По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

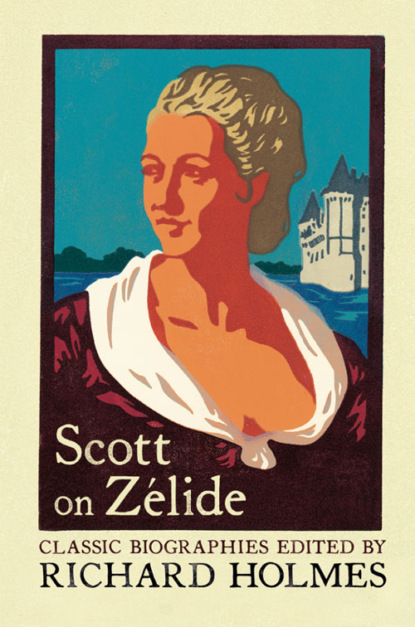

Scott on Zélide: Portrait of Zélide by Geoffrey Scott

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Scott’s attitude to Zélide herself is complex, shifting, and unexpectedly contradictory. From the outset he has pronounced her life a tragedy and a failure, yet he cannot prevent himself treating it gallantly, humorously and even at times romantically. In fact one suspects that Geoffrey Scott is always in two minds about Zélide, and part of him is always in love with her. The most beautiful and memorable images in the book are always dedicated to her. ‘So Zélide lay, lost to the world, like a bright pebble on the floor of the Lake of Neufchâtel.’

It is true that he ignores or distorts several elements in her story. He underplays the significance of her published writing (apart from its autobiographical aspect), and fails to see the importance of the later work for the feminist canon, notably the brilliantly plotted moral fable, Three Women. It is difficult to imagine that Zélide was the author of twelve short novels, twenty-six plays, several libretti for opera, and much harpsichord music as well. Nor does he connect her extensive output with younger English writers addressing similar themes, like Mary Wollstonecraft, Amelia Opie, or Fanny Burney. But this, perhaps, is a failure of historical rather than biographical perspective.

More problematically, Scott does not seem to sympathize – or should one say empathize – with what Zélide called the difficulties of having a woman’s ‘susceptible body’. He does not seem to allow sufficiently for the devastating effect of her physical inability to have children with M de Charrière, or relate this to her clandestine affair with the handsome (but still unknown) young man in Geneva sometime in 1784–5. Zélide was then in her mid-forties, feeling life slipping away, and was perhaps making her one, last serious attempt to act like Ninon de Lenclos. As Benjamin Constant pointed out, this adulterous episode, perhaps Zélide’s only real adulterous episode, produced her masterpiece, Caliste.

Above all perhaps, Geoffrey Scott undervalues the happiness that her last circle of young women friends and protegées brought her after 1790, when she was fifty. They included the flirtatious and incorrigibly pregnant maid Henriette Monarchon; the handsome and talented Henriette l’Hardy (who became her literary executor); the dazzlingly beautiful Isabelle de Gélieu; the clever sophisticated Caroline de Sandoz-Rollin; and the ‘wild, gorgeous, defiant’ sixteen-year-old Suzette du Pasquier.

These produced Zélide’s own kind of salon des dames at Colombier, and exchanges of letters, poems, and confidences quite as full as her masculine ones. Such a circle was, after all, part of Zélide’s original plan to consecrate her life to friendship as well as love. And who is to say that some of these young women, with their new independent ways, did not bring Zélide love as well as friendship?

8

For all these limitations of sympathy and perspective, Geoffrey Scott’s biography remains a subtle triumph, and a considerable landmark. It changed forever the way English biographers wrote (or simply failed to write) about women. It recognised that women’s lives had different shapes from men’s, different emotional patterns of achievement and failure. It stressed the value of a psychological portrait of Zélide, over a mere chronology, but never descended to (the then fashionable) Freudian reductionism. It suggested that from a woman’s perspective, the very idea of ‘destiny’ was different. Zélide was both subject to men’s careers within the existing frame of eighteenth-century conventions, and yet always, stubbornly and subversively, independent of them.

The biography was a deserved success when finally published in 1925. It was widely praised by the reviewers, the TLS remarking that it was ‘a biography as acute, brilliant and witty as any that has appeared in recent years.’ Edmund Gosse in the Sunday Times added Scott to the group of ‘three or four young writers’ (including Strachey) who had put to flight the ‘wallowing monsters’ of Victorian biography, through ‘delicacy of irony, moderation of range, refinement and reserve’. The book won the James Tate Black Memorial Prize, and ran to three editions in the next five years. Scott himself had the odd experience of appearing in the Vogue Hall of Fame for 1925.

Not surprisingly, there were different reactions from within his own literary circle. Mary Berenson and Edith Wharton loyally praised it, Edith greeting it as ‘an exquisite piece of work’. But Vita Sackville-West, perhaps inspired by her new passion for Virginia Woolf, felt it was too flippant, too flashy and not sympathetic enough to Zélide as a woman writer. Francis Birrell, the voice of Bloomsbury, writing in The Nation gently reproached it as ‘very readable…fashionable, cosmopolitan, and a trifle over-painted’. Years later Harold Nicolson, Vita’s husband, described it with masterful ambiguity as a ‘delicate biography’.

Nonetheless it remains a memorable prologue to the full opening up of women’s biography in the twentieth-century. It is an early attempt to recover the importance of the woman writer’s role in the culture of Europe, and particularly in the long and rich tradition of Dutch humanism. The early writings of Zélide represent a vivid response to Voltaire, and his contes philoso-phiques. While the emotional confrontation between Zélide (or rather Madame de Charrière) and Madame de Staël, and the consequent battle for Benjamin Constant’s soul, is brilliantly deployed by Scott to sum up the intellectual confrontation between Enlightenment and Romantic values.

Raymond Mortimer saw this as one of the most original features of the biography, the picture of ‘a conflict between two centuries, two states of mind, almost one might say, two civilizations’. He also added shrewdly: ‘[Scott] is a little in love with Madame de Charrière, and so are you, before the book is done.’

Many of these judgements have proved remarkable perceptive. It is now becoming clear that Geoffrey Scott’s work forms part of the 1920’s revolution in British biography, championing a briefer, more stylish and inventive form. It needs to be set beside Strachey’s Queen Victoria (1921), André Maurois’s Ariel, ou La Vie de Shelley (1925), and Harold Nicolson’s Some People (1927).

Scott himself put his claim modestly, but very well, in the note appended to the end of the book. He first makes full acknowledgement to the faithful scholarship of Philippe Godet, and then adds: ‘All I have here done is to catch an image of her in a single light, and to make from a single angle the best drawing I can of Zélide, as I believe her to have been. I have sought to give her the reality of fiction; but my material is fact.’

9

Geoffrey Scott himself was always haunted by Zélide, though in many ways she set him free. With the success of his biography, he was for the first time offered professional literary work, as the editor of the recently discovered Boswell Papers from Malahide. This brought him a new self-confidence, a proper salary, a degree of emotional independence, and a fresh start in America where the unsorted Boswell archive had been shipped. Edith Wharton thoroughly approved of this new literary adventure.

As if to appease the shade of Zélide, Scott made his peace with Mary Berenson. He ceased to trail after Nicky Mariano or Vita, and amicably divorced Lady Sybil (who married Percy Lubbock the next year). Sybil, in turn, published her translations of Four Tales by Zélide, including ‘Le Noble’ and Caliste, in 1925, the first time they had ever appeared in English. Her daughter Iris Origo, a distinguished biographer in her own right, later wrote with great kindness and perception of her wayward stepfather.

But perhaps Zélide’s shade remained a little jealous of Geoffrey Scott. In 1928 he found a new love in America. Muriel Draper, an artist living at East 40th Street, worked for the New Yorker. With her, he felt he was at last escaping his own entanglements in the past, and the world of Zélide. By contrast Muriel made New York appear ‘the most beautiful city in the world in a curious thrilling way: because it is all happening under my own personal eyes, and not an elegant dream of the past.’

He too now planned for the future. His editing project was going well, and in spring 1929 he signed a contract with Harcourt Brace for a major new biography of Boswell. Then Geoffrey Scott unexpectedly caught pneumonia, and tragically died in a New York public hospital in August 1929, aged forty-six.

The Times obituarist noted: ‘he was the perfect person to pass an evening with, the product of a high civilization…both critical and affectionate.’ One cannot help feeling that Zélide would have said something similar. Just fifty-five years later, in 1984, her Complete Works were republished in ten volumes.

The editor would like to acknowledge the pioneering work of Richard M. Dunn on Geoffrey Scott’s family papers. See Further Reading.

SELECT CHRONOLOGY (#ulink_7251eb9a-8108-531e-be52-13dda846388e)

1740 (20 October) Isabelle de Tuyll (Zélide) born at Castle Zuylen, Utrecht, Netherlands

1760 Isabelle begins secret correspondence with the Chevalier d’Hermenches

1762 Isabelle (as Zélide) publishes her first story ‘Le Noble’

1763 Isabelle meets James Boswell

1764 Isabelle writes her ‘Portrait of Zélide’

1771 (February) Isabelle marries Monsieur de Charrière They move to Le Pontet, Colombier, Switzerland

1776 Isabelle’s father dies, and her correspondence with the Chevalier d’Hermenches ends

1784 Isabelle publishes the Letters of Mistress Henley

1785 The Chevalier d’Hermenches dies

1787 Isabelle meets Benjamin Constant in Paris

1788 Isabelle publishes Caliste

1795 Isabelle publishes Three Women

1805 (27 December) Isabelle dies at Le Pontet, Colombier

1816 Benjamin Constant publishes Adolphe

1830 Benjamin Constant dies

1884 (11 June) Geoffrey Scott born in Hampstead, London

1906 Scott meets his mentor Mary Berenson in Florence Philippe Godet publishes Madame de Charrière et Ses Amis

1913 Scott falls in love with Nicky Mariano in Florence

1918 Scott marries Lady Sybil Cutting in Florence

1919 Scott discovers the works of Isabelle de Charrière (Zélide) in Lausanne University Library

1920 Scott writes to Mary Berenson and Nicky Mariano that he intends to write Zélide’s biography

1923 Scott falls in love with Vita Sackville-West, who encourages him to finish the biography

1925 Scott publishes The Portrait of Zélide

1927 Scott leaves for America, to work on the Boswell archive

1929 (14 August) Scott dies in the Rockefeller Institute Hospital, New York

THE PORTRAIT OF ZÉLIDE (#ulink_e5ed01ca-819e-5ae8-84f8-393e9f18686c)

ONE (#ulink_fcb43fab-cc77-52db-811c-4d7830b01a8d)

La Tour has painted Madame de Charrière: a face too florid for beauty, a portrait of wit and wilfulness where the mind and senses are disconcertingly alert; a temperament impulsive, vital, alarming; an arrowy spirit, quick, amusing, amused.

Houdon has left of her a bust in his fine manner: a distinguished head, a little sceptical and aloof.