По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

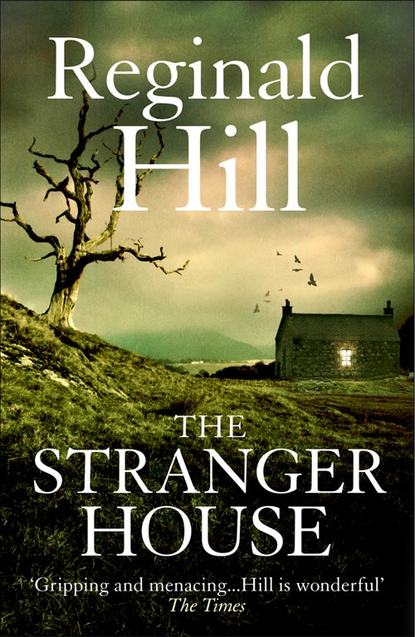

The Stranger House

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Worse than you. Had to be a compliment in there somewhere, thought Sam.

‘Then thank you so much.’

‘Think nowt of it,’ said the woman. ‘Enjoy the church. See you later. Don’t forget your sandwich.’

‘Won’t do that in a hurry. See you later!’

Outside, she found the drizzle which had accompanied her most of the way from London seemed at last to have given up. She reached into her hired car parked on the narrow forecourt and opened the glove compartment. There were three Cherry Ripes in there. She’d been incredulous when Martie, whose gorgeous looks had earned her more air miles than most Qantas pilots by the time she left uni, had told her you couldn’t get them outside of Oz. Life without a daily injection of this cherry-and-coconut mix in its dark chocolate wrapping had seemed impossible and she’d stuffed a month’s supply into her flight bag. Unfortunately the ravages of Heathrow Customs had been followed by the rapine of the Aussie friends she’d stayed with in London, and now she was down to her last three. She slipped two of them into her bumbag, one to eat on her walk to the church, one for emergencies.

Then she took one of them out and replaced it in the compartment.

Knowing yourself was the beginning of wisdom, and she had still to find a way of not consuming every bit of chocolate available once she started.

The landlady had followed her to the front door. In case she’d noticed the business with the Cherry Ripes, Sam held up the cob and nibbled appreciatively at one of the dangling skirts of ham. Then with the Illthwaite Guide tucked under one arm, she set off along the road.

Mrs Appledore stood and watched her guest out of sight, then turned and went back into the Stranger House, slipping the bolt into the door behind her. In her kitchen she lifted the telephone and dialled. After three rings, it was answered.

‘Thor, it’s Edie,’ she said. ‘Something weird. I’ve got a lass staying here, funny little thing, would pass for a squirrel if you glimpsed her in the wood, skin brown as a nut, hair red as rowan berries. Looks about twelve, but from her passport she’s early twenties…Don’t interrupt, I’m coming to the point. Her name’s Sam Flood…That’s right. Sam for Samantha Flood, it’s in her passport. She’s from Australia, got an accent you could scratch glass with, and she thinks her grandmother might have come from these parts…1960, spring…Yes, ‘60, so it’s got to be just coincidence, but I thought I’d mention it. She’s off up to the church to see if there’s any records…Yes, I’ll be there, but not till he’s well screwed down. I’ll take your word the little bugger’s dead!’

2 a turbulent priest (#ulink_aafcbe4a-7fb7-55a1-abf0-fa2c140e35a0)

Sam Flood and Miguel Madero saw each other for the first time in a motorway service café to the west of Manchester but neither would ever recall the encounter.

Sam was sitting at a table with a double espresso and a chocolate muffin which was far too sweet but she ate it anyway. She glanced up to see Madero passing with a cappuccino and a cream doughnut. Though he wore no clerical collar, there was something about him—his black clothing, the ascetic thinness of his face—which put her in mind of a Catholic priest, and she looked away. For his part all he registered was an unaccompanied child whose exuberance of red hair could have done with a visit to the barber, but most of his attention was focused on maintaining the delicate relationship between an unreliable left knee and an overfull cup of coffee.

She left five minutes before he did and they spent the next hour only a couple of miles apart in heavy traffic. Then a van blew a tyre a hundred yards behind her and spun into a truck. Miraculously no one was seriously hurt, but as Sam’s Focus sped merrily north, Madero and his Mercedes SLK fumed gently in the accident’s tailback.

From having time to spare for his two o’clock appointment in Kendal, he was already half an hour late as he reached the town’s southern approaches.

On the map Kendal looked to be a quiet little market town on the eastern edge of the English Lake District, but there seemed to be some local law requiring all traffic in Cumbria to pass along its main street, which meant it was after three when he drew up before the chambers of Messrs Tenderley, Gray, Groyne, and Southwell, solicitors.

Knowing how highly lawyers price their time, he was full of apology as he was shown into the office of Andrew Southwell.

‘Not at all, not at all, think nothing of it,’ said Southwell, a small round man in his early thirties who pumped his hand with painful enthusiasm. ‘I’ve been looking forward to meeting you. Dr Coldstream speaks very warmly of you. Very warmly indeed.’

‘And of you too,’ said Madero.

In fact what Max Coldstream had said when he mentioned Kendal was, ‘You’re in luck there, Mig. Chap called Southwell, Kendal solicitor, and mad keen local historian. OK, so he’s an amateur, but that can be an advantage. Professional historians on the whole are a deceitful, distrusting, conniving and secretive bunch of bastards who would direct a blind man up a blind alley rather than risk giving him an advantage. Enthusiastic amateurs on the other hand may lack scholarship but they often have bucketloads of information which they are eager to share. Painfully eager, if you’re in a hurry!’

It only took a couple of minutes for Madero to appreciate Coldstream’s warning.

‘That’s fascinating, Mr Southwell,’ he said, interrupting a potted history of the chambers building. ‘Now, you will recall from my letter I’m on my way to talk to the Woollass family of Illthwaite Hall in connection with my thesis on the personal experience of English Catholics during the Reformation. By chance I came across a reference to a Jesuit priest, Father Simeon Woollass, the son of a cadet branch of the family residing here in Kendal. I thought it might be worth diverting to see what I could find out about him. A priest in the family must have made the problems of recusancy even greater, as perhaps your researches have already discovered.’

This was the right trigger to pull.

Southwell nodded vigorously and said, ‘How very true, Mr Madero. But I know you chaps, hands-on whenever possible, so let’s take a walk and see what we can find.’

Next moment Madero found himself being whizzed down the stairs, past the receptionist who desperately shouted something about not forgetting the partners’ meeting, and out into the damp afternoon air, where he was taken on a whirlwind tour.

‘It’s curious,’ said Southwell as they raced from the library to the church. ‘What really got me interested in Father Simeon wasn’t you, but this other researcher who was asking questions, must be ten years ago now. Irish chap, name of Molloy. Poor fellow.’

‘I don’t recognize the name. Did he publish? And why do you say “poor fellow”?’

‘He did a few things, pop articles mainly. Not a serious scholar like you, more of a journalist. But nothing on Father Simeon. Never had the chance really. He was something of a rock climber, took the chance to do a bit while he was up here, by himself, very silly, and he had this terrible accident…are you all right, Mr Madero?’

‘Yes, fine,’ lied Mig. Twinges in his still unreliable left knee he was used to, but the other injuries he’d suffered in his own fall rarely troubled him now. This lightning jag of pain across his head and down his spine had to be some kind of sympathetic echo. In fact during his own fall he couldn’t even remember the pain of contact…

‘You sure?’ said Southwell.

‘Yes, yes,’ said Mig impatiently as the pain faded. ‘And he was killed, was he?’

‘Died as the Mountain Rescue carried him back. He wasn’t so much interested in the background as in what happened when Father Simeon got captured. The book he was writing was actually about Richard Topcliffe—you know about him, of course?’

‘Elizabeth’s chief priest-hunter, homo sordidissimus. Oh yes, I know about him.’

‘Well, it was Topcliffe’s northern agent, Francis Tyrwhitt, who captured Simeon and took him off to Jolley Castle near Leeds to be interrogated. That was Molloy’s main interest, torture, that kind of stuff. Ah, here’s the church. Note the Victorian porch.’

It was clear that, despite his conviction that academics preferred to do their own research, Southwell had already dug up everything there was to dig up about Simeon and recorded it in the folder he carried. Madero was tempted but too polite to suggest that a lot of time could be saved if he simply handed it over. Happily after a couple of hours the man’s mobile rang. He listened, then said, ‘Good Lord, is it that time already?’

To Madero he said, ‘Sorry. Meeting. Lot of nothing, but old Joe Tenderley, our senior partner, tends to get his knickers in a twist. Look, why don’t we meet up later? Better still, have dinner, stay the night. Meanwhile you might care to browse through my notes, see if there are any gaps you’d like me to fill.’

Madero waited till he’d got the folder firmly in his grip before thanking the man profusely but refusing his kind offer on the grounds that he was already engaged in Illthwaite, which if a bed-and-breakfast booking could be called an engagement was true.

Back in his car, he rejoined the tidal bore of traffic, intending to retrace his approach to the town and take the road which Sam Flood had followed some hours earlier around the southern edge of the county, but somehow he found himself swept away towards somewhere called Windermere. He stopped at a roadside inn, brought up a map of Cumbria on his laptop and saw he could get across to the west just as easily this way. Feeling hungry, he entered the pub and ordered a pint of shandy (England’s main contribution to alcoholic refinement, according to his father) and a jumbo haddock. As he waited for his food, he took a long draught of his drink and opened Southwell’s folder.

Out of reach of the solicitor’s voice and with the evidence of the man’s hard work before him, he felt a pang of guilt at his sense of relief at parting company. For every sin there is a fitting penance, that’s what he’d learned at the seminary. It would serve him right if his haddock turned out stale and his chips soggy.

It had been a stroke of luck that the man he was interested in had been closely linked to one of Kendal’s foremost merchant families during the great period of the town’s importance in the field of woollen manufacture which was Southwell’s special interest.

Simeon Woollass had been the son of Will Woollass, younger brother of Edwin Woollass of Illthwaite Hall. Will’s early history (later a matter of public record in Kendal) showed him to be a wild and dissolute youth who narrowly escaped execution in 1537 after the Catholic uprising known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. His age (fifteen) and the influence of his brother won his release with a heavy fine and a stern warning.

Undeterred, Will continued to earn his reputation as the Woollass wild man till 1552 when he surprised everyone by wooing Margaret, the only child of John Millgrove, wool merchant of Kendal, and settling down to the life of an honest hardworking burgher.

In 1556 Margaret gave birth to Simeon, and once the child had survived the perils of a Tudor infancy, all looked set fair for the Kendal Woollasses. John Millgrove’s commercial acumen meant that business both domestic and export was booming, and with wealth came status. Nor did he let a little thing like religion interfere with his commercial and civil ambitions, and when Catholic Mary was succeeded by Protestant Elizabeth, he readily bowed with the prevailing wind and, like many others, straightened up from his obeisance as a strong pillar of the English Church.

Will, now firmly established as heir apparent of the Millgrove business, was happy to go along with this, which strained his relationship with his firmly recusant brother Edwin. Simeon, however, stayed close to his Illthwaite cousins and it was probably to put him out of their sphere of influence that Will sent his son, aged eighteen, down to Portsmouth to act as the firm’s continental shipping agent. He did so well that a year later when a problem arose with their Spanish agent in Cadiz, Simeon, who had a natural gift for languages, seemed the obvious person to sort it out.

Alas for a parent’s efforts to protect his child!

Simeon found life in Spain much to his taste. He liked the people and the climate, became fluent in the principal dialects, and presented good commercial arguments for extending his stay. A year passed. Will, suspecting his son had been seduced by hot sun, strong wine and dusky señoritas, and recalling his own youthful excesses, was exasperated rather than angered by Simeon’s delaying tactics. Finally however he sent a direct command, which elicited a revelation far more shocking than mere dissipation.

Simeon had been formally received into the Roman Catholic Church.

Missives flew across the Bay of Biscay, threatening from the father, pleading from the mother. In return all they got was news that progressed from bad to worse.

In 1577 Simeon had travelled north into France, ending up at the notorious English College at Douai in Flanders. In 1579 he was ordained deacon and the following year undertook a pilgrimage to Rome, whence in 1582 came the devastating news that he had joined the Jesuit Order and been ordained priest.

All this Andrew Southwell had been able to discover because of the effect it was to have on the Millgrove family’s fortunes. John had come close to achieving his great ambition of being elected chief burgess of the town when the smallpox carried him off. It was, however, generally confided that Will Woollass, now head of the firm, would eventually achieve that high civic dignity his father-in-law had aspired to.