По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

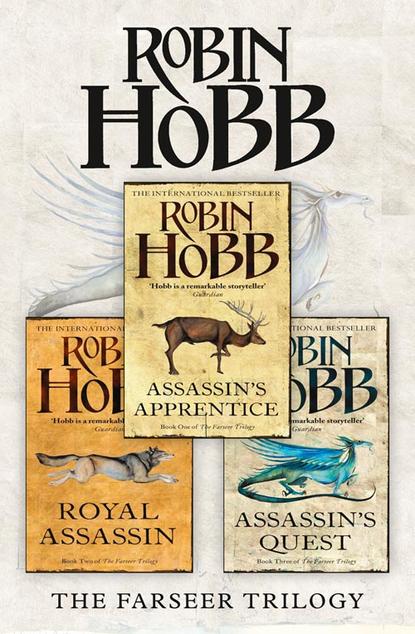

The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I suddenly realized that she thought I was the scriber’s help-boy. I didn’t see any reason to tell her otherwise. ‘Oh, Fedwren uses many things for his dyes and inks. Some copies he makes quite plain, but others are fancy, all done with birds and cats and turtles and fish. He showed me a Herbal with the greens and flowers of each herb done as the border for the page.’

‘That I should dearly love to see,’ she said in a heartfelt way, and I instantly began thinking of ways to purloin it for a few days.

‘I might be able to get you a copy to read … not to keep, but to study for a few days,’ I offered hesitantly.

She laughed, but there was a slight edge in it. ‘As if I could read! Oh, but I imagine you’ve picked up some letters, running about for the scribe’s errands.’

‘A few,’ I told her, and was surprised at the envy in her eyes when I showed her my list and confessed I could read all seven words on it.

A sudden shyness came over her. She walked more slowly, and I realized we were getting close to the chandlery. I wondered if her father still beat her, but dared not ask about it. Her face, at least, showed no sign of it. We reached the chandlery door and paused there. She made some sudden decision, for she put her hand on my sleeve, took a breath and then asked, ‘Do you think you could read something for me? Or even any part of it?’

‘I’ll try,’ I offered.

‘When I … now that I wear skirts, my father has given me my mother’s things. She had been dress-help to a lady up at the keep when she was a girl, and had letters taught her. I have some tablets she wrote. I’d like to know what they say.’

‘I’ll try,’ I repeated.

‘My father’s in the shop.’ She said no more than that, but something in the way her consciousness rang against mine was sufficient.

‘I’m to get Scribe Fedwren two beeswax tapers,’ I reminded her. ‘I dare not go back to the keep without them.’

‘Be not too familiar with me,’ she cautioned me, and then opened the door.

I followed her, but slowly, as if coincidence brought us to the door together. I need not have been so circumspect. Her father slept quite soundly in a chair beside the hearth. I was shocked at the change in him. His skinniness had become skeletal, the flesh on his face reminding me of an undercooked pastry over a lumpy fruit pie. Chade had taught me well. I looked to the man’s fingernails and lips, and even from across the room, I knew he could not live much longer. Perhaps he no longer beat Molly because he no longer had the strength. Molly motioned me to be quiet. She vanished behind the hangings that divided their home from their shop, leaving me to explore the store.

It was a pleasant place, not large, but the ceiling was higher than in most of the shops and dwellings in Buckkeep Town. I suspected it was Molly’s diligence that kept it swept and tidy. The pleasant smells and soft light of her industry filled the room. Her wares hung in pairs by their joined wicks from long dowels on a rack. Fat sensible candles for ships’ use filled another shelf. She even had three glazed, pottery lamps on display, for those able to afford such things. In addition to candles, I found she had pots of honey, a natural by-product of the beehives she tended behind the shop that furnished the wax for her finest products.

Then Molly reappeared and motioned to me to come and join her. She brought a branch of tapers and a set of tablets to a table and set them out on it. Then she stood back and pressed her lips together as if wondering if what she did were wise.

The tablets were done in the old style. Simple slabs of wood had been cut with the grain of the tree and sanded smooth. The letters had been brushed in carefully, and then sealed to the wood with a yellowing rosin layer. There were five, excellently lettered. Four were carefully precise accounts of herbal recipes for healing candles. As I read each one softly aloud to Molly, I could see her struggling to commit them to memory. At the fifth tablet, I hesitated. ‘This isn’t a recipe,’ I told her.

‘Well, what is it?’ she demanded in a whisper.

I shrugged and began to read it to her. ‘“On this day was born my Molly Nosegay, sweet as any bunch of posies. For her birth labours, I burned two tapers of bayberry and two cup-candles scented with two handfuls of the small violets that grow near Dowell’s Mill and one handful of redroot, chopped very fine. May she do likewise when her time comes to bear a child, and her labour will be as easy as mine, and the fruit of it as perfect. So I believe.”’

That was all, and when I had read it, the silence grew and blossomed. Molly took that last tablet from my hands and held it in her two hands and stared at it, as if reading things in the letters that I had not seen. I shifted my feet, and the scuffing recalled to her that I was there. Silently she gathered up all her tablets and disappeared with them once more.

When she came back, she walked swiftly to the shelf and took down two tall beeswax tapers, and then to another shelf whence she took two fat pink candles.

‘I only need …’

‘Shush. There’s no charge for any of these. The sweetberry blossom ones will give you calm dreams. I very much enjoy them, and I think you will, too.’ Her voice was friendly, but as she put them into my basket, I knew she was waiting for me to leave. Still, she walked to the door with me, and opened it softly lest it wake her father. ‘Good-bye, Newboy,’ she said, and then gave me one real smile. ‘Nosegay. I never knew she called me that. Nosebleed, they called me on the streets. I suppose the older ones who knew what name she had given me thought it was funny. And after a while they probably forgot it had ever been anything else. Well. I don’t care. I have it now. A name from my mother.’

‘It suits you,’ I said in a sudden burst of gallantry, and then, as she stared and the heat rose in my cheeks, I hurried away from the door. I was surprised to find that it was late afternoon, nearly evening. I raced through the rest of my errands, begging the last item on my list, a weasel’s skin, through the shutters of the merchant’s window. Grudgingly he opened his door to me, complaining that he liked to eat his supper hot, but I thanked him so profusely he must have believed me a little daft.

I was hurrying up the steepest part of the road back to the keep when I heard the unexpected sound of horses behind me. They were coming up from the dock section of town, ridden hard. It was ridiculous. No one kept horses in town, for the roads were too steep and rocky to make them of much use. Also, the town was crowded into such a small area as to make riding a horse a vanity rather than a convenience. So these must be horses from the keep’s stables. I stepped to one side of the road and waited, curious to see who would risk Burrich’s wrath by riding horses at such speed on slick and uneven cobbles in poor light.

To my shock it was Regal and Verity on the matched blacks that were Burrich’s pride. Verity carried a plumed baton, such as messengers to the keep carried when the news they bore was of the utmost importance. At the sight of me standing quietly beside the road they both pulled in their horses so violently that Regal’s spun aside and nearly went down on his knees.

‘Burrich will have fits if you break that colt’s knees!’ I cried out in dismay and ran toward him.

Regal gave an inarticulate cry, and a half-instant later, Verity laughed at him shakily. ‘You thought he was a ghost, same as I. Whoah, lad, you gave us a turn, standing so quiet as that. And looking so much like him. Eh, Regal?’

‘Verity, you’re a fool. Hold your tongue.’ Regal gave his mount’s mouth a vindictive jerk, and then tugged his jerkin smooth again. ‘What are you doing out on this road so late, bastard? Just what do you think you’re up to, sneaking away from the keep and into town at this hour?’

I was used to Regal’s disdain for me. This sharp rebuke was something new, however. Usually, he did little more than avoid me, or hold himself away from me as if I were fresh manure. The surprise made me answer quickly, ‘I’m on my way back, not to, sir. I’ve been running errands for Fedwren.’ And I held up my basket as proof.

‘Of course you have,’ he sneered. ‘Such a likely tale. It’s a bit too much of a coincidence, bastard.’ Again he flung the word at me.

I must have looked both hurt and confused, for Verity snorted in his bluff way and said, ‘Don’t mind him, boy. You gave us both a bit of a turn. A river ship just came into town, flying the pennant for a special message. And when Verity and I rode down to get it, lo and behold, it’s from Patience, to tell us Chivalry’s dead. Then, as we come up the road, what do we see but the very image of him as a boy, standing silent before us and of course we were in that frame of mind and …’

‘You are such an idiot, Verity!’ Regal spat. ‘Trumpet it out for the whole town to hear before the King’s even been told. And don’t put ideas in the bastard’s head that he looks like Chivalry. From what I hear, he has ideas enough, and we can thank our dear father for that. Come on. We’ve got a message to deliver.’

Regal jerked his mount’s head up again, and then set spurs to him. I watched him go, and for an instant I swear all I thought was that I should go to the stable when I got back to the keep, to check on the poor beast and see how badly his mouth was bruised. But for some reason I looked up at Verity and said, ‘My father’s dead.’

He sat still on his horse. Bigger and bulkier than Regal, he still always sat a horse better. I think it was the soldier in him. He looked at me in silence for a moment. Then he said, ‘Yes. My brother’s dead.’ He granted me that, my uncle, that instant of kinship, and I think that ever after it changed how I saw him. ‘Up behind me, boy, and I’ll take you back to the keep,’ he offered.

‘No, thank you. Burrich would take my hide off for riding a horse double on this road.’

‘That he would, boy,’ Verity agreed kindly. Then, ‘I’m sorry you found out this way. I wasn’t thinking. It does not seem it can be real.’ I caught a glimpse of his true grief, and then he leaned forward and spoke to his horse and it sprang forward. In moments I was alone on the road again.

A fine misting rain began and the last natural light died, and still I stood there. I looked up at the keep, black against the stars, with here and there a bit of light spilling out. For a moment I thought of setting my basket down and running away, running off into the darkness and never coming back. Would anyone ever come looking for me? I wondered. But instead I shifted my basket to my other arm and began my slow trudge back up the hill.

SEVEN (#ulink_e3c42d40-191f-5402-a0e3-52d3eb184d5c)

An Assignment (#ulink_e3c42d40-191f-5402-a0e3-52d3eb184d5c)

There were rumours of poison when Queen Desire died. I choose to put in writing here what I absolutely know as truth. Queen Desire did die of poisoning, but it had been self-administered, over a long period of time, and was none of her king’s doing. Often he had tried to dissuade her from using intoxicants as freely as she did. Physicians had been consulted, as well as herbalists, but no sooner had he persuaded her to desist from one than she discovered another to try.

Towards the end of the last summer of her life, she became even more reckless, using several kinds simultaneously and no longer making any attempts to conceal her habits. Her behaviours were a great trial for Shrewd, for when she was drunk with wine or incensed with smoke, she would make wild accusations and inflammatory statements with no heed at all as to who was present or what the occasion was. One would have thought that her excesses toward the end of her life would have disillusioned her followers. To the contrary, they declared either that Shrewd had driven her to self-destruction, or poisoned her himself. But I can say with complete knowledge that her death was not of the King’s doing.

Burrich cut my hair for mourning. He left it only a finger’s width long. He shaved his own head, even his beard and eyebrows for his grief. The pale parts of his head contrasted sharply with his ruddy cheeks and nose; it made him look very strange, stranger even than the forest men who came to town with their hair stuck down with pitch and their teeth dyed red and black. Children stared at those wild men and whispered to one another behind their hands as they passed, but they cringed silently from Burrich. I think it was his eyes. I’ve seen holes in a skull that had more life in them than Burrich’s eyes had during those days.

Regal sent a man to rebuke Burrich for shaving his head and cutting my hair. That was mourning for a crowned king, not for a man who had abdicated the throne. Burrich stared at the man until he left. Verity cut a hand’s width from his hair and beard, as that was mourning for a brother. Some of the keep guards cut varying lengths from their braided queues of hair, as a fighting man does for a fallen comrade. But what Burrich had done to himself and to me was extreme. People stared. I wanted to ask him why I should mourn for a father I had never even seen; for a father who had never come to see me, but a look at his frozen eyes and mouth and I hadn’t dared. No one mentioned to Regal the mourning lock he cut from each horse’s mane, or the stinking fire that consumed all the sacrificial hair. I had a sketchy idea that meant Burrich was sending parts of our spirits along with Chivalry’s; it was some custom he had from his grandmother’s people.

It was as if Burrich had died. A cold force animated his body, performing all his tasks flawlessly but without warmth or satisfaction. Underlings who had formerly vied for the briefest nod of praise from him now turned aside from his glance, as if shamed for him. Only Vixen did not forsake him. The old bitch slunk after him wherever he went, unrewarded by any look or touch, but always there. I hugged her once, in sympathy, and even dared to quest toward her, but I encountered only a numbness frightening to touch minds with. She grieved with her master.

The winter storms cut and snarled around the cliffs. The days possessed a lifeless cold that denied any possibility of spring. Chivalry was buried at Withywoods. There was a Grieving Fast at the keep, but it was brief and subdued. It was more an observation of correct form than a true Grieving. Those who truly mourned him seemed to be judged guilty of poor taste. His public life should have ended with his abdication; how tactless of him to draw further attention to himself by actually dying.

A full week after my father died I awoke to the familiar draught from the secret staircase and the yellow light that beckoned me. I rose and hastened up the stairs to my refuge. It would be good to get away from all the strangeness, to mingle herbs and make strange smokes with Chade again. I needed no more of the odd suspension of self that I’d felt since I’d heard of Chivalry’s death.

But the worktable end of his chamber was dark, its hearth was cold. Instead, Chade was seated before his own fire. He beckoned to me to sit beside his chair. I sat and looked up at him, but he was staring at the fire. He lifted his scarred hand and let it come to rest on my quillish hair. For a while we just sat like that, watching the fire together.

‘Well, here we are, my boy,’ he said at last, and then nothing more, as if he had said all he needed to. He ruffled my short hair.

‘Burrich cut my hair,’ I told him suddenly.

‘So I see.’