По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

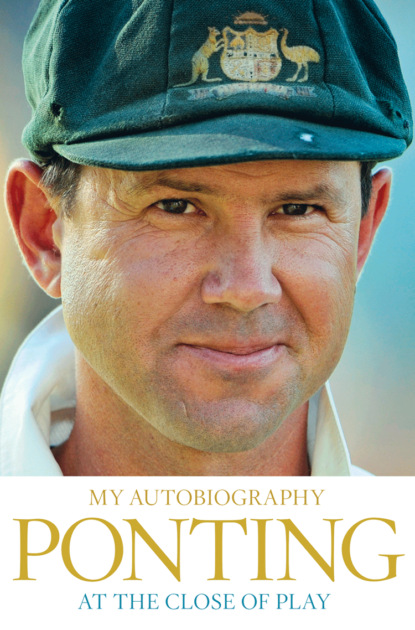

At the Close of Play

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Being born in a small town had its advantages as everything was close and parents never needed to worry too much about where the kids were. If I was missing Mum or Dad just had to find the nearest game of cricket or footy and they were comfortable that even if I was in the sheds with the older blokes that they were all neighbours and friends and they were all keeping an eye on me. I had a BMX bike that I used to ride about town, and often to senior cricket matches involving the Mowbray club, my home team, Dad’s old team, a club that in the years after it was formed in the 1920s used to get many of its players from the nearby railway workshops or the Launceston wharves. I started following them partly because I just loved the game, but also because my Uncle Greg was one of their best players.

Cricket fans know him as Greg Campbell. He’s Mum’s brother, 10 years older than me and a man who had a significant influence on my cricket career. Greg encouraged me all the way and spent a lot of time playing cricket with me, but more importantly he set an example. Looking back now I can see how important it was to know that someone from our family could make the big time, could go all the way from Launceston to Leeds, where he made his Test debut in the first Test against England in 1989. That was a huge day in our lives. Not only was Mum’s brother bowling for Australia, another local hero, David Boon, was playing too. Our little town provided two Test players. It was like Launceston had colonised the moon, although in my world landing in the Australian cricket team was a bigger deal.

Having someone in the family who could do that made the dream of one day doing it myself all the more real. Here was a bloke in the side who had played cricket with me in the back garden. It meant Test cricket was a viable option for people like us. Greg nurtured my interest in cricket and we could get pretty competitive when we played each other. One day, when he thought I was out and I thought I wasn’t, we had to go and ask Dad to come out and decide. The ruling went in Greg’s favour, which didn’t surprise me because he and Dad were best mates, to the point that when Dad coached the footy team at Exeter (a town 20 kilometres north of Launceston) one year, Greg went there and played as well. If there was one thing that could and still does get the men of our family into an argument it’s sport. You should hear Dad and myself when a golf game is on the line. To an outsider these disputes might sound pretty serious. They’re definitely earnest, but it’s just our competitive nature and I suppose it was something that got me into hot water a few times over the years.

One of my strongest memories involving Greg is the day when Mum told me that his Ashes kit had arrived. I flew around on my bike to his house in Invermay to check it all out, to try on his baggy green cap and even his Australian blazer, which was many sizes too big but felt absolutely perfect. He was a hero of mine then and he remains a hero of mine today; he’s a good friend who helped show me the way. Standing in that Launceston house dressed in his gear I knew there was only one way my life was going.

In the early and mid 1980s, when I started watching Greg and his team-mates at the Mowbray Eagles, they played their home games at the ground at Brooks High, the local high school at Rocherlea. Sometimes I’d be down there at nine in the morning, even though the game didn’t start until 11. I just didn’t want to miss anything. It was the same when I joined the team working the scoreboard at the Northern Tasmanian Cricket Association (NTCA) ground during Sheffield Shield games — I scored that gig after I rode my bike down to the ground, found the right person and asked for the job. They paid me $20 a day, but much more important than that, I had a bird’s eye view of the game, the warm-ups, the net sessions, everything.

As I said earlier I loved to sit in the corner of the Mowbray A-Grade team’s dressing room. Some of the tactical talks and most of the jokes went over my head, but at the same time I was absorbing plenty. I saw their loyalty and passion for each other and the game. Not least, I saw how those men played hard and fair, enjoyed the wins and hated the losses, wouldn’t take crap from anyone and always sought to be friendly with the opposition once the game was done. Most times, that mateship was reciprocated and if it wasn’t, we knew who the losers were. Those were lessons in cricket etiquette for me. The men set the standard and they said ‘no matter what happens on the field you shake hands and you have a beer after the game’. It was a tradition in Australian Test cricket but one that all nations were keen on. Once it happened after every day’s play, then it shifted to the end of the Test and later, because everything was so hectic, it became something that you did at the end of a tour. I know whenever we had a drink with the opposition after a series it was a positive experience. Arguments happened on the field and stayed there, relationships were built off it.

If Uncle Greg was my favourite, everyone else in the Mowbray dressing room was a star, too. I’d seen his fast-bowling partners, Troy Cooley and Roger Brown, bowling in the Sheffield Shield. Brad Jones, later my coach when I played for the Mowbray Under-13s, had played for Tasmania Colts. Richard Soule was the Tassie wicketkeeper. A standout was Mick Sellers, a strong burly left-hander who strode out to bat at the start of an innings and whacked the ball all over the place. He used a big Stuart Surridge Jumbo, four or five grips on the handle, batted in a cap and took on the fast bowlers every time. If there was ever a blueprint made of the classic Mowbray Cricket Club player it was Mick. He represented Tasmania in a few first-class and one-day games in the 1970s. He played over 400 games for Mowbray and was the club coach. After he retired, he would still be down at the ground, helping to roll the wicket, put on the covers, anything to help. He remains a legendary figure around the club. He was there, of course, when I came back at the end of my career.

He looked after me in those days when I was a constant in their dressing room. He got me involved when the time was right, and sheltered me at other times. In doing so, he taught me so much. They all did. They were kind and generous men. At the same time, everyone feared playing Mowbray; I could see that from the looks on the opposition’s faces, what they said to each other while we were fielding. A game against Mowbray was a tough day at the office, plenty of words spoken, no quarter given. A lot of what you see in me today is a result of learning the game the way they used to play it. When we were truly at our best other sides hated playing Australia. South African cricket captain Graeme Smith admitted as much once, and while a lot of people took this the wrong way, to me and to the others in the side the point was we would not give an inch on the field.

After stumps, if Dad had come from golf to see how the boys had played, he would put down his beer, and bowl to me so I could try to mimic the shots I’d seen played earlier in the day. At home games, we used a big incinerator drum as the wicket and just the same as when they were bowling to me at school my ambition was to never get bowled. Dad was my first coach, at cricket and footy, and he could be a tough marker, but he wanted me to be a winner and I wouldn’t have wanted it any other way.

You often read or hear of the so-called bravery of sportspeople who overcome great adversity to win. I’ve certainly seen and been a part of some very brave sporting accomplishments over the years, but I must say that the use of the expression ‘bravery’ is completely over-stated when you are witness to some real acts of bravery in everyday life. Rianna and I have met some of the bravest children and families in our work around the area of childhood cancer. The children, especially, move us. While they fight the most horrible disease in the world, they show incredible resilience to go through their treatment and hopefully survive. Without a doubt, it’s even tougher for the families. Parents and grandparents continually ask the question: ‘Why our child or grandchild?’ They have to be brave for the child while maintaining a sense of normality to support siblings and other loved ones at a time that most of us cannot even start to imagine how difficult it must be. Some of the bravest families we have met had children who didn’t survive the battle with cancer.

In our days of supporting the Children’s Cancer Institute Australia, I stayed in regular contact with a number of children, exchanging text messages and keeping up to date with their progress. Those close to me know that I’m a bit slack at returning text messages but my contact with these children was different — I always made a point of answering straight away. Sadly, in many situations, a message would come through from parents letting me know their child didn’t make it. Over the years, though, we have stayed in contact with many families whose children have survived. One very special child close to our hearts is Toby Plate from Adelaide. I first met Toby and his family on the eve of the Adelaide Ashes Test in 2010. During that series, I had a young cancer sufferer join me at each of the opening ceremonies. Of all the children I met that summer, Toby was the sickest — fighting a brain tumour and undergoing the most intensive treatment. We spent considerable time together that day and he left a lasting impression on me. The next day we stood together and sang the national anthem before the second Test began. Sadly not all the children who stood with me in the anthem ceremonies that summer survived their battle with cancer, but Toby did. We have stayed in touch and last year played cricket together at the MCG with Owen Bowditch, who was with me at the Boxing Day Test opening ceremony that summer. These boys and their families epitomise bravery for me. They are symbolic of what it means to overcome adversity. Not all the stories have a happy ending but the bravery shown by each and every child that is confronted by cancer is overwhelming, to say the least.

(#ulink_212fe861-5e78-53b1-b416-764a3ddf9cc2)

MOST KIDS PLAY CRICKET with their fathers in the backyard, but where we came from there was a bit of a tradition of the fathers dropping down in the grades to guide their sons through. We never had a big partnership, but I loved the year I played with my old man.

Dad retired from weekend cricket to concentrate on his golf well before I played my first serious game, but after a number of seasons on the sidelines he was talked into making a comeback, the lure being the chance to play with his son. Up until this time I had played a little at school and some indoor cricket, but all the while I was waiting to join the men and that’s what I did on the eve of my 13th birthday.

We were both in the thirds at the start of the 1987–88 season. Dad was captain, I was a tiny but promising novice who struggled to hit the ball off the square. My technique was pretty good, but lofted shots were risky because I was never sure I could get the ball over the fielders’ heads and there was just not enough power in my arms to play a forcing shot through the field. Still, Dad put me up near the top of the order, reasoning the experience would be good for me, and eventually the day came when he walked out proudly to bat with me at the other end. It was a home game against South Launceston. Just like my favourite players — Launceston’s own David Boon, former Australian captain Kim Hughes and the then Aussie skipper Allan Border — did in the Test matches I watched so avidly on television, I sauntered down the pitch before Dad faced a ball, to tell him the leg-spinner who was bowling, a bloke named Matthew Dillon, was getting a bit of turn.

‘Just be careful for a little while,’ I suggested. I was all of 12 years old. ‘Don’t play across the line because he’s getting a bit of turn.’

The first delivery was handled without a problem, but the second ball Dad went for the big shot and skied a simple catch to cover. I was really disappointed and a bit dirty that he’d thrown his wicket away, but thinking about it now, I guess this might have been the first time I saw what pressure can do on a cricket field — we’d talked so much about what it would be like to bat together, how we really wanted to have a decent partnership, and that seemed to be what Dad was thinking about rather than just playing each ball on its merits. At least that’s what we decided at the inquisition after stumps and it says something about the way we were that we sat down and analysed what went wrong. Ironically, in the matches that followed, it was me, not Dad, who struggled to make a big score. At season’s end, he was top of the competition for batting aggregates and averages, and having guided me through my first year, he promptly retired for good so he could get back to playing golf all weekend.

I think part of his motivation to come back was simply to protect me, because he knew what senior grade cricket in Launceston could be like. I was sledged more in my first season with Mowbray than I would ever be sledged again in my life. I’d developed a bit of a reputation as a ‘young gun’ and some old blokes seemed very keen to put me in my place. There were a number of guys playing third grade who were in a similar boat to Dad — older, former top-grade players who were now helping young guys out and at the same time were eager to ‘educate’ teenage opponents who stood out. Old bulls out to slow the young bulls down and teach them a thing or two about how the game should be played. It was a time-honoured tradition and one that we might have got away from a little now in the select streams of Australian cricket where the best young players are channelled off into age competitions or lured by scholarships to private schools where they only get to play against people their own age.

You can get put back in your place fairly quickly playing against cranky old blokes who played their first game before you were born. Respect is earned in these scenarios and if you have the talent and character to survive you come out a better cricketer and a better person. I got fearsome sledgings on a few occasions; one that stands out was the wicketkeeper from Riverside who had played some representative cricket a few years earlier and now gave me an almighty serve on their home ground after I made the mistake of responding to something he’d muttered from behind the stumps. If I’d been out of line, Dad would have said so. Instead, he got into this keeper and the language was pretty full-on.

Most weeks someone tried to knock my head off, but nothing about playing with the men harmed me. Some people keep their kids away from real cricket balls and some talent streams lock them into playing in their age groups for fear they will be roughed up and mentally scarred. Fortunately I had no fear and came through unscathed. Indeed, the value of playing against cricketers twice, even three times, my age shone through in the January of that season, when I played for Mowbray in the Northern Under-13 Cricket Week — I scored four separate hundreds in the space of five days, all of them undefeated. To me the other team were just like Drew and there was no way they were going to get me out. It was a simple game in those years — you were either in or out and it was obvious who you were competing with; with age comes the doubts and mental struggles that all sportsmen face.

Apparently at one point during this tournament a few of the parents became a little agitated because their kids weren’t getting a bat, so Dad suggested to our coach, Brad Jones, that he give someone else a go. Brad disagreed, saying he’d sort it out later. ‘I didn’t think it warranted this kid who loved the game so much being denied the chance of batting just because some parents wanted to watch their kid bat,’ he recalled when interviewed a couple of years back.

Two weeks later, I was picked in Mowbray’s team for the final game in the Northern Under-16 Cricket Week and made another ton, which was enough for me to be selected in the NTCA’s Under-16s training squad and the Tasmanian Institute of Sport Under-19 squad, and for me to get my picture in the paper for the first time, alongside an article that was headlined: ‘Ricky’s Making a Big Hit in Cricket Circles’.

From that time on, I never really thought about a working career outside of sport. When people asked me what I was going to do for a living, I’d reply, ‘Play cricket.’ I think they thought I was joking, but I was very serious.

I was a student at Brooks High School, Rocherlea, by this stage, and one day at school I was interviewed by journalist Nigel Bailey. Today, the story is stuck in Mum’s scrapbook and my responses are exactly what you’d expect from a 13-year-old grade-eight student terrified of embarrassing himself. When asked if I’d like to play for Australia, I replied, ‘I’d love to play for Australia.’ When Nigel asked me if David Boon was a hero, I responded, ‘I look up to David Boon because he’s from here.’ And that was about it, except when I was asked what I liked to do outside of cricket.

‘I like to fish for trout with my dad,’ I said.

THE FIRST TIME I threw a line in the water occurred during school holidays at Musselroe Bay, a village on Tasmania’s far north-east coast, where my grandparents had a caravan and we’d stay at one of the campsites. Quite often, Dad’s sister and her kids used to come up as well and other relatives of Dad’s had a shack a couple of minutes down the road, so family gatherings could be huge. You had to drive through old Ponting country to get there, the road running through the town of Pioneer which always had Dad telling stories as we drove.

Getting there was half the fun. Dad had a few cars when we were young and none of them were very flash. There was an old Holden, a Ford Cortina and a Toyota Cressida he bought when he got laid off from the railways. My grandparents had a station wagon and would take most of our gear in the back of that. We’d squash into the family car and hold our breath most of the way, just hoping it would get us there.

In Musselroe I’d watch the Boxing Day Tests on a little black-and-white portable TV, sitting on a couch or lying on the floor. I can remember Dennis Lillee bowling off his long run, Allan Border wearing down the opposition and Kim Hughes playing a brand of cricket that I hoped to emulate one day. At other times we’d go out on Pop’s little dinghy fishing for salmon. My childhood memories are of us never failing to bring back at least enough food for dinner that night. These were the happiest days of my childhood.

If we weren’t fishing, opening Christmas presents or watching Test matches at Musselroe Bay, the odds were I was involved in a sporting activity of some kind. A couple named Sue and Darrel Filgate had a shack on a large, well-grassed block of land, and it was nothing for me to play cricket all day in summer with the Filgates’ two sons, Darren and Scott, who were around the same age as me. There were days when I’d bounce out of bed in the morning, have a slice of Vegemite toast for breakfast, and then be gone for the day. Often, one or more of Mum, Dad, Nan or Pop had to come up to the Filgates’ house to get me for dinner, because I had no sense of time when we were on holidays, especially if I was batting.

I thought I was going okay and Nan obviously agreed with me. Around the time of my 10th birthday, it could have been Christmas 1984, she gave me a T-shirt that featured an ambitious message: ‘Inside this shirt is a future Test cricketer’. A few people had a friendly go at me whenever they saw that shirt, whether it was that Christmas or in the next few that followed. To tell you the truth, I couldn’t see a problem.

UNTIL I WAS 13, most of the organised cricket I played was at school or indoors. Wherever I played I made sure bowlers worked hard if they were ever going to be rid of me. Drew wasn’t the only one who suffered. I don’t think I was dismissed in my two years of cricket at Mowbray Heights Primary and I do recall that in grade six they introduced a limit on how long anyone could bat — if a batsman reached 30, he had to retire — to stop me from batting all the time.

Our coach was also the umpire and the scorer too, so whenever I was at the bowler’s end I’d ask him, ‘How many am I?’ My plan was to get to 29 and then aim for the boundary so I’d finish unconquered on 33 or 35. The indoor games were played at the Waverley Area Cricket Arena, at St Leonards in south-east Launceston, known across town as the WACA. I was our team’s wicketkeeper. Dad was captain.

I played a lot of indoor cricket, including some big games in Hobart representing the WACA. I loved it, but my old man wasn’t so keen on me playing so much because he thought it was bad for my outdoor cricket. The key to indoor cricket is to push the ball into the side netting, which meant we were always hitting across the line. ‘You can’t play straight in indoor cricket,’ he’d sneer, because a drive back to the bowler could lead to a run out if the batsman at the non-striker’s end (who was always looking for a quick single) backed up too far. He was right, of course, and eventually I gave the game away for that reason.

THE FIRST ‘SERIOUS’ BAT I ever owned was a Duncan Fearnley size five that Dad bought for me from a local sports store. Then, one day not long after my 10th birthday, Dad and I went along to watch the Mowbray Under-13 team in action. Within minutes of arriving, we learned they were one player short, because someone had dropped out at the last minute. It was my big chance and not one I hadn’t fantasised about. The people at the club were aware I was keen and they knew I could hold a bat and catch and throw, and as there was no one else available, I was drafted in, batting last and with no chance of getting a bowl. I was the most excited kid in the world.

In our first innings I made one not out, but we were soundly beaten and the other team sent us back in, even though there was little chance of an outright result. I had the pads on and the coach said I could go in again if I wanted to, an invitation I wasn’t going to knock back. While I was waiting for the umpires to take us out Dad came over and said quietly, ‘If you can get to 20, I’ll buy you a new cricket bat.’

Years later, this was the knock Dad recalled when he was asked if there was a moment when he realised I was going to be a good batsman. I wasn’t much taller than the stumps but I knew how to play straight and I could leg glance and push the ball between the fieldsmen at mid-wicket and mid-on for a single. I certainly wasn’t scared. In the end, it was more a matter of whether I’d get to 20 before sunset, but I made it and by the following Saturday I had my Gray-Nicolls ‘Super Scoop’, a David Hookes signature. A year later, I was given some County gear — a bat, gloves and pads after impressing the right people at indoor cricket — but the Scoop remained my favourite bat until, in early 1988, on the back of those hundreds in the Under-13 and Under-16 Cricket Weeks, I was signed up by Kookaburra, whom I’ve been with ever since.

This sponsorship deal was instigated by a gentleman named Ian Young, a man who became a family friend. Youngy was the hardest working bloke I’ve ever met, someone who was passionate about everything he did. I first ran into him when I got the part-time job as a scoreboard attendant at the NTCA ground, where he was the curator, but he really came into my life early in my first season playing for Mowbray. One night when we were using the indoor nets at the NTCA ground, he stopped to watch me bat and then came up to me afterwards and offered to help me out.

Youngy had already devoted a lifetime’s worth of work to the game, as a player, mentor and administrator, and now here he was — clad in his King Gee work pants, steel-capped boots and big flannelette shirt — meeting me at Invermay Park on Saturday mornings after he’d worked on his pitches in the early hours, to bowl at me for over after over, all because he believed I was a good cricketer in the making. Not long after, he was appointed coach at Mowbray and our bond grew tighter. If he ever rang and said, ‘Let’s go have a hit,’ I’d be on my way. I’d bat, he’d bowl; as I remember my childhood, he was always around to throw balls at me or bowl to me. But he never forced me to go to practice; in those days, I would have batted all day every day if I could have. As long as I worked hard, greeted him with a firm handshake and looked him straight in the eye and listened when he spoke to me — that was all he wanted. When it came to batting technique, he was big on the simple stuff: play as straight as you can and wait for the ball. For me, the biggest buzz was simply that someone of his stature was taking such an interest in me; that he cared as much as Mum and Dad did.

Youngy always stood out in the crowd, and not just because he was a tall bloke. He was confident, assertive, never short of a word but always talking sense. It was so good to have him on my side. He was a coach who, if he saw a problem, he tried to fix it and he was happy to work and work until things were right. He taught me the value of a good work ethic. He’d been an outstanding bowler in his day, and if I made a mistake in the nets on a cover drive, you could guarantee the next ball he’d bowl would pitch in the same spot, to give me the chance to do it better.

Sometimes when he got tired Youngy would invite me back to the indoor nets, where he would feed one of the bowling machines so I could keep working on my technique. Often, we were joined by his youngest son Shaun, who was four-and-a-half years older than me and played his cricket with South Launceston. Two other sons, Claye and Brent, were also excellent cricketers. Claye even opened the bowling for Tasmania one season with Dennis Lillee. Shaun, a gifted all-rounder, and I would play plenty of Shield cricket together and in an Ashes Test at the Oval in 1997, an event that prompted the Launceston Examiner to organise a photo of two proud fathers, Ian and Graeme, which they put on the front page of the paper.

In 1988, Youngy was good mates with a bloke named Ian Simpson who was working for Kookaburra at that time, and he told him, ‘There’s a kid down here who looks like he might be all right.’ I was introduced to Ian soon after, when he was in Tassie for the Kookaburra Cup final and about a week later, a kit, complete with bat, gloves and pads, landed on our front door.

As the story goes, Ian Simpson went back to Melbourne and told Rob Elliot, the boss at Kookaburra, ‘We’ve got this kid down in Tassie we’ve got to look after. I’ve sent him some gear already.’ Rob, who is a terrific bloke but who can be tough to deal with, snarled back, ‘Why don’t you go back to the local prep school and find a few more kids. We’ll sign ’em all up!’

I’d like to think the deal I signed turned out to be a pretty good one for Kookaburra, but Ian Simpson left the company soon after, and within a few weeks he was actually mowing the lawns at the Kookaburra warehouse. Not that he was bitter about this development — his first venture after leaving the cricket-gear business was to take on a ‘Jim’s Mowing’ franchise, which worked out very well for him. One of his clients was Kookaburra and no one greeted him more warmly, if they crossed paths, than Rob Elliot.

I obviously made a good impression in those days. Around that time Tasmanian ABC cricket commentator Neville Oliver told a reporter from the Examiner newspaper: ‘We’ve got a 14-year-old who’s better than Boon — but don’t write anything about him yet, it’s too much pressure.’

Back then, I continued working with Ian Young and our bond remained as strong as ever until he passed away, aged 68, in October 2010. He was always a fantastic friend and one of my strongest supporters. I was playing a Test match at Bangalore in India when Ian died and was on the flight home when he was laid to rest in Launceston. On that plane I had plenty of time to think about everything he taught me, about batting, leadership and life. Like just about everyone connected with the Mowbray club, he was big on loyalty, big on sticking with your mates and on looking after each other. And I thought about his ability to cut to the core of a problem but then help you find the correct answer for yourself, rather than just giving advice and hoping you understood. Wherever I was in the world, he would always call me if he thought he’d spotted something about my game that wasn’t quite right, and because he knew my technique so well his advice was inevitably on the money. But I was only one of a great number of promising cricketers he helped on and off the field, which is one of the reasons, in the days after he died, so many people referred to him as a ‘champion’ and a ‘legend’.

The last time I caught up with Ian Young was when we arranged to meet at a restaurant located, appropriately enough, just across the road from Invermay Park. The thing that sticks with me of that final meeting was how we greeted each other: I looked him straight in the eye and gave him a firm handshake, no differently to how we did it when I was just a little kid, all those years ago.

Missing Youngy’s funeral because of the demands of cricket was hard, but that was the nature of the job. From an early age the game took me away from the people who introduced me to it and made me the person I am. I did get used to it but I can honestly say it never got any easier, in fact as I got older it got harder but I suppose that’s just the way life goes. I know I wouldn’t have swapped my lot for anything and I know I was doing something that people like Mum, Dad, Youngy and so many others wanted for me.

Still, it would have been nice to have been there for someone who’d always been there for me.

Words can never express how grateful I am for the upbringing my family gave me. My childhood memories are always front of mind for me and are detailed in the early chapters of this book. They are special memories that have become even more important to me as I have travelled around the world.

The toughest part of leaving home and becoming a professional cricketer was the disconnect from my family back in Launceston. When I first moved away, I didn’t realise that my cricket journey would end some 23 years later when I was married with two children and settling down in a new home in Melbourne. But that’s now a reality for me and I can’t wait to re-connect with the family back in Tasmania. That might sound quite dramatic, but a recent phone call from Dad reinforced the sometimes remoteness of our relationship. ‘So I can call you again now!’ Dad said with a cheeky chirp in his voice. You see, when I was overseas, Dad would never call me on my mobile. If he or Mum needed me, they’d get Drew or Renee to text or call me and I’d phone home. But that was very unusual. I’d keep up to date with how things were at home through regular texts and infrequent calls from Drew and Renee.