По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

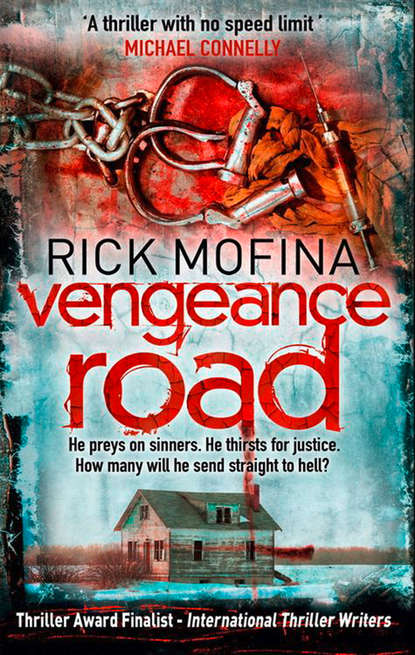

Vengeance Road

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Who?”

Catherine stood.

“Please, you can’t print anything. You have to go.”

“Wait, who told you not to say anything?”

Several moments passed.

“At least tell me who told you not to speak to the press about your daughter’s murder.”

She looked at him long and hard.

“The police.”

5

Two days after her corpse had been identified, Bernice Hogan’s shy smile haunted Gannon from the Sentinel’s front page.

Her picture ran under the headline:

Murder of a brokenhearted woman

Nursing student’s tragic path

Here was a troubled young woman whose life held promise. A woman who, despite the cruelty she’d endured, had been striving to devote herself to comforting others. His compassionate profile was longer than his earlier news stories and contained information unknown to most people, including his competition.

Not bad, he thought, sitting at his desk, rereading his feature in that morning’s print and online editions.

Tim Derrick swung by, drinking coffee from a mug bearing the paper’s logo.

“Nate likes what you did,” Derrick indicated the corner office of Nate Fowler, the paper’s managing editor, the man who controlled the lives of seventy-five people in editorial. Invoking his name gave currency to any instructions as quickly as it made people uneasy.

Fowler was not a journalist. He was a Machiavellian bureaucrat and Gannon did not mesh with him as well as he did with the other editors.

“Did he say anything else?” Gannon asked.

“He wants you to stay exclusively on the murder story, do whatever you can to make sure we own it. He said we need hits like this to boost circulation and stay alive.” Derrick pointed his finger gunlike at Gannon’s old Pulitzer-nominated clips and winked. “And if anyone’s going to take it to the end zone, it’s you.”

Gannon was not so optimistic.

He needed a strong follow-up today but faced a problem.

The New York State Police led the Hogan investigation and he didn’t know the lead detectives. He looked at their names on the last news release, Investigators Michael Brent and Roxanne Esko.

He’d put in calls to them but none were returned. He could go around them, but it meant asking sources to go out on a limb by leaking information to him.

He had sources everywhere: the Buffalo homicide squad, Erie County, Amherst, Cheektowaga, the FBI, Customs and Border Protection, the DEA, the U.S. Marshals Service, pretty much every agency in the region.

But nobody was saying much.

Maybe it went back to what Catherine Field had said about the police telling her not to speak to the press. At first he hadn’t been concerned because detectives often asked relatives of victims not to speak to reporters, especially during the early days of an investigation.

But now, as he sat at his computer searching for a new angle, he wondered if it was a factor here. He couldn’t shake the feeling he was missing something.

“That Hogan case is sealed, man,” one source had told him. “But I heard that some of the people close to it were rattled by what the guy had done to her. I heard that it pushes the limits of comprehension.”

Another source said that a number of law enforcement agencies were called in to help, possibly because of the area where she was found, and possibly because of other complications.

“I’ll tell you something nobody in the press knows,” the source said. “There’s a closed-door case-status meeting with a lot of cops from a lot of jurisdictions. It’s been going on all morning out at Clarence Barracks.”

Gannon grabbed his jacket.

He’d go out there and see if anyone would talk to him.

The New York State Police patrol east and northeast Erie County from the drowsy suburb of Clarence, east of Buffalo. Clarence Barracks was on Main Street, housed in a plain one-story building.

When Gannon arrived, the woman at the reception desk was twirling her pen and talking on the phone.

“I’ve been temping all week, just when they get this big case … meeting after meeting, people coming, people going—one second, Charlene.” She clamped her hand over the phone. “May I help you?”

“I’d like to see Michael Brent or Roxanne Esko. I’m with the Buffalo—“

“They’re all in the meeting, third door on the right.” She pointed down the hall with her pen. “I’m supposed to send everybody there.” She went back to her conversation. “What’s that? She’s pregnant! OH MY GOD! How many is that now?”

“But I’m with the Buffalo Sentinel.”

Ignoring what he’d said, the receptionist pointed him down the hall.

“Go,” she told Gannon. “It’s all right. Everybody’s in the meeting.”

He hesitated for as long as it took the receptionist to buzz him through the security door. As he went down the hall he could almost hear the floor cracking under him for he was treading on thin ethical ice. Through innocent circumstance he’d gained entrance to the inner sanctum of the investigation of Bernice Hogan’s murder. The door to the meeting was half-open. He could hear loud voices.

How should he play this?

He’d knock on the door, identify himself then request to speak to Brent or Esko. They’d likely shoo him away, have him wait at reception.

At that instant the door opened and a man he didn’t recognize exited, talking on his cell phone. Gannon turned and bent over a water fountain as the man, his tie loosened, shirtsleeves rolled up, whisked by him to the opposite end of the hall talking loudly on his cell.

“Tell Walt this Hogan thing is going to be a ballbuster,” he said into the phone. “No one will believe where they’re going with it. Yeah, they’re keeping a tight lid on this. Yeah, I got to get back.”

The man returned to the room and Gannon inched closer to the door.

It remained partially opened. Voices of people arguing spilled from it.

“I don’t buy it.”

“Look at what we know so far.”