По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

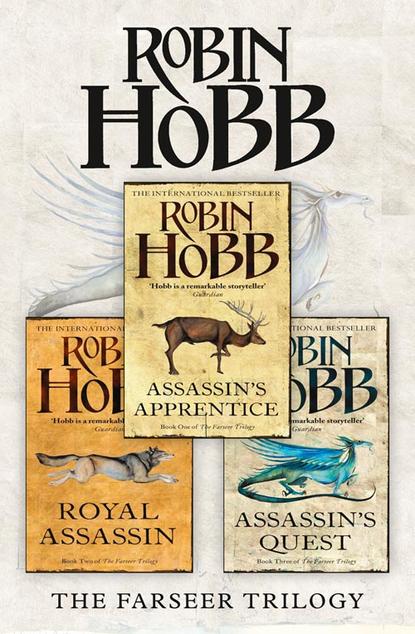

The Complete Farseer Trilogy: Assassin’s Apprentice, Royal Assassin, Assassin’s Quest

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The Trial (#ulink_12c5703f-3ea8-5a65-ad23-e8562abf4bd8)

The Man Ceremony is supposed to take place within the moon of a boy’s fourteenth birthday. Not all are honoured with it. It requires a Man to sponsor and name the candidate, and he must find a dozen other Men who concede the boy is worthy and ready. Living among the men-at-arms, I was aware of the ceremony, and knew enough of its gravity and selectivity that I never expected to participate in it. For one thing, no one knew my birth date. For another, I had no knowledge of who was a Man, let alone if twelve Men existed who would find me worthy.

But on a certain night, months after I had endured Galen’s test, I awoke to find my bed surrounded by robed and hooded figures. Within the dark hoods I glimpsed the masks of the Pillars.

No one may speak or write of the ceremony details. This, I think, I may say: as each life was put into my hands – fish, bird and beast – I chose to release it, not to death but back to its own free existence. So nothing died at my ceremony, and hence no one feasted. But even in my state of mind at that time, I felt there had been enough blood and death around me to last a lifetime, and I refused to kill with hands or teeth. My Man still chose to give me a name, so He could not have been totally displeased. The name is in the old tongue, which has no letters and cannot be written. Nor have I ever found any with which I chose to share the knowledge of my Man name. But its ancient meaning, I think, I can divulge here. Catalyst. The Changer.

I went straight to the stables, to Smithy and then to Sooty. The distress I felt at the thought of the morrow went from mental to physical, and I stood in Sooty’s stall, leaned my head against her withers, and felt queasy. Burrich found me there. I recognized his presence and the steady cadence of his boots as he came down the stable walkway, and then he halted abruptly outside Sooty’s stall. I felt him looking in at me.

‘Well. Now what?’ he demanded harshly, and I heard in his voice how weary he was both of me and my problems. Had I been any less miserable, my pride would have made me draw myself up and declare that nothing was wrong.

Instead, I muttered into Sooty’s coat, ‘Tomorrow Galen plans to test us.’

‘I know. He’s demanded quite abruptly that I furnish him horses for this idiotic scheme. I would have refused, had he not a wax signet from the King giving him authority. And no more do I know than that he wants the horses, so don’t ask it,’ he added gruffly as I looked up suddenly at him.

‘I wouldn’t,’ I told him sullenly. I would prove myself fairly to Galen, or not at all.

‘You’ve no chance of passing this trial he’s designed, have you?’ Burrich’s tone was casual, but I could hear how he braced himself to be disappointed by my answer.

‘None,’ I said flatly, and we were both silent a moment, listening to the finality of that word.

‘Well.’ He cleared his throat and gave his belt a hitch. ‘Then you’d best get it over with and get back here. It’s not as if you haven’t had good luck with your other schooling. A man can’t expect to succeed at everything he tries.’ He tried to make my failure at the Skill sound as if it were of no consequence.

‘I suppose not. Will you take care of Smithy for me while I’m gone?’

‘I will.’ He started to turn away, then turned back, almost reluctantly. ‘How much is that dog going to miss you?’

I heard his other question, but tried to avoid it. ‘I don’t know. I’ve had to leave him so much during these lessons, I’m afraid he won’t miss me at all.’

‘I doubt that,’ Burrich said ponderously. He turned away. ‘I doubt that a very great deal,’ he said as he walked off between the rows of stalls. And I knew that he knew, and was disgusted, not just that Smithy and I shared a bond, but that I refused to admit it.

‘As if admitting it were an option, with him,’ I muttered to Sooty. I bade my animals farewell, trying to convey to Smithy that several meals and nights would pass before he saw me again. He wriggled and fawned and protested that I must take him, that I would need him. He was too big to pick up and hug any more. I sat down and he came into my lap and I held him. He was so warm and solid, so near and real. For a moment I felt how right he was, that I would need him to be able to survive this failure. But I reminded myself that he would be here, waiting for me when I returned, and I promised him several days of my time for his sole benefit when I returned. I would take him on a long hunt, such as we had never had time for before. (Now) he suggested, and (soon) I promised. Then I went back up to the keep to pack a change of clothes and some travelling food.

The next morning had much of pomp and drama to it and very little sense, to my way of thinking. The others to be tested seemed enervated and elated. Of the eight of us who were setting out, I was the only one who seemed unimpressed by the restless horses and the eight covered litters. Galen lined us up and blindfolded us as three-score or more people looked on. Most of them were related to the students, or friends, or the keep gossips. Galen made a brief speech, ostensibly to us, but telling us what we already knew: that we were to be taken to different locations and left; that we must cooperate, using the Skill, in order to make our ways back to the keep; that if we succeeded, we would become a coterie and serve our king magnificently and be essential to defeating the Red Ship Raiders. The last bit impressed our onlookers, for I heard muttering tongues as I was escorted to my litter and assisted inside.

There passed a miserable day and a half for me. The litter swayed, and with no fresh air on my face or scenery to distract me, I soon felt queasy. The man guiding the horses had been sworn to silence and kept his word. We paused briefly that night. I was given a meagre meal, bread and cheese and water, and then I was reloaded and the jolting and swaying resumed.

At about midday of the following day, the litter halted. Once more I was assisted in dismounting. Not a word was said, and I stood, stiff and headachy and blindfolded in a strong wind. When I heard the horses leaving, I decided I had reached my destination and reached up to untie my blindfold. Galen had knotted it tightly and it took me a moment to get it off.

I stood on a grassy hillside. My escort was well on his way to a road that wound past the base of the hill, moving swiftly. The grass was tall around my knees, sere from winter, but green at the base. I could see other grassy hills with rocks poking out of their sides, and strips of woodland sheltering at their feet. I shrugged and turned to get my bearings. It was hilly country, but I could scent the sea and a low tide to the east somewhere. I had a nagging sense that the countryside was familiar; not that I had been to this particular spot before, but that the lie of the terrain was familiar somehow. I turned, and to the west saw the Sentinel. There was no mistaking the double-jag of its peak. I had copied a map for Fedwren less than a year ago, and the creator had chosen the Sentinel’s distinctive peak as a motif for the decorative border. So. The sea over there, the Sentinel there, and, with a suddenly dipping stomach, I knew where I was. Not too far from Forge.

I found myself turning quickly in a circle to survey the surrounding hillside, woodlands and road. No sign of anyone. I quested out, almost frantically, but found only birds and small game and one buck, who lifted his head and snuffed, wondering what I was. For a moment I felt reassured, until I remembered that the Forged ones I had encountered before had been transparent to that sense.

I moved down the hill to where several boulders jutted out from its side, and sat in their shelter. It was not that the wind was cold, for the day promised spring soon. It was to have something firmly against my back, and to feel that I was not such an outstanding target as I had been on top of the hill. I tried to think coolly what to do next. Galen had suggested to us that we should stay quietly where we were deposited, meditating and remaining open in our senses. At sometime in the next two days, he would try to contact me.

Nothing takes the heart out of a man more than the expectation of failure. I had no belief that he would really try to contact me, let alone that I would receive any clear impressions if he did. Nor did I have faith that the drop-off he had chosen for me was a safe location. Without much more thought than that, I rose, again surveyed the area for anyone watching me, then struck out toward the sea-smell. If I were where I supposed myself to be, from the shore I should be able to see Antler Island, and, on a clear day, possibly Scrim Isle. Even one of those would be enough to tell me how far from Forge I was.

As I hiked, I told myself I only wanted to see how long a walk I would have back to Buckkeep. Only a fool would imagine that the Forged ones still represented any danger. Surely winter had put an end to them, or left them too starved and weakened to be a menace to anyone. I gave no credence to the tales of them banding together as cut-throats and thieves. I wasn’t afraid. I merely wanted to see where I was. If Galen truly wanted to contact me, location should be no barrier. He had assured us innumerable times that it was the person he reached for, not the place. He could find me as well on the beach as he could on the hilltop.

By late afternoon, I stood on top of rocky cliffs, looking out to sea. Antler Island, and a haze that would be Scrim beyond it. I was north of Forge. The coast-road home would go right through the ruins of that town. It was not a comforting thought.

So now what?

By evening, I was back on my hilltop, scrunched down between two of the boulders. I had decided it was as good a place to wait as any. Despite my doubts, I would stay where I had been left until the contact time was up. I ate bread and salt-fish, and drank sparingly of my water. My change of clothes included an extra cloak. I wrapped myself in this and sternly rejected all thoughts of making a fire. However small, it would have been a beacon to anyone on the dirt road that passed the hill.

I don’t think there is anything more cruelly tedious than unremitting nervousness. I tried to meditate, to open myself up to Galen’s Skill, all the while shivering with cold and refusing to admit that I was scared. The child in me kept imagining dark, ragged figures creeping soundlessly up the hillside around me, Forged folk who would beat and kill me for the cloak I wore and the food in my bag. I had cut myself a stick as I made my way back to my hillside, and I gripped it in both hands, but it seemed a poor weapon. Sometimes I dozed despite my fears, but my dreams were always of Galen gloating over my failure as Forged ones closed in on me, and I always woke with a start, to peer wildly about to see if my nightmares were true.

I watched the sunrise through the trees, and then dozed fitfully through morning. Afternoon brought me a weary sort of peace. I amused myself by questing out toward the wildlife on the hillside. Mice and songbirds were little more than bright sparks of hunger in my mind, and rabbits little more, but a fox was full of lust to find a mate and further off a buck battered the velvet off his antlers as purposefully as any smith at his anvil. Evening was very long. It was surprising just how hard it was for me to accept, as night fell, that I had felt nothing, not the slightest pressure of the Skill. Either he hadn’t called or I hadn’t heard him. I ate bread and fish in the dark and told myself it didn’t matter. For a time, I tried to bolster myself with anger, but my despair was too clammy and dark a thing for anger’s flames to overcome. I felt sure Galen had cheated me, but I would never be able to prove it, not even to myself. I would always have to wonder if his contempt for me had been justified. In full darkness, I settled my back against a rock, my stick across my knees, and resolved to sleep.

My dreams were muddled and sour. Regal stood over me, and I was a child sleeping in straw again. He laughed and held a knife. Verity shrugged, and smiled apologetically at me. Chade turned aside from me, disappointed. Molly smiled at Jade, past me, forgetting I was there. Burrich held me by the shirt-front and shook me, telling me to behave like a man, not a beast. But I lay down on straw and an old shirt, chewing at a bone. The meat was very good, and I could think of nothing else.

I was very comfortable until someone opened a stable door and left it ajar. A nasty little wind came creeping across the stable floor to chill me, and I looked up with a growl. I smelled Burrich and ale. Burrich came slowly through the dark, with a muttered, ‘It’s all right, Smithy,’ as he passed me. I put my head down as he began to climb his stairs.

Suddenly there was a shout and men falling down the stairs. They struggled as they fell. I leaped to my feet, growling and barking. They landed half on top of me. A boot kicked at me, and I seized the leg above it in my teeth and clamped my jaws. I caught more boot and trouser than flesh, but he hissed in anger and pain, and struck at me.

A knife went into my side.

I set my teeth harder and held on, snarling around my mouthful. Other dogs had awakened and were barking, the horses were stamping in their stalls. Boy! Boy! I called for help. I felt him with me, but he didn’t come. The intruder kicked me, but I wouldn’t let go. Burrich lay in the straw and I smelled his blood. He did not move. I heard old Vixen flinging herself against the door upstairs, trying vainly to get to her master. Again and then again the knife plunged into me. I cried out to my Boy a last time, and then I could no longer hold on. I was flung off the kicking leg, to strike the side of a stall. I was drowning, blood in my mouth and nostrils. Running feet. Pain in the dark. I hitched closer to Burrich. I pushed my nose under his hand. He did not move. Voices and light coming, coming, coming …

I awoke on a dark hillside, gripping my stick so tightly my hands were numb. Not for a moment did I think it a dream. I couldn’t stop feeling the knife between my ribs, and tasting the blood in my mouth. Like the refrain of a ghastly song, the memories came again and again, the draught of cold air, the knife, the boot, the taste of my enemy’s blood in my mouth, and the taste of my own. I struggled to make sense of what Smithy had seen. Someone had been at the top of Burrich’s stairs, waiting for him. Someone with a knife. And Burrich had fallen, and Smithy had smelled blood …

I stood and gathered my things. Thin and faint was Smithy’s warm little presence in my mind. Weak, but there. I quested carefully, and then stopped when I felt how much it cost him to acknowledge me. Still. Be still. I’m coming. I was cold and my knees shook beneath me, but sweat was slick on my back. Not once did I question what I must do. I strode down the hill to the dirt road. It was a little trade road, a pedlars’ track, and I knew that if I followed it, it must intersect eventually with the coast-road. I would follow it, I would find the coast-road, I would get myself home. And if Eda favoured me, I would be in time to help Smithy. And Burrich.

I strode, refusing to let myself run. A steady march would carry me further faster than a mad sprint through the dark. The night was clear, the trail straight. I considered, once, that I was putting an end to any chance of proving I could Skill. All I had put into it – time, effort, pain – all wasted. But there was no way I could have sat down and waited another full day for Galen to try and reach me. To open my mind to Galen’s possible Skill touch, I would have had to clear it of Smithy’s tenuous thread. I would not. When it was all put in the balances, the Skill was far outweighed by Smithy. And Burrich.

Why Burrich, I wondered. Who could hate him enough to ambush him? And right outside his own quarters. As clearly as if I were reporting to Chade, I began to assemble my facts. Someone who knew him well enough to know where he lived; that ruled out some chance offence committed in a Buckkeep town tavern. Someone who had brought a knife; that ruled out someone who just wanted to give him a beating. The knife had been sharp, and the wielder had known how to use it. I winced again from the memory.

Those were the facts. Cautiously, I began to build assumptions upon them. Someone who knew Burrich’s habits and had a serious grievance against him, serious enough to kill over. My steps slowed suddenly. Why hadn’t Smithy been aware of the man up there waiting? Why hadn’t Vixen been barking through the door? Slipping past dogs in their own territory bespoke someone well practised at stealth.

Galen.

No. I only wanted it to be Galen. I refused to leap to the conclusion. Physically, Galen was no match for Burrich and he knew it. Not even with a knife, in the dark, with Burrich half-drunk and surprised. No. Galen might want to, but he wouldn’t do it. Not himself.

Would he send another? I pondered it, and decided I didn’t know. Think some more. Burrich was not a patient man. Galen was the most recent enemy he’d made, but not the only one. Over and over I re-stacked my facts, trying to reach a solid conclusion. But there simply wasn’t enough to build on.

Eventually I came to a stream, and drank sparingly. Then I walked again. The woods grew thicker, and the moon was mostly obscured by the trees lining the road. I didn’t turn back. I pushed on, until my trail flowed into the coast-road like a stream feeding a river. I followed it south, and the wider highway gleamed like silver in the moonlight.

I walked and pondered the night away. As the first creeping tendrils of dawn began to put colour back into the landscape, I felt incredibly weary, but no less driven. My worry was a burden I couldn’t put down. I clutched at the thin thread of warmth that told me Smithy was still alive, and wondered about Burrich. I had no way of knowing how badly he’d been injured. Smithy had smelled his blood, so the knife had scored at least once. And the fall down the staircase? I tried to set the worry aside. I had never considered that Burrich could be injured in such a way, let alone what I would feel about it. I could come up with no name for the feeling. Just hollow, I thought to myself. Hollow. And weary.

I ate a bit as I walked and refilled my waterskin from a stream. Midmorning clouded up and rained on me for a bit, only to clear as abruptly by early afternoon. I strode on. I had expected to find some sort of traffic on the coast-road, but saw nothing. By late afternoon, the road had veered close to the cliffs. I could look across a small cove and down onto what had been Forge. The peacefulness of it was chilling. No smoke rose from the cottages, no boats rode in the harbour. I knew my route would take me right through it. I did not relish the idea, but the warm thread of Smithy’s life tugged me on.

I lifted my head to the scuff of feet against stone. Only the reflexes of Hod’s long training saved me. I came about, staff at the ready, and swept around me in a defensive circle that cracked the jaw of the one that was behind me. The others fell back. Three others. All Forged, empty as stone. The one I had struck was rolling and yelling on the ground. No one paid him any mind except me. I dealt him another quick jolt to his back. He yelled louder and thrashed about. Even in that situation, my action surprised me. I knew it was wise to make sure a disabled enemy stayed disabled, but I knew I could never have kicked at a howling dog as I did at that man. But fighting these Forged ones was like fighting ghosts: I felt no presence from any of them; I had no sense of the pain I’d dealt the injured man, no echoes of his anger or fear. It was like slamming a door, violence without a victim, as I cracked him again, to be sure he would not snatch at me as I leaped over him to a clear space in the road.

I danced my staff around me, keeping the others at bay. They looked ragged and hungry, but I still felt they could outrun me if I fled. I was already tired, and they were like starving wolves. They’d pursue me until I dropped. One reached too close and I struck him a glancing blow to the wrist. He dropped a rusty fish-knife and clutched his hand to his heart, shrieking over it. Again, the other two paid no attention to the injured one. I danced back.

‘What do you want?’ I demanded of them.

‘What do you have,’ one of them said. His voice was rusty and hesitant, as if long unused, and his words lacked any inflection. He moved slowly around me, in a wide circle that kept me turning. Dead men talking, I thought to myself, and couldn’t stop the thought from echoing through my mind.