По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

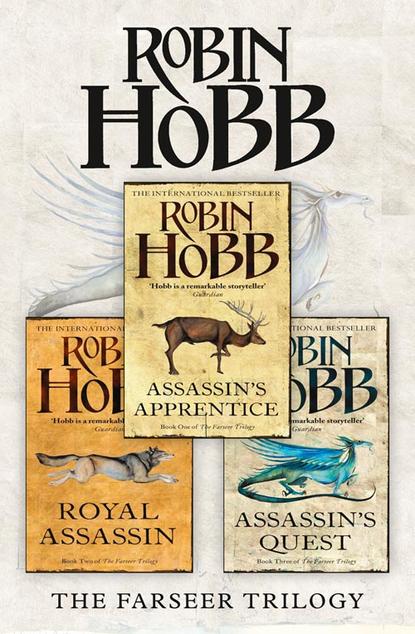

The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Seven: An Assignment (#u471c1e3b-c88a-5c4d-b2bf-fd6e7769f819)

Eight: Lady Thyme (#uc524a713-1411-5ad3-9323-057512f98c44)

Nine: Fat Suffices (#u66889bba-9ed8-57db-b3d5-9a407e3a4178)

Ten: The Pocked Man (#udd101638-3b0e-5bc2-af49-5715783a3842)

Eleven: Forgings (#u197ed2f2-4525-544a-8fb2-23335d1c7c96)

Twelve: Patience (#ud56bbeef-9791-5c23-a473-98d20c5af2a3)

Thirteen: Smithy (#ue91bcb00-409f-57e1-87f8-09ad99fadf07)

Fourteen: Galen (#u59321ce8-f4f9-5035-8bcb-8035886be318)

Fifteen: The Witness Stones (#u2df24884-e891-5f84-b88c-205b0e7620a8)

Sixteen: Lessons (#u52e7b61a-3759-516a-b066-509b711bd3c3)

Seventeen: The Trial (#u53e2e26e-bdee-5708-b206-a89b6935e6f1)

Eighteen: Assassinations (#ue42c3fb4-6f77-5086-9c28-d413e6b995a0)

Nineteen: Journey (#u2972ba05-6acf-5c86-adc2-8a5c7baa0251)

Twenty: Jhaampe (#u22c0d140-31a8-5fcd-89b7-b1010f8562d9)

Twenty-one: Princes (#ue3eedb4c-11f7-5a57-a74f-a8747a35df36)

Twenty-two: Dilemmas (#uf4b1b38e-1bd8-5540-a5f0-629102a2a951)

Twenty-three: The Wedding (#u2fbfe2ef-0f59-55a7-985c-37bae61ebf39)

Twenty-four: The Aftermath (#u8ec66166-dbec-5862-9a36-54a332e0179e)

Epilogue (#u7090d4ba-e6f5-55d9-a34d-28e6e586822e)

ONE (#ulink_c1dff4d1-7ce3-5856-b8f3-2ca4d34383fd)

The Earliest History (#ulink_c1dff4d1-7ce3-5856-b8f3-2ca4d34383fd)

A history of the Six Duchies is of necessity a history of its ruling family, the Farseers. A complete telling would reach back beyond the founding of the First Duchy, and if such names were remembered, would tell us of Outislanders raiding from the Sea, visiting as pirates a shore more temperate and gentler than the icy beaches of the Out Islands. But we do not know the names of these earliest forebears.

And of the first real king, little more than his name and some extravagant legends remain. Taker his name was, quite simply, and perhaps with that naming began the tradition that daughters and sons of his lineage would be given names that would shape their lives and beings. Folk beliefs claim that such names were sealed to the newborn babes by magic, and that these royal offspring were incapable of betraying the virtues whose names they bore. Passed through fire and plunged through salt water and offered to the winds of the air; thus were names sealed to these chosen children. So we are told. A pretty fancy, and perhaps once there was such a ritual, but history shows us this was not always sufficient to bind a child to the virtue that named it …

My pen falters, then falls from my knuckly grip, leaving a worm’s trail of ink across Fedwren’s paper. I have spoiled another leaf of the fine stuff, in what I suspect is a futile endeavour. I wonder if I can write this history, or if on every page there will be some sneaking show of a bitterness I thought long dead. I think myself cured of all spite, but when I touch pen to paper, the hurt of a boy bleeds out with the sea-spawned ink, until I suspect each carefully formed black letter scabs over some ancient scarlet wound.

Both Fedwren and Patience were so filled with enthusiasm whenever a written account of the history of the Six Duchies was discussed that I persuaded myself the writing of it was a worthwhile effort. I convinced myself that the exercise would turn my thoughts aside from my pain and help the time to pass. But each historical event I consider only awakens my own personal shades of loneliness and loss. I fear I will have to set this work aside entirely, or else give in to reconsidering all that has shaped what I have become. And so I begin again, and again, but always find that I am writing of my own beginnings rather than the beginnings of this land. I do not even know to whom I try to explain myself. My life has been a web of secrets, secrets that even now are unsafe to share. Shall I set them all down on fine paper, only to create from them flame and ash? Perhaps.

My memories reach back to when I was six years old. Before that, there is nothing, only a blank gulf no exercise of my mind has ever been able to pierce. Prior to that day at Moonseye, there is nothing. But on that day they suddenly begin, with a brightness and detail that overwhelms me. Sometimes it seems too complete, and I wonder if it is truly mine. Am I recalling it from my own mind, or from dozens of retellings by legions of kitchen maids and ranks of scullions and herds of stable-boys as they explained my presence to each other? Perhaps I have heard the story so many times, from so many sources, that I now recall it as an actual memory of my own. Is the detail the result of a six-year-old’s open absorption of all that goes on around him? Or could the completeness of the memory be the bright overlay of the Skill, and the later drugs a man takes to control his addiction to it, the drugs that bring on pains and cravings of their own? The last is most possible. Perhaps it is even probable. One hopes it is not the case.

The remembrance is almost physical; the chill greyness of the fading day, the remorseless rain that soaked me, the icy cobbles of the strange town’s streets, even the callused roughness of the huge hand that gripped my small one. Sometimes I wonder about that grip. The hand was hard and rough, trapping mine within it. And yet it was warm, and not unkind, as it held mine. Only firm. It did not let me slip on the icy streets, but it did not let me escape my fate, either. It was as implacable as the freezing grey rain that glazed the trampled snow and ice of the gravelled pathway outside the huge wooden doors of the fortified building that stood like a fortress within the town itself.

The doors were tall, not just to a six-year-old boy, but tall enough to admit giants, to dwarf even the rangy old man who towered over me. And they looked strange to me, although I cannot summon up what type of door or dwelling would have looked familiar. Only that these, carved and bound with black iron hinges, decorated with a buck’s head and knocker of gleaming brass, were beyond my experience. I recall that slush had soaked through my clothes, so that my feet and legs were wet and cold. And yet, again, I cannot recall that I had walked far through winter’s last curses, nor that I had been carried. No, it all starts there, right outside the doors of the stronghouse, with my small hand trapped inside the tall man’s.

Almost, it is like a puppet show beginning. Yes, I can see it thus. The curtains parted, and there we stood before that great door. The old man lifted the brass knocker and banged it down, once, twice, thrice, on the plate that resounded to his pounding. And then, from off-stage, a voice sounded. Not from within the doors, but from behind us, back the way we had come. ‘Father, please,’ the woman’s voice begged. I turned to look at her, but it had begun to snow again, a lacy veil that clung to eyelashes and coatsleeves. I can’t recall that I saw anyone. Certainly, I did not struggle to break free of the old man’s grip on my hand, nor did I call out, ‘Mother, Mother!’ Instead I stood, a spectator, and heard the sound of boots within the keep, and the unfastening of the door hasp within.

One last time she called. I can still hear the words perfectly, the desperation in a voice that now would sound young to my ears. ‘Father, please, I beg you!’ A tremor shook the hand that gripped mine, but whether of anger or some other emotion, I shall never know. As swift as a black crow seizes a bit of dropped bread, the old man stooped and snatched up a frozen chunk of dirty ice. Wordlessly he flung it, with great force and fury, and I cowered where I stood. I do not recall a cry, nor the sound of struck flesh. What I do remember is how the doors swung outward, so that the old man had to step hastily back, dragging me with him.

And there is this: the man who opened the door was no house-servant, as I might imagine if I had only heard this story. No, memory shows me a man-at-arms, a warrior, gone a bit to grey and with a belly more of hard suet than muscle, but not some mannered house-servant. He looked both the old man and me up and down with a soldier’s practised suspicion, and then stood there silently, waiting for us to state our business.

I think it rattled the old man a bit, and stimulated him, not to fear, but to anger. For he suddenly dropped my hand and instead gripped me by the back of my coat and swung me forward, like a whelp offered to a prospective new owner. ‘I’ve brought the boy to you,’ he said in a rusty voice.

And when the house-guard continued to stare at him, without judgement or even curiosity, he elaborated. ‘I’ve fed him at my table for six years, and never a word from his father, never a coin, never a visit, though my daughter gives me to understand he knows he fathered a bastard on her. I’ll not feed him any longer, nor break my back at a plough to keep clothes on his back. Let him be fed by him what got him. I’ve enough to tend to of my own, what with my woman getting on in years, and this one’s mother to keep and feed. For not a man will have her now, not a man, not with this pup running at her heels. So you take him, and give him to his father.’ And he let go of me so suddenly that I sprawled to the stone doorstep at the guard’s feet. I scrabbled to a sitting position, not much hurt that I recall, and looked up to see what would happen next between the two men.

The guard looked down at me, lips pursed slightly, not in judgement but merely considering how to classify me. ‘Whose get?’ he asked, and his tone was not one of curiosity, but only that of a man who asks for more specific information on a situation, in order to report well to a superior.

‘Chivalry’s,’ the old man said, and he was already turning his back on me, taking his measured steps down the flagstoned pathway. ‘Prince Chivalry,’ he said, not turning back as he added the qualifier. ‘Him what’s King-in-Waiting. That’s who got him. So let him do for him, and be glad he managed to father one child, somewhere.’

For a moment the guard watched the old man walking away. Then he wordlessly stooped to seize me by the collar and drag me out of the way so that he could close the door. He let go of me for the brief time it took him to secure the door. That done, he stood looking down on me. No real surprise, only a soldier’s stoic acceptance of the odder bits of his duty. ‘Up, boy, and walk,’ he said.

So I followed him, down a dim corridor, past rooms spartanly furnished, with windows still shuttered against winter’s chill, and finally to another set of closed doors, these of rich, mellow wood embellished with carvings. There he paused, and straightened his own garments briefly. I remember quite clearly how he went down on one knee, to tug my shirt straight and smooth my hair with a rough pat or two, but whether this was from some kind-hearted impulse that I make a good impression, or merely a concern that his package look well-tended, I will never know. He stood again, and knocked once at the double doors. Having knocked, he did not wait for a reply, or at least I never heard one. He pushed the doors open, herded me in before him, and shut the doors behind him.

This room was as warm as the corridor had been chill, and alive as the other chambers had been deserted. I recall a quantity of furniture in it, rugs and hangings, and shelves of tablets and scrolls overlain with the scattering of clutter that any well-used and comfortable chamber takes on. There was a fire burning in a massive fireplace, filling the room with heat and a pleasantly rosinous scent. An immense table was placed at an angle to the fire, and behind it sat a stocky man, his brows knit as he bent over a sheaf of papers in front of him. He did not look up immediately, and so I was able to study his rather bushy disarray of dark hair for some moments.

When he did look up, he seemed to take in both myself and the guard in one quick glance of his black eyes. ‘Well, Jason?’ he asked, and even at that age I could sense his resignation to a messy interruption. ‘What’s this?’

The guard gave me a gentle nudge on the shoulder that propelled me a foot or so closer to the man. ‘An old ploughman left him, Prince Verity, sir. Says it’s Prince Chivalry’s bastid, sir.’

For a few moments the harried man behind the desk continued to regard me with some confusion. Then something very like an amused smile lightened his features and he rose and came around the desk to stand with his fists on his hips, looking down on me. I did not feel threatened by his scrutiny; rather it was as if something about my appearance pleased him inordinately. I looked up at him curiously. He wore a short dark beard, as bushy and disorderly as his hair, and his cheeks were weathered above it. Heavy brows were raised above his dark eyes. He had a barrel of a chest, and shoulders that strained the fabric of his shirt. His fists were square and work-scarred, yet ink stained the fingers of his right hand. As he stared at me, his grin gradually widened, until finally he gave a snort of laughter.

‘Be damned,’ he finally said. ‘Boy does have Chiv’s look to him, doesn’t he? Fruitful Eda. Who’d have believed it of my illustrious and virtuous brother?’

The guard made no response at all, nor was one expected from him. He continued to stand alertly, awaiting the next command. A soldier’s soldier.

The other man continued to regard me curiously. ‘How old?’ he asked the guard.

‘Ploughman says six.’ The guard raised a hand to scratch at his cheek, then suddenly seemed to recall he was reporting. He dropped his hand. ‘Sir,’ he added.

The other didn’t seem to notice the guard’s lapse in discipline. The dark eyes roved over me, and the amusement in his smile grew broader. ‘So make it seven years or so, to allow for her belly to swell. Damn. Yes. That was the first year the Chyurda tried to close the pass. Chivalry was up this way for three, four months, chivvying them into opening it to us. Looks like it wasn’t the only thing he chivvied open. Damn. Who’d have thought it of him?’ He paused, then, ‘Who’s the mother?’ he demanded suddenly.

The guardsman shifted uncomfortably. ‘Don’t know, sir. There was only the old ploughman on the doorstep, and all him said was that this was Prince Chivalry’s bastid, and he wasn’t going to feed him ner put clothes on his back no more. Said him what got him could care for him now.’

The man shrugged as if the matter were of no great importance. ‘The boy looks well tended. I give it a week, a fortnight at most before she’s whimpering at the kitchen door because she misses her pup. I’ll find out then if not before. Here, boy, what do they call you?’

His jerkin was closed with an intricate buckle shaped like a buck’s head. It was brass, then gold, then red as the flames in the fireplace moved. ‘Boy,’ I said. I do not know if I were merely repeating what he and the guardsman had called me, or if I truly had no name besides the word. For a moment the man looked surprised and a look of what might have been pity crossed his face. But it disappeared as swiftly, leaving him looking only discomfited, or mildly annoyed. He glanced back at the map that still awaited him on the table.

‘Well,’ he said into the silence. ‘Something’s got to be done with him, at least until Chiv gets back. Jason, see the boy’s fed and bedded somewhere, at least for tonight. I’ll give some thought to what’s to be done with him tomorrow. Can’t have royal bastards cluttering up the countryside.’