По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

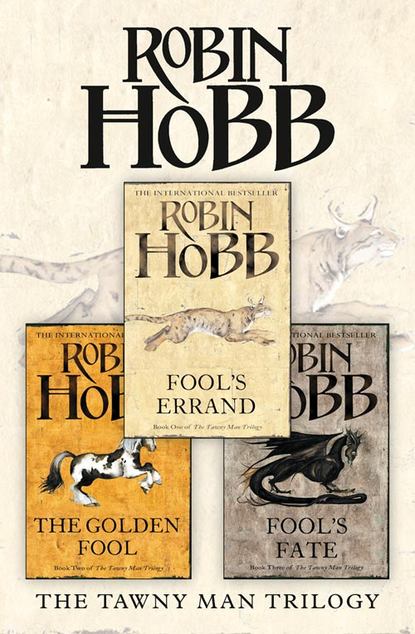

The Complete Tawny Man Trilogy: Fool’s Errand, The Golden Fool, Fool’s Fate

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He was not rational, and I felt both Molly’s anger and her fear for him. She brought him water, and I fussed when she half-sat him up to drink it. I tried to drink from the cup she held to my mouth, but my lips were cracked and sore, my head hurt too badly and the light was too bright. When I pushed it away, the water slopped on my chest, icy cold and I shrieked and began to wail. ‘Nettle, Nettle, hush,’ she bade me, but her hands were cold when she touched me. I wanted nothing of my mother just then, and knew an echo of Nettle’s jealousy that another child claimed the throne of Molly’s lap now. I clutched at Burrich’s shirt and he held me close again and hummed softly in his deep voice. I pushed my face against him where the light could not touch my eyes, and tried to sleep.

I tried so desperately to sleep that I pushed myself into wakefulness. I opened my eyes to my breath rasping in and out of my lungs. Sweat cloaked me, but I could not forget the tightness of my hot, dry skin in the Skill-dream. I had wrapped my cloak about me when I lay down to sleep; now I fought clear of its confines. We had chosen to sleep away the deep of the night on a creek bank; I staggered to the water and drank deeply. When I lifted my face from the water, I found the wolf sitting very straight and watching me. His tail neatly wrapped all four of his feet.

‘He already knew I had to go to them. We set out that night.’

‘And you knew where to go, to find them?’

I shook my head. ‘No. I knew nothing, other than that when they first left Buckkeep, they had settled near a town called Capelin Beach. And I knew the, well, the “feel” of where they lived then. With no more than that, we set out.

‘After years of wandering, it was odd to have a destination, and especially to hurry towards it. I did not think about what we did, or how foolish it was. A part of me admitted it was senseless. We were too far away. I’d never get there in time. By the time I arrived, they would be either dead or recovered. Yet having begun that journey, I could not deviate from it. After years of fleeing any who might recognize me, I was suddenly willing to hurl myself back into their lives again? I refused to consider any of it. I simply went.’

The Fool nodded sympathetically at my account. I feared he guessed far more than I willingly told him.

After years of denying and refusing the lures of the Skill, I immersed myself in it. The addiction clutched at me and I embraced it in return. It was disconcerting to have it come back upon me with such force. But I did not fight it. Despite the blinding headaches that still followed my efforts, I reached towards Molly and Burrich almost every evening. The results were not encouraging. There is nothing like the heady rush of two Skill-trained minds meeting. But Skill-seeing is another matter entirely. I had never been instructed in that application of the Skill; I had only the knowledge I had gained by groping. My father had sealed off Burrich to the Skill, lest anyone try to use his friend against him. Molly had no aptitude for it that I knew. In Skill-seeing them, there could be no true connection of minds, but only the frustration of watching them, unable to make them aware of me. I soon found that I could not achieve even that reliably. Disused, my abilities had rusted. Even a short effort left me exhausted and debilitated by pain, and yet I could not resist trying. I strove for those brief connections and mined them for information. A glimpse of hills behind their home, the smell of the sea, black-faced sheep pastured on a distant hill – I treasured every hint of their surroundings, and hoped they would be enough to guide me to them. I could not control my seeing. Often I found myself watching the homeliest of tasks, the daily labour of a tub of laundry to be washed and hung, herbs to be harvested and dried, and yes, beehives to tend. Glimpses of a baby Molly called Chiv whose face reflected Burrich’s features cut me with both jealousy and wonder.

Eventually I found a village called Capelin Beach. I found the deserted cottage where my daughter had been born. Other folk had lived here since then; no recognizable trace of them remained to my eyes, but the wolf’s nose was keener. Nevertheless, Molly and Burrich were long gone from there, and I knew not where. I dared not ask direct questions in the village, for I did not want anyone to bear word to Burrich or Molly that someone was looking for them. Months had passed in my journeying. In every village I passed, I saw signs of new graves. Whatever the sickness had been, it had spread wide and taken many with it. In none of my visions had I seen Nettle; had it carried her off as well? I spiralled out from Capelin Beach, visiting inns and taverns in nearby villages. I became a slightly daft traveller, obsessed with beekeeping and professing to know all there was to know on the topic. I started arguments so others would correct me and speak of beekeepers they had known. Yet all my efforts to hear the slightest rumour of Molly were fruitless until late one afternoon I followed a narrow road to the crest of the hill, and suddenly recognized a stand of oak trees.

All my courage vanished in that instant. I left the road and skulked through the forested hills that flanked it. The wolf came with me, unquestioning, not even letting his thoughts intrude on mine as I stalked my old life. By early evening, we were on a hillside looking down on their cottage. It was a tidy and prosperous stead, with chickens scratching in the side yard and three straw hives in the meadow behind it. There was a well-tended vegetable garden. Behind the cottage were a barn, obviously a newer structure, and several small paddocks built of skinned logs. I smelled horse. Burrich had done well for them. I sat in the dark and watched the single window glow yellow with candlelight, and then wink to blackness. The wolf hunted alone that night as I kept my vigil. I could not approach and I could not leave. I was caught where I was, a leaf on the edge of their eddy. I suddenly understood all the legends of ghosts doomed to forever haunt some spot. No matter how far I roamed, some part of me would always be chained here.

As dawn broke, Burrich emerged from the cottage door. His limp was more pronounced than I recalled it, as was the streak of white in his hair. He lifted his face to the dawning day and took a great breath, and for one wolfish instant, I feared he would scent me there. But he only walked to the well and drew up a bucket of water. He carried it inside, then returned a moment later to throw some grain to the chickens. The smoke of an awakened fire rose from the chimney. So. Molly was up and about also. Burrich went out to the barn. As clear as if I were walking beside him, I knew his routine. After he had checked every animal, he would come outside. He did, and drew water, carrying bucket after bucket into the barn.

My words choked me for an instant. Then I laughed aloud. My eyes swam with tears but I ignored them. ‘I swear, Fool, that is when I came closest to going down to him. It seemed as unnatural a thing as I had ever done, to watch Burrich work and not toil alongside him.’

The Fool nodded, silent and rapt beside me.

‘When he came out, he was leading a roan stallion. It astonished me. “Buckkeep’s best” shouted every line of his body. His spirit was in the arch of his neck, his power in his shoulders and haunches. My heart swelled in me just to see such a horse, and to know he was in Burrich’s keeping rejoiced me. He turned the horse loose in a paddock, and then hauled yet more water to the trough there.

‘When he next led Ruddy out, much of the mystery was cleared for me. I did not know, then, that Starling had hunted him down and seen to it that both his horse and Sooty’s colt were given over to him. It was just good to see man and horse together again. Ruddy looked to have settled into good-natured stability; even so, Burrich did not paddock him next to the other stud, but put him as far away as possible. He hauled more water for Ruddy, then gave him a friendly thump and went back into the cottage.

‘Then Molly came out.’

I took another breath and held it. I stared out at the ocean, but that was not what I saw. The image of she who had been my woman moved before my eyes. Her dark hair, once wild and blowing to the wind, was braided and pinned sedately to her head, a matron’s crown. A little boy toddled unsteadily after her. Basket on her arm, she moved with placid grace towards the garden. Her white apron draped her swelling pregnancy. The swift and slender girl was gone, but I found this woman no less attractive. My heart yearned after her and all she represented: the cosy hearth and the settled home, the companionship of the years to come as she filled her man’s home with children and warmth.

‘I whispered her name. It was so strange. She lifted her head suddenly, and for one sharp moment I thought she was aware of me. But instead of looking up to the hill, she laughed aloud, and exclaimed, “Chivalry, no! Not good to eat.” She stooped slightly, to pull a handful of pea flowers from the child’s mouth. She lifted him, and I saw the effort it cost her. She called back to the cottage, “My love, come fetch your son before he pulls the whole garden up. Tell Nettle to come and pull some turnips for me.”

‘Then I heard Burrich call back, “A moment!” An instant later, he stood in the doorway. He called over his shoulder, “We’ll finish the washing up later. Come help your mother.” I watched him cross the yard in a few strides and snatch up his son. He swung him high, and the child gave a whoop of delight as Burrich landed him on his shoulder. Molly set a hand upon her belly and laughed with them, looking up at them both with delight in her eyes.’

I stopped speaking. I could no longer see the ocean. Tears blinded me like a fog.

I felt the Fool’s hand on my shoulder. ‘You never went down to them, did you?’

I shook my head mutely.

I had fled. I had fled the sudden gnawing envy I felt, and I fled lest I glimpse my own child and have to go to her. There was no place down there for me, not even on the edges of their world. I knew that. I had known it since first I knew they would marry. If I walked down to that door, I would carry destruction and misery with me.

I am no better than any other man. There was bitterness in me, and anger at both of them, and the stark loneliness of how fate had betrayed us all. I could not blame them for turning to each other. Neither did I blame myself for the anguish I felt that by that act, they had excluded me forever from their lives. It was done, and over, and regrets were useless. The dead, I told myself, have no rights to regret. The most I can claim for myself is that I did walk away. I did not let my pain poison their happiness, or compromise my daughter’s home. That much strength, I found.

I drew a long breath and found my voice again. ‘And that is the end of my tale, Fool. Next winter caught us here. We found this hut and settled into it. And here we have been ever since.’ I blew out a breath and thought over my own words. Suddenly none of it seemed admirable.

His next words rattled me. ‘And your other child?’ he asked quietly.

‘What?’

‘Dutiful. Have you seen him? Is not he your son, just as much as Nettle is your daughter?’

‘I … no. No, he is not. And I have never seen him. He is Kettricken’s son and Verity’s heir. So Kettricken recalls it, I am sure.’ I felt myself reddening, embarrassed that the Fool had brought this up. I set my hand to his shoulder. ‘My friend, only you and I know of how Verity used me … my body. When he asked my permission, I misunderstood his request. I myself have no memory of how Dutiful was conceived. You must recall; I was with you, trapped in Verity’s misused flesh. My king did what he did to get himself an heir. I do not begrudge it, but neither do I wish to remember it.’

‘Starling does not know? Nor even Kettricken?’

‘Starling slept that night. I am sure that if she even suspected, she would have spoken of it by now. A minstrel could not leave such a song unsung, however unwise it might be. As for Kettricken, well, Verity burned with the Skill like a bonfire. She saw only her king in her bed that night. I am certain that if it had been otherwise …’ I sighed suddenly and admitted, ‘I feel shamed to have been a party to that deception. I know it is not my place to question Verity’s will in this, but still …’ My words trickled away. Not even to the Fool could I admit the curiosity I felt about Dutiful. A son, mine and not mine. And as my father had chosen with me, so had I with him. To not know him, for the sake of protecting him.

The Fool set his hand on top of mine and squeezed it firmly. ‘I have spoken of this to no one. Nor shall I.’ He took a deep breath. ‘So. Then you came to this place, to settle yourself in peace. That is truly the end of your tale?’

It was. Since the last time I had bid the Fool farewell, I had spent most of my days either running or hiding. This cottage was my selfish retreat. I said as much.

‘I doubt that Hap would see it that way,’ he returned mildly. ‘And most folks would find saving the world once in their lifetime a sufficient credit and would not think to do more than that. Still, as your heart seems set on it, I will do all I can to drag you through it again.’ He quirked an eyebrow at me invitingly.

I laughed, but not easily. ‘I don’t need to be a hero, Fool. I’d settle for feeling that what I did every day had significance to someone besides myself.’

He leaned back on my bench and considered me gravely for a moment. Then he shrugged one shoulder. ‘That’s easily done, then. Once Hap is settled in his apprenticeship, come find me at Buckkeep. I promise, you’ll be significant.’

‘Or dead, if I’m recognized. Have not you heard how strong feelings run against the Witted these days?’

‘No. I had not. But it does not surprise me, no, not at all. But recognized? You spoke of that worry before, but in a different light. I find myself forced to agree with Starling. I think few would remark you. You look very little like the FitzChivalry Farseer that folk would recall from fifteen years ago. Your face bears the tracks of the Farseer bloodline, if one knows to look for them, but the court is an in-bred place. Many a noble carries a trace of that same heritage. Who would a chance beholder compare you to; a faded portrait in a darkened hall? You are the only grown man of your line still alive. Shrewd wasted away years ago, your father retired to Withywoods before he was killed, and Verity was an old man before his time. I know who you are, and hence I see the resemblance. I do not think you are in danger from the casual glance of a Buckkeep courtier.’ He paused, then asked me earnestly, ‘So. I will see you in Buckkeep before snow flies?’

‘Perhaps,’ I hedged. I doubted it, but knew better than to waste breath arguing with the Fool.

‘I shall,’ he decided resolutely. Then he clapped me on the shoulder. ‘Let’s back. Supper should be ready. And I want to finish my carving.’

TEN A Sword and a Summons (#ulink_d4549d18-4b6b-50b5-bbaf-e3ba09777ffe)

Perhaps every kingdom has its tales of a secret and powerful protector, one that will rise to the land’s defence if the need be great and the entreaty sincere enough. In the Out Islands, they speak of Icefyre, a creature who dwells deep in the heart of the glacier that cloaks the heart of Island Aslevjal. They swear that when earthquakes shake their island home, it is Icefyre rolling restlessly in his chill dreams deep within his ice-bound lair. The Six Duchies legends always referred to the Elderlings, an ancient and powerful race who dwelt somewhere beyond the Mountain Kingdom and were our allies in times of old. Only a king as desperate as King-in-Waiting Verity Farseer would have given such legends not only credence, but enough importance that he left his legacy in the care of his ailing father and foreign queen while he made a quest to seek the aid of the Elderlings. Perhaps it was that desperate faith that gave him the power not only to wake the Elderling-carved stone dragons and rally them to the Six Duchies’ aid, but also to carve for himself a dragon body and lead them to defend his land.

The Fool stayed on, but in the days that followed, he studiously avoided any serious topics or tasks. I fear I followed his example. Telling him of my quiet years seemed to settle those old ghosts. I should have been content to slip back into my old routines but instead a different sort of restlessness itched. A changing time, and a time to change. Changer. The Catalyst. The words and the thoughts that went with them wound through my days and tangled my dreams at night. I was no longer tormented by my past so much as taunted by the future. Looking back over what I had made of my own youth, I suddenly found myself much concerned for how Hap would spend his years. It suddenly seemed to me that I had wasted all the years when I should have been preparing the lad to face a life on his own. He was a good-hearted young man, and I had no qualms about his character. My worry was that I had given him only the most basic knowledge of making his way in the world. He had no specialized skills to build on. He knew all that he needed to know to live in an isolated cottage and farm and hunt for his basic needs. But it was the wide world I was sending him into; how would he make his way there? The need to apprentice him well began to keep me awake at night.

If the Fool was aware of this, he gave no sign of it. His busy tools wandered through my cabin, sending vinework crawling across my mantelpiece. Lizards peered down from the door lintel. Odd little faces leered at me from the corners of cupboard doors and the edge of the porch steps. If it was made of wood, it was not safe from his sharp tools and clever fingers. The activities of the water sprites on my rain barrel would have made a guardsman blush.

I chose quiet work for myself as well, and toiled indoors as much as out despite the fine weather. Part of it was that I felt I needed a thoughtful time, but the greater share was that the wolf was slow to recover his strength. I knew that my watching over him would not hasten his healing, but I could not chase away my anxiety for him. When I reached for him with the Wit, there was a sombre quality to his silence, most unlike my old companion. Sometimes I would look up from my work to find him watching me, his deep eyes pensive. I did not ask him what he was thinking; if he had wanted to share it, his mind would have been accessible to mine.

Gradually, he regained his old activities, but some of the spring had gone out of him. He moved with a care for his body, never challenging himself. He did not follow me about my chores, but lay on the porch and watched my comings and goings. We hunted together still in the evening, but we went more slowly, both pretending to be hampered by the Fool. Nighteyes was as often content to point out the game and wait for my arrow rather than spring to the kill himself. These changes troubled me, but I did my best to keep my concerns to myself. All he needed was time to heal, I told myself, and recalled that the hot days of summer had never been his best time. When autumn came, he would recover his old vigour.

The three of us were settling into a comfortable routine. There were tales and stories in the evening, an accounting of the lesser events in our lives. Eventually we ran out of brandy, but the talk still flowed as smooth and warming as the liquor had. I told the Fool what Hap had seen at Hardin’s Spit, and of the talk about the Witted in the market. I shared, too, Starling’s account of the minstrels at Springfest, and Chade’s assessment of Prince Dutiful and what he had asked of me. All these stories, the Fool seemed to take into himself as a weaver takes up divergent threads to create from them a tapestry.

We tried the rooster feathers in the crown one evening, but the shafts of the feathers were too thin for the sockets, so the feathers sprawled in all directions. We both knew without speaking that they were completely wrong. Another evening, the Fool set out the crown on my table, and selected brushes and inks from my stores. I took a chair to one side to watch him. He arranged all carefully before him, dipped a brush in blue ink, and then paused, thinking. We sat still and silent so long that I became aware of the sounds of the fire burning. Then he set down the brush. ‘No,’ he said quietly. ‘It feels wrong. Not yet.’ He re-wrapped the crown and put it back in his pack. Then one evening, while I was still wiping tears of laughter from my eyes at the end of a ribald song, the Fool set aside his harp and announced, ‘I must leave tomorrow.’

‘No!’ I protested in disbelief at his abruptness, and then ‘Why?’

‘Oh, you know,’ he replied airily. ‘It is the life of a White Prophet. I must be about predicting the future, saving the world – all those minor chores. Besides. You’ve run out of furniture for me to carve on.’