По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

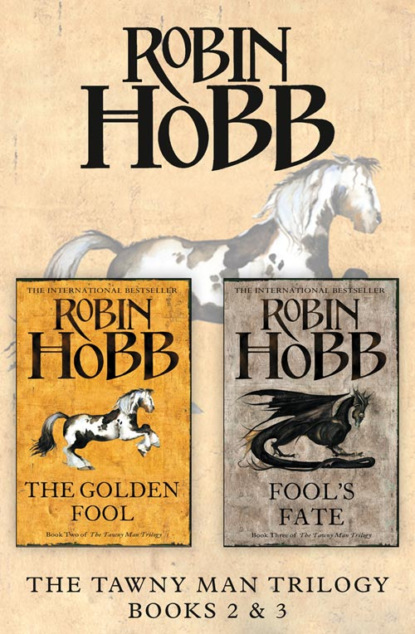

The Tawny Man Series Books 2 and 3: The Golden Fool, Fool’s Fate

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The one time that Chade’s eyes met mine, I glanced pointedly at Rosemary and scowled. But when I looked back for his reaction, he was once more chatting with the lady at his left. I growled to myself, but knew that clarification would come later.

As the end of the meal grew closer, I could feel Dutiful’s tension mounting. The Prince’s smile showed too much of teeth. When the Queen motioned to the minstrel and he called for silence, I saw Dutiful shut his eyes for an instant as if to steel himself to the challenge. Then I took my eyes from him and focused my attention on Elliania. I saw her moisten her lips, and then perhaps she clenched her jaws to still a trembling. The cant of Peottre’s posture made me suspect that he clasped her hand under the table. In any case, she drew a deep breath and then sat up straighter.

It was a simple ceremony. I paid more attention to the faces of those witnessing it. All the participants moved to the front of the high dais. Kettricken stood next to Dutiful, and Arkon Bloodblade by his daughter. Unbidden, Peottre came to stand behind her. When Arkon set his daughter’s hand in the Queen’s, I noticed that Duchess Faith of Bearns narrowed her eyes and clamped her lips. Perhaps Bearns remembered too well how they had suffered in the Red Ship War. There was quite a different reaction from the Duke and Duchess of Tilth. They looked warmly into one another’s eyes as if recalling the moment of their own pledge. Patience sat, still and solemn, her gaze distant. Young Civil Bresinga looked envious, and then turned his eyes away from the sight as if he could not bear to witness it. I saw no one who looked at the couple with malice, though some, like Faith, plainly had their own opinions about this alliance.

The couple’s hands were not joined at this time; rather Elliania’s hand was put in Kettricken’s, and Dutiful and Arkon grasped wrists in the ancient greeting of warriors well met. All seemed a bit surprised when Arkon tugged a gold band from his wrist and clasped it onto Dutiful’s. He guffawed in delight at how it hung on the boy’s lesser-muscled arm, and Dutiful managed a good-natured laugh, and even held it aloft for others to admire. The Outislander delegation seemed to take this as a sign of good spirit in the Prince, for they hammered their table in approval. A slight smile tugged at the corner of Peottre’s mouth. Was it because the bracelet that Arkon had bestowed on Dutiful had a boar scratched on it rather than a narwhal? Was the Prince binding himself to a clan that had no authority over the Narcheska?

Then came the only incident that seemed to mar the smoothness of the ceremony. Arkon gripped the Prince’s wrist and turned it so that the Prince’s hand was palm up. Dutiful tolerated this but I knew his uneasiness. Arkon seemed unaware of it as he asked the assemblage loudly, ‘Shall we mingle their blood now, for sign of the children to come that share it?’

I saw the Narcheska’s intake of breath. She did not step back into Peottre’s shelter. Rather, the man stepped forward and in an unconscious show of possession, set a hand to the girl’s shoulder. His words were unaccented and calm as he said, in apparent good-natured rebuke, ‘It is not the time or the place for that, Bloodblade. The man’s blood must fall on the hearthstones of her mother’s house for that mingling to be auspicious. But you might offer some of your blood to the hearthstones of the Prince’s mother, if you are so minded.’

I suspect there was a hidden challenge in those words, some custom we of the Six Duchies did not comprehend. For when Kettricken began to hold out her hand to say such an act was not necessary, Arkon thrust out his arm. He pushed his sleeve up out of the way, and then casually drew his belt knife and ran the blade down the inside of his arm. At first the thick blood merely welled in the gash. He clawed at the wound and then gave his arm a shake to encourage the flow. Kettricken wisely stood still, allowing the barbarian whatever gesture he thought he must make for the honour of his house. He displayed his arm to the assembly, and in the murmurous awe of all, we watched his cupped hand catch his own trickling blood. He suddenly flung it wide, a red benediction upon us all.

Many cried out as those crimson droplets spattered the faces and garments of the gathered nobility. Then silence fell as Arkon Bloodblade descended from the dais. He strode to the largest hearth in the Great Hall. There he again let his blood pool in his hand, then flung the cupped gore into the flames. Stooping, he smeared his palm across the hearth, and then stood, allowing his sleeve to fall over his injury. He opened his arms to the assembly, inviting a response. At the Outislander table, his people pounded the board and whooped in admiration. After a moment, applause and cheers also rose from the Six Duchies folk. Even Peottre Blackwater grinned, and when Arkon rejoined him on the dais, they grasped wrists before the assemblage.

As I watched them there, I suspected that their relationship was far more complicated than I had first imagined. Arkon was Elliania’s father, yet I doubted that Peottre ceded him any respect on that account. But when they stood as they did now, as fellow warriors, I sensed between them the camaraderie of men who had fought alongside one another. So there was esteem, even if Peottre did not think Arkon had the right to offer Elliania as a treaty-affirming token.

It brought me back full circle to the central mystery. Why did Peottre allow it? Why did Elliania go along with it? If they stood to gain from this alliance, why did not her mothers’ house stand proudly behind it and offer the girl?

I studied the Narcheska as Chade had taught me. Her father’s gesture had caught her imagination. She smiled at him, proud of his valour and the show he had made for the Six Duchies nobles. Part of her enjoyed all this, the pageantry and ceremony, the clothing and the music and the gathered folk all looking up at her. She wanted all the excitement and glory but at the end of it she also wanted to return to what was safe and familiar, to live out the life she expected to live, in her mothers’ house on her mothers’ land. I asked myself, how could Dutiful use that to gain her favour? Were there any plans for him to present himself, with gifts and honours at her mothers’ holding? Perhaps she would think better of him if his attention to her could be flaunted before her maternal relatives back home. Girls usually enjoyed that sort of elevation, didn’t they? I stored up my insights to offer them to Dutiful tomorrow. I wondered if they were accurate, or would be of any use to him.

As I pondered, Queen Kettricken nodded towards her minstrel. He signalled the musicians to ready themselves. Queen Kettricken then smiled and said something to the other folk on the grand dais. Places were resumed and as the music began, Dutiful offered his hand to Elliania.

I pitied them both, so young and so publicly displayed, the wealth of two folks offered to one another as chattel for an alliance. The Narcheska’s hand hovered above Dutiful’s wrist as he escorted her down the steps of the dais to the swept sand of the dance floor. In a brief swell of Skill, I knew that his collar chafed against his sweaty neck, but none of that showed in his smile or in the gracious bow he offered his partner. He held out his arms for her, and she stepped just close enough for his fingertips to graze her waist. She did not put her hands to his shoulders in the traditional stance; rather she held out her skirts as if to better display both them and her lively feet. Then the music swirled around them and they both danced as perfectly as puppets directed by a master. They made a lovely spectacle, full of youth and grace and promise as they stepped and turned together.

I watched those who gazed upon them, and was surprised by the spectrum of emotions I saw in those mirroring faces. Chade beamed with satisfaction but Kettricken’s face was more tentative, and I guessed her secret hope that Dutiful would find true affection as well as solid political advantage in his partner. Arkon Bloodblade crossed his arms on his chest and looked down on the two as if they were a personal testimonial to his power. Peottre, like me, was scanning the crowd, ever the bodyguard and watchman for his ward. He did not scowl, but neither did he smile. For a chance instant, his eyes met mine as I studied him. I dared not look aside, but stared through him with a dull expression as if I did not truly see him at all. His eyes left me to travel back to Elliania and the faintest shadow of a smile crossed his lips.

Drawn by his scrutiny, my gaze followed his. For that moment, I allowed myself to be caught in the spectacle. As they stepped and turned to the music, slippers and skirts swirled the brushed sand on the floor into a fresh pattern. Dutiful was taller than his partner; doubtless it was easier for him to look down into her upturned face than it was for her to gaze up at him and smile and keep the step. He looked as if his outstretched hands and arms framed the flight of a butterfly, so lightly did she move opposite him. A spark of approval kindled in me as well, and I thought I understood why Peottre had given that grudging smile of approval. My lad did not seek to grasp the girl; his touch sketched the window of her freedom as she danced. He did not claim nor attempt to restrain; rather he exhibited her grace and her liberty to those who watched. I wondered where Dutiful had learned such wisdom. Had Chade coached him in this, or was this the diplomatic instinct some Farseers seemed to possess? Then I decided it did not matter. He had pleased Peottre and I suspected that that would eventually be to his advantage.

The Prince and the Narcheska performed alone for the first dance. After that, others moved to join them on the dance floor, the dukes and duchesses of the Six Duchies and our Outislander guests. I noticed that Peottre was true to his word, claiming the Narcheska away from Dutiful for the second dance. That left the Prince standing alone, but he managed to appear graceful and at ease. Chade drifted over to speak with him until the Queen’s advisor was claimed by a maiden of no more than twenty.

Arkon Bloodblade had the effrontery to offer his hand to Queen Kettricken. I saw the look that flickered over her face. She would have refused him, but decided it was not in the best interest of the Six Duchies to do so. So she descended with him to the dance floor. Bloodblade had none of Dutiful’s nicety in the matter of a partner’s preference. He seized the Queen boldly at her waist so that she had to set her hands on his shoulders to balance the man’s lively stepping, or else find herself spinning out of control. Kettricken trod the measure gracefully and smiled upon her partner, but I do not think she truly enjoyed it.

The third measure was a slower dance. I was pleased to see Chade forsake his young partner, who sulked prettily. Instead he invited my Lady Patience out to the floor. She shook her fan at him and would have refused, but the old man insisted, and I knew that she was secretly pleased. She was as graceful as she had ever been – though never quite in step with the music, but Chade smiled down on her as he steered her safely around the floor and I found her dance both lovely and charming.

Peottre rescued Queen Kettricken from Bloodblade’s attention, and he went off to dance with his daughter. Kettricken seemed more at ease with the old man-at-arms than she had with his brother-in-law. They spoke as they danced, and the lively interest in her eyes was genuine. Dutiful’s eyes met mine for an instant. I knew how awkward he felt standing there, a lone stag, while his intended was whirled around the dance floor by her father. But at the end of the dance, I almost suspected that Bloodblade had known of it, and felt a sympathy for the young prince, for he firmly delivered his daughter’s hand to Dutiful’s for the fourth dance.

And so it went. For the most part, the Outislander nobles chose partners from among themselves, though one young woman dared to approach Lord Shemshy. To my surprise, the old man seemed flattered by the invitation, and danced not once with her, but thrice. When the partner dances were over, the patterns began, and the high nobles resumed their seats, ceding the floor to the lesser nobility. I stood silently and watched, for the most part. Several times my master sent me on errands to different parts of the room, usually to deliver his greetings to women and his heartfelt regrets that he could not ask them to dance due to the severity of his injury. Several came to cluster near him and commiserate with him. In all that long evening, I never once saw Civil Bresinga take to the dance floor. Lady Rosemary did, even dancing once with Chade. I watched them speak to one another, she looking up at him and smiling mischievously while his features remained neutral yet courteous. Lady Patience retired early from the festivities, as I had suspected she might. She had never truly felt at home in the pomp and society of court. I thought that Dutiful should feel honoured that she had troubled to come at all.

The music, the dancing, the eating and the drinking, all of it went on and on, past the depths of night and into the shallows of morning. I tried to contrive some way to get close to either Civil Bresinga’s wine glass or his plate, but to no avail. The evening began to drag. My legs ached from standing and I thought regretfully of my dawn appointment with Prince Dutiful. I doubted that he would keep it, and yet I must still be there, in case he appeared. What had I been thinking? I would have been far wiser to put the boy off for a few more days, and use that time to visit my home.

Lord Golden, however, seemed indefatigable. As the evening progressed and the tables were pushed to one side to enlarge the dancing space, he found a comfortable place near a fireside and held his court there. Many and varied were the folk who came to greet him and lingered to talk. Yet again it was driven home to me that Lord Golden and the Fool were two very distinct people. Golden was witty and charming, but he never displayed the Fool’s edged humour. He was also very Jamaillian, urbane and occasionally intolerant of what he bluntly referred to as ‘the Six Duchies attitude’ towards his morality and habits. He discussed dress and jewellery with his cohorts in a way that mercilessly shredded any outside the circle of his favour. He flirted outrageously with women, married or not, drank extravagantly and when offered Smoke, grandly declined on the grounds that ‘any but the finest quality leaves me nauseous in the morning. I was spoiled at the Satrap’s court, I suppose.’ He chattered of doings in far-off Jamaillia in an intimate way that convinced even me that he had not only resided there, but been privy to the doings of their high court.

And as the evening deepened, censers of Smoke, made popular in Regal’s time, began to appear. Smaller styles were in vogue now, little metal cages suspended from chains that held tiny pots of the burning drug. Younger lords and a few of the ladies carried their own little censers, fastened to their wrists. In a few places, diligent servants stood beside their masters, swinging the censers to wreathe their betters with the fumes.

I had never had any head for this intoxicant, and somehow my mental association of Smoke with Regal made it all the more distasteful to me. Yet even the Queen was indulging, moderately, for Smoke was known in the Mountains as well as the Six Duchies, though the herb they burned there was a different one. Different herb, same name, same effects, I thought woozily. The Queen had returned to the high dais, her eyes bright through the haze. She sat talking to Peottre. He smiled and spoke to her, but his eyes never left Elliania as Dutiful led her through a pattern dance. Arkon Bloodblade had also joined them on the floor and was working his way through a succession of dance partners. He had shed his cloak and opened his shirt. He was a lively dancer, not always in step with the music as the Smoke curled and the wine flowed.

I think it was out of mercy for me that Lord Golden announced that the pain in his ankle had wearied him and he must, he feared, retire. He was urged to stay on, and he appeared to consider it, but then decided he was in too much discomfort. Even so, it took an interminable amount of time for him to make his farewells. And when I did take up his footstool and cushion to escort him from the merry-making, we were halted at least four times by yet more folk wishing to bid him good night. By the time we had clambered slowly up the stairs and entered our apartments, I had a much clearer view of his popularity at court.

When the door was safely closed and latched behind us, I built up our dying fire. Then I poured myself a glass of his wine and dropped into a chair by the hearth while he sat down on the floor to unwind the wrappings from his foot.

‘I did this too tight! Look at my poor foot, gone almost blue and cold.’

‘Serves you right,’ I observed without sympathy. My clothing reeked of Smoke. I blew a breath out through my nostrils, trying to clear the scent away. I looked down on him where he sat rubbing his bared toes and realized what a relief it was to have the Fool back. ‘How did you ever come up with “Lord Golden”? I don’t think I’ve ever encountered a more backbiting, conniving noble. If I had met you for the first time tonight, I would have despised you. You put me in mind of Regal.’

‘Did I? Well, perhaps that reflects my belief that there is something to be learned from everyone that we meet.’ He yawned immensely and then rolled his body forward until his brow touched his knees, and then back until his loosened hair swept the floor. With no apparent effort, he came back to a sitting position. He held out his hand to me where I sat and I offered him mine to pull him to his feet. He plopped down in the chair next to mine. ‘There is a lot to be said for being nasty, if you want others to feel encouraged to parade their smallest and most vicious opinions for you.’

‘I suppose. But why would anyone want that?’

He leaned over to pluck the wine glass from my fingers. ‘Insolent churl. Stealing your master’s wine. Get your own glass.’ And as I did so, he replied, ‘By mining such nastiness, I discover the ugliest rumours of the keep. Who is with child by someone else’s lord? Who has run themselves into debt? Who has been indiscreet and with whom? And who is rumoured to be Witted, or to have ties to someone who is?’

I nearly spilled my wine. ‘And what did you hear?’

‘Only what we expected,’ he said comfortingly. ‘Of the Prince and his mother, not a word. Nor any gossip about you. An interesting rumour that Civil Bresinga broke off his engagement to Sydel Grayling because there is supposed to be Wit in her family. A Witted silversmith and his six children and wife were driven out of Buckkeep Town last week; Lady Esomal is quite annoyed, for she had just ordered two rings from him. Oh. And Lady Patience has on her estate three Witted goosegirls and she doesn’t care who knows it. Someone accused one of them of putting a spell on his hawks, and Lady Patience told him that not only did the Wit not work that way, but that if he didn’t stop setting his hawks on the turtledoves in her garden she’d have him horsewhipped, and she didn’t care whose cousin he was.’

‘Ah. Patience is as discreet and rational as ever,’ I said, smiling, and the Fool nodded. I shook my head more soberly as I added, ‘If the tide of feeling rises much higher against the Witted ones, Patience may find she has put herself in danger by taking their part. Sometimes I wish her caution was as great as her courage.’

‘You miss her, don’t you?’ he asked softly.

I took a breath. ‘Yes. I do.’ Even admitting it squeezed my heart. It was more than missing her. I’d abandoned her. Tonight I’d seen her, a fading old woman alone save for her loyal, ageing servants.

‘But you’ve never considered letting her know that you survived? That you live still?’

I shook my head. ‘For the reasons I just mentioned. She has no caution. Not only would she proclaim it from the rooftops, but also she would probably threaten to horsewhip anyone who refused to rejoice with her. That would be after she got over being furious with me, of course.’

‘Of course.’

We were both smiling, in that bittersweet way one does when imagining something that the heart longs for and the head would dread. The fire burned before us, tongues of flame lapping up the side of the fresh log. Outside the shuttered windows, a wind was blowing. Winter’s herald. A twitch of old reflexes made me think of all the things I had not done to prepare for it. I’d left crops in my garden, and harvested no marsh grass for the pony’s winter comfort. They were the cares of another man in another life. Here at Buckkeep, I need worry about none of that. I should have felt smug, but instead I felt divested.

‘Do you think the Prince will meet me at dawn in Verity’s tower?’

The Fool’s eyes were closed but he rolled his head towards me. ‘I don’t know. He was still dancing when we left.’

‘I suppose I should be there in case he does. I wish I hadn’t said I would. I need to get back to my cabin and tidy myself out of there.’

He made a small sound between assent and a sigh. He drew his feet up and curled up in the chair like a child. His knees were practically under his chin.

‘I’m going to bed,’ I announced. ‘You should, too.’

He made another sound. I groaned. I went to his bed, dragged off a coverlet, and brought it back to the fireside. I draped it over him. ‘Good night, Fool.’

He sighed heavily in reply and pulled the blanket closer.

I blew out all the candles save one that I carried to my chamber with me. I set it down on my small clothing chest and sat down on the hard bed with a groan. My back ached all round my scar. Standing still had always irritated it far more than riding or working. The little room was both chill and close, the air too still and full of the same smells it had gathered for the last hundred years. I didn’t want to sleep there. I thought of climbing all the steps to Chade’s workroom and stretching out on the larger, softer bed there. That would have been good, if there had not been so many stairs between it and me.

I dragged off my fine clothes and made an effort at putting them away properly. As I burrowed beneath my single blanket, I resolved to get some money out of Chade and purchase at least one more blanket for myself, one that was not so aggressively itchy. And to check on Hap. And apologize to Jinna for not coming to see her this evening as I had said I would. And get rid of the scrolls in my cabin. And teach my horse some manners. And instruct the Prince in the Skill and the Wit.

I drew a very deep breath, sighed it and all my cares away, and sank into sleep.