По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

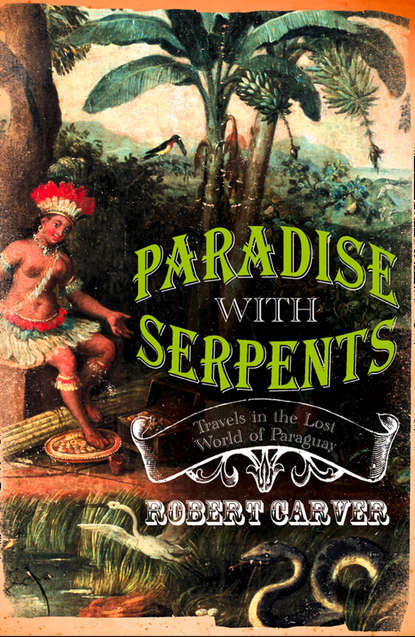

Paradise With Serpents: Travels in the Lost World of Paraguay

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Had Stroessner and Perón met?’ I asked.

‘Oh, yes – when Perón was overthrown Alfie was just starting out as a Junior-Jim dictator. He sent one of those smart, blackhulled fascist-era Italian gunboats that are moored opposite the palace down the river to BA to collect Perón, who’d taken refuge in the Paraguayan Embassy. Perón was well on his way down the usual mestizo war-against-the-world track when the air force had enough of him and bombed him out of his own palace. I think the navy were involved, too. He’d opened hostilities against the Catholic Church – like Francia did here – and was about to close the cathedral in BA and turn it into a workers’ playground. Every South American populist leader is potentially Tupac Amaru, the Inca noble who revolted against the Spanish in the 18th century. They want to bring down the house around them as they fall. Although they have absorbed all the French, Spanish and English customs, uniforms and ideologies, superficially at least, they remain spiritually Indian – that is, in revolt against the European way, while being besotted with the outward show of gringo style. It’s the latino paradox. They love us and hate us, and end up hating themselves for having absorbed so much of us. The Brazilian literary movement of the 1920s and 1930s called the antropofagos had a saying that they “ate a Frenchman for breakfast every day”. It was a reference to the Tupi-Guarani traditional cannibalism which the Europeans found so distressing when they arrived, on account of resurrection being made so complicated and difficult if people were eating each other all the time. I’ve never actually seen a direct prohibition on cannibalism in the Bible, mind you, have you? It’s kind of subsumed in the love-your-neighbour guff, I guess. There’s a strain in South American life that would like to undo the Conquest completely. It’s much the same in Africa, which South America resembles far more than most Europeans realize. Bokassa, Idi Amin and Mobutu could all have been South Americans, easily – the uniforms, the mania, the corruption, torture and confusion. The cross-cultural derangement is there, you see, on both sides of the Atlantic. King Lear with a colour chip and a culture chip, one on each shoulder.’

It was Alejandro who advised me to make a pilgrimage to see the British Ambassador. I asked him why. It seemed such a curious mission to undertake.

‘Because ambassadors have an unusually high profile in this country. Paraguay is right off the beaten track, the Gringo Trail, which you’ll have heard of, does not pass through here, as it’s too dangerous and not romantic enough, no native ruins and no McDonald’s. So few foreigners of note ever come here – de Gaulle was the first head of state ever to do so, by the way – that the foreigner is wildly overglamorized, and certain ambassadors act almost as vice-regents, deferred to by the governments which are always lacking in self-confidence and savoir-faire, not to mention credibility. In particular the ambassadors of the USA, Great Britain and France exercise great influence and add lustre to the shabby local political scene. These are countries important to Paraguay. The country was so nearly snuffed out by the War of the Triple Alliance, that Paraguayans do not trust either Argentinians or Brazilians. Good, cordial relations with these three most powerful states, who could stop any potential neighbour aggression, are very important here. You know that during the Falklands War, thousands of Paraguayans rang up the British Embassy offering to fight the Argentinians on the British side? What made it even richer was that the woman answering the Embassy switchboard was an Argentinian! ¡Ole! But seriously, if you ever found yourself in difficulties in Paraguay – and that is not hard to do at all – then knowing your Ambassador could prove very useful.’

But would the British Ambassador be in the slightest bit interested in seeing me, I queried. I couldn’t really imagine him wasting his time on such a trivial matter.

‘He’ll be delighted. You will probably be the first respectable Brit passing through for quite some time. Usually, the only ones who come here are on the run from Scotland Yard. He will be sitting twiddling his thumbs up there behind the armed compound, and you will be good for a whole morning of diplo-chitchat. He can put you in his monthly round-up to the FO – met and debriefed visiting British journalist and author Robert Carver who was en mission in Paraguay, a full and frank exchange of views ensued, etc. etc.’

I thought this was all highly unlikely, frankly, but I recognized good advice when I heard it.

‘Get the old bat on the reception desk here to ring up the Embassy and make an appointment for you. Your status will rise 500% immediately inside the hotel, for a start, and word of it will spread through Asunción, which is a small and gossipy town, in the end. You will become respectable, in a word.’

I expressed the doubt that anyone in the city would find me of the slightest interest, respectable or not.

‘Don’t be too sure of that, Don Roberto. Every foreigner who arrives here is photographed at the airport when coming through immigration – you noticed the big mirror, which was a see-through one from behind? A file is opened on everyone by the secret police, just in case – where they stay, who they meet, what they say about Paraguay. The big paranoia at the moment is Colonel Oviedo’s agents. A Brit would be a good disguise. Your profession, “journalist”, is immediately of interest to the pyragues – the hairy feet, as the spooks are called in Guarani. Your suitcases will already have been searched, and the number and type of your cameras will have been noted. The hotels always have a tame pyrague to do such elementary first moves. Although local film developing is not up to international standards it would be a good idea to get at least two or three films processed and printed up here, and leave the results around in your room when you are out and about – snapshots of the national monuments, parks, palazzi and so forth. This will show you are not saving films with compromising shots – military installations, the air force planes at the runway, say – to smuggle out and develop in UK or Brazil, as you came from Sao Paulo, and are flying back via there. Oviedo is just across the border in Foz do Iguaçu, and it could be very convenient for him to use a visiting British journalist to take a few useful snaps for him. He’d pay very well, I’m sure. You could have been recruited in London. There are certainly Oviedistas there who have already been in negotiations with the UK government as to what stance the latter might have if and when their man seizes power here. As you have at least two different cameras, I can’t help having noticed, one standard 35 mm, the other panorama, it would be a good idea to get at least one film from each developed, even if they can’t do the panorama properly here. Just to show you are not hiding anything. This is how the secret service mind works, you see, suspicions about ordinary things like cameras, which most Paraguayans don’t have and never use. Leave the cameras in your room, too, so they can be inspected. Notebooks, also. If you don’t, they may assume you have something to hide, and your cameras may be stolen, just to see what’s on the film inside. If you carry them with you all the time, this may mean you have to be attacked, possibly even killed, in order to get the films. Life is cheap here. It costs US$25 to bump someone off, I’m told – a policeman’s wages for a week – when he gets them, which isn’t often. It might also be a good idea to fax an editor in London, real or imaginary, a “colour” piece on Paraguayan wildlife, say – David Attenborough zoo quest sort of stuff – armadillos in the Chaco, pumas in the pampas, piranha in your soup, and so on. Say how much you are enjoying this peaceful, friendly country with its unspoiled, kindly people and charming, beautiful women. That is the sort of journalism they like, the pyragues, from foreigners. It will justify your existence here. Things not to mention are: 1) Oviedo and imminent, bloody coups d’état, which are called golpes in Spanish, by the way; 2) cocaine, cocaleros and drug smuggling; 3) Nazis and hidden Nazi gold; and 4) corruption and the crooked government – i.e. anything that is actually real. Keep all that until you get back to Europe. Alfie had an Interpol agent from France, a genuine Frenchman, mind you, not a local with Froggy papers, blown up inside his airplane as it was about to leave Asunción. It was on the runway, taxi-ing for take-off. Killed everyone on board, including the narco-cop, who had uncovered some embarrassing evidence of heroin smuggling among members of Alfie’s government.’

I thought privately that this was all highly fanciful, and that Alejandro was more than a shade paranoid, though I said nothing out of politeness: in fact I took his whole spiel as alarmist, of the sort those in the know love to plant in the minds of the timid newcomer. As events progressed, however, I began, slowly and reluctantly, to come round to the idea that some, if not all, of what Alejandro suggested might have a grain of truth to it. His words echoed in my mind, right up until the last moment, when sweating and frankly terrified, I sat waiting on the tarmac in a crammed exit flight, waiting to see if we were in fact going to be blown up before we took off. Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold, as W. B. Yeats sagely observed: the questions no one can answer are: a) how fast are they falling apart, and will they take me with them when they finally explode? and; b) will the centre be able to mount one last horrendous act of violence before it falls apart and bumps thousands off including oneself? An old hippy on the island of Ibiza who had hitched right round South America, including Stroessner’s Paraguay in the 1970s, had advised me laconically, ‘It’s very easy to get offed in Paraguay – paranoiaguay, as we used to call it.’ How right he turned out to be, and how little things had changed in thirty years.

Six (#ulink_f70657b1-7e7a-502c-b33e-9173bc92566b)

An Ambassador is Uncovered (#ulink_f70657b1-7e7a-502c-b33e-9173bc92566b)

Finding the British Embassy was not easy. Once, it had been downtown, lodged in an upper floor of an office building. Terrorism and attacks on British diplomats in other parts of the world had meant a whole new secure complex had been built far out in a new suburb which hardly anyone in town knew how to find. It was not even registered in the phonebook, and it was so new the large-scale map of the city in the hotel foyer wall did not include the suburb. Eventually, after contacting Gabriella d’Estigarribia, who was up on these sorts of things, the hotel receptionist did manage to phone the Embassy, find out the address, and book in an appointment for me with His Excellency, whose diary seemed as empty as mine – any day at any hour of any day would be convenient, it seemed. I spoke to the Embassy secretary myself, after all the toing and froing had been got over: she had a brisk, efficient manner and spoke excellent English, yet was not herself English. I wondered if it was the same lady who had fielded all those calls from ardent Paraguayans volunteering to take a swipe at the Argies in the Falklands War. Plucky little Paraguay had a reputation for trying to get into other people’s wars. Stroessner had volunteered to send troops to Vietnam, but Lyndon Johnson had turned him down; an unusual case of preferring someone to be outside the tent pissing in, than inside pissing out. A Paraguayan regiment or two, particularly of horseborne hussars, say, or lancers in 18th-century full-dress uniform, would have enlivened the bar scene in downtown Saigon, if nowhere else.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: