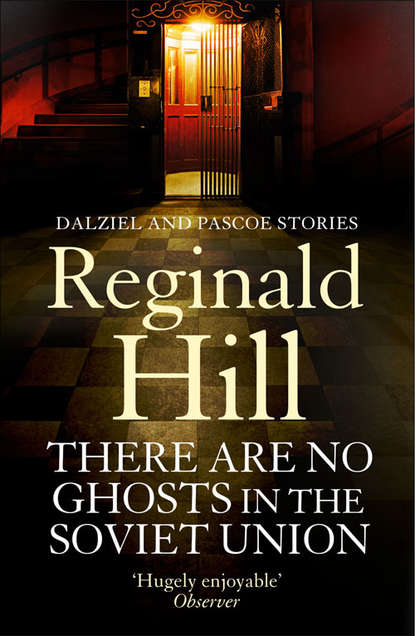

There are No Ghosts in the Soviet Union

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘The clothes?’ He cast his mind back to the witness statements. ‘Yes, I recall, there was something about an old-fashioned suit. But, good lord, Moscow’s full of old-fashioned suits! Who can afford a new-fashioned suit these days?’

The question was rhetorical since any attempt to answer it would almost certainly have involved a slander of the State.

She said, ‘It was more than that. It was, well, a new old-fashioned suit, if you follow me. And he was wearing a celluloid collar too. Now, old-fashioned suits may be plentiful still, but you don’t see many celluloid collars about, do you? And he had button-up shoes!’

‘Now there’s a thing!’ said Chislenko. ‘So what kind of dating would you put on this outfit?’

She pursed her lips thoughtfully. It would have been very easy to lean forward and kiss them but Chislenko was not letting himself relax that far. Not yet anyway; the thought popped up unexpectedly, surprisingly, but not unwelcomely.

‘’Thirties, late ’twenties, somewhere around then, I’d say,’ she said.

He laughed out loud and said, ‘Now that is interesting. When you go to work in the morning do you ever look up?’

‘Look up?’ She was puzzled.

‘Yes, up.’ He raised his head and his eyes till he was looking at the angle where the yellowing paper on the walls met the flaking whitewash on the ceiling. ‘Or is it head down, eyes half closed, drift along till you reach your desk?’

‘I’m very alert in the mornings,’ she retorted spiritedly.

‘I’m glad to hear it. Then you must have noticed that huge concrete slab above the main door. The one inscribed. The Gorodok Building. Dedicated to the Greater Glory of the USSR and opened by Georgiy Malenkov in June 1949.

‘Nineteen forty-nine,’ she echoed. ‘Oh. I see. Nineteen forty-nine.’

‘Yes. Part of our great post-war reconstruction programme,’ he said, rising. ‘A little late for celluloid collars and button-up shoes, don’t you think? Thank you for the tea, Comrade Natasha. I’m sure we’ll meet again, I’ll need to keep in touch with you till this strange business is settled.’

He offered his hand formally. She shook it and said, ‘And I’ll be very interested to learn how you manage to settle it, Comrade Inspector.’

He smiled and squeezed her hand. She returned neither squeeze nor smile. He didn’t blame her. Only a fool would allow a couple of minutes’ friendly chat to break down the barriers of caution and suspicion which always exist between public and police.

And Natasha, he guessed, was no fool.

Checking Josif Muntjan, the liftman, wasn’t half as pleasant but just as easy. The State makes no social distinction in its records. Menial or master, once you come into its employ, you get the womb-to-tomb X-ray treatment.

Muntjan came out pretty clear. There was a record of minor offences, all involving drunkenness, but none recent, and nothing while on duty.

Indeed, the supervisor, who didn’t look like a man in whom the milk of compassion flowed very freely, spoke surprisingly well of him. He expressed surprise rather than outrage at the mention of the hip-flask.

‘It’s not an offence to own one, is it?’ he said. ‘No need to report it, though, is there? I’ll see he doesn’t bring it to work with him again. He’ll take notice of what I say. Jobs aren’t easy to come by when you’re old and unqualified.’

Chislenko nodded; the man’s sympathetic understanding touched him. He clearly knew that if Muntjan were tossed out of his job, he probably wouldn’t stop falling till he landed in one of those shacks on the outer ring road where the Moscow down-and-outs eked out their perilous existence. Or rather, non-existence, for of course in the perfect socialist state, such degraded beings were impossible.

Crime too was impossible. Or would be eventually. The statistics showed progress. Chislenko defended the statistics as fervently as the next man, knowing that if he didn’t, the next man would probably report the deficiency. But falling though the crime rate might be, there was still a lot of it about and Chislenko resented the amount of time he had to spend on this unrewarding and absurd business at the Gorodok Building. The only profit in it was that it had brought him into contact with Natasha Lovchev, but that relationship was still as uncertain in its outcome as a new Five-Year-Plan.

He turned his attention from Muntjan to Alexei Rudakov. Here the computer confirmed his own first estimate. Rudakov was a man to be treated with respect. Only his initial foolishness in leaving the scene of the incident made him vulnerable to hard questioning. The trouble was, the harder the questioning, the firmer his story.

Finally Rudakov said, ‘Comrade Inspector, clearly you want to hear this story as little as I want to tell it. In a few days I shall be returning to the Dnieper Dam. Rest assured, I shall not be making a fool of myself by repeating this anecdote there. In other words, if you stop asking questions, I’ll stop giving answers!’

It made good sense to Chislenko. The best way to deal with this absurd business was to ignore it. He only hoped his superiors would agree, and he gave them their cue by writing a final dismissive report, this time risking a conclusion couched in the kind of quasi-psychological jargon Natasha had mockingly used.

Then he crossed his fingers, and waited, and even said a little prayer.

The authorities were right to ban religion.

The following day he was summoned to Procurator Kozlov’s office.

3

Of all the deputy procurators working in the Procurator General’s office, Kozlov was the one most feared. Unambiguously ambitious, he took lack of progress in any case under his charge as an act of personal sabotage by the Inspector involved, and his own advancement was littered with the wrecks of others’ careers. His legal career had begun in the attorney’s department of the Red Army, and on formal official occasions Kozlov always wore the uniform of colonel to which his military service entitled him.

He was wearing the uniform today. It was not a good sign.

So preoccupied was Chislenko by this sartorial ill-omen that at first he did not notice the other person in the room. It was only when he came to attention and focused his eyes over the seated Procurator’s head that he took in the unexpected presence. Standing by the window looking down into Petrovka Street was an old gentleman (the term rose unbidden into Chislenko’s mind), with a crown of snow white hair, a goatee beard of the same hue, cheeks of fresh rose, eyes of bright blue, and an expression of almost saintly benevolence.

Procurator Kozlov did not look benevolent.

‘Inspector Chislenko,’ he rasped. ‘This business of the Gorodok Building. These are your final reports?’

He stabbed at the file on his desk.

‘Yes, sir,’ said Chislenko.

‘And you recommend that no further inquiry is needed?’

‘I can see no line of further inquiry that might be useful,’ said Chislenko carefully.

The Procurator sneered.

‘No line which might be fruitful if pursued in the indolent, incompetent and altogether deplorable manner in which you’ve managed this business so far, you mean!’

The unexpected violence of the attack provoked Chislenko to the indiscretion of a protest.

‘Sir!’ he cried. ‘I resent your implications …’

‘You resent!’ bellowed Kozlov, his smart uniform stretching to the utmost tolerance of its stitching.

‘Comrades,’ said the old man gently.

The speed with which the Procurator deflated made Chislenko look at the old gentleman with new eyes. Wasn’t there something familiar about those features?

‘Let us not be unfair to the Inspector,’ he continued with a friendly smile. ‘He has done almost as much as could be expected, and his desire to let this matter die quietly is altogether laudable. However …’

He paused, came to the desk, picked up the file and sifted apparently aimlessly through its sheets.

‘Do you know who I am, Inspector?’ he said finally.

Desperately Chislenko searched his memory while the old man smiled at him. Honesty at last seemed the best policy.

‘My apologies, Comrade,’ he said. ‘There is something familiar about you but I cannot quite find the name to go with it.’