По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

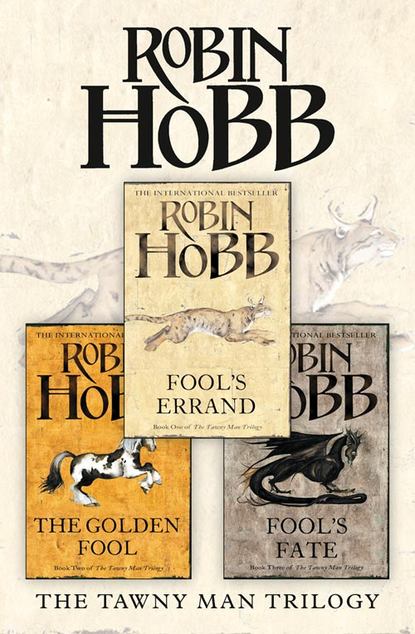

The Complete Tawny Man Trilogy: Fool’s Errand, The Golden Fool, Fool’s Fate

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

That’s true, I agreed, but I wondered at the slight sinking of my heart at the thought. Didn’t I want to leave Buckkeep and resume my own life as soon as possible? Or was I coming to relish my role as a serving-man to a wealthy fop? I asked myself sarcastically.

I took Lord Golden’s coat for him, and then eased him from his boots. As I had so often seen Charim do without paying any heed, I brushed and hung the jacket, and gave the boots a hasty dusting before setting them aside. When Lord Golden offered me his wrists, I undid the fastenings of the lacy cuffs of his shirt and set the glittering gauds aside. He leaned back in his chair. ‘I shall wear my blue doublet tonight. And the linen shirt with the fine blue stripe in it. Dark blue hose, I think, and the shoes with the trimming of silver chain. Lay it all out for me. Then pour the buckets, Badgerlock, and be generous with the rose oil. Then set the screens and leave me to my thoughts for a bit. Oh, and please, take some of this water into your chambers and avail yourself of it. When we dine, I shall want to smell the food, not you standing behind me. Oh. And wear the dark blue tonight. I think it will set off my own garb the better. One other thing. Put this on as well, but I counsel you to keep it covered unless you truly need it.’

From his pocket he drew forth Jinna’s charm. It coiled into my extended hand.

All this he announced with an air of genial good cheer. Lord Golden was a man well pleased with himself, looking forwards to an evening of pleasant talk and hearty viands. I did as I was bid, and then gratefully retreated to my own room with washwater and a bit of apple-scented oil. Shortly I heard Lord Golden splashing luxuriously whilst humming a tune I did not know. My own washing was a bit more restrained but just as welcome to me. I hurried, knowing that my services would soon be required again.

I struggled with my doublet, finding that it had been tailored far more close-fitting than I was accustomed to. There was scarcely room to conceal Chade’s roll of tools let alone the small knife that I decided I would carry. I could scarcely wear a sword into the dining room on a social occasion, but I found I did not wish to go completely unarmed. The wolf’s secretive approach to the Wit tonight had infected me with wariness. I cinched the belt that secured the doublet and then pulled my hair back into its warrior tail. Some of the apple-scented oil persuaded my hair to lie flatter. I realized I had not heard splashing for some moments, and hastened back into Lord Golden’s chamber.

‘Lord Golden, do you require my assistance?’

‘Scarcely.’ A shadow of the Fool was in Golden’s drawled sarcasm. He emerged from behind the screen, fully dressed, and adjusting the fall of lace at his cuffs. A small smile of pleasure at surprising me was playing about his mouth as he lifted his eyes to me. Abruptly, the smile faded. For a time he simply stared at me, mouth slightly ajar. Then his eyes lit. As he advanced to me, satisfaction shone in his face. ‘It’s perfect,’ he breathed. ‘Exactly as I had hoped. Oh, Fitz, I always imagined that, had I the chance, I could show you off as befitted you. And look at you.’

His use of my name was as astonishing as the way he gripped my shoulders and propelled me towards the immense mirror. For a moment I looked only at the reflection of his face over my shoulder, alight with pride and satisfaction. Then I shifted my gaze and stared at a man I scarcely recognized.

His directions to the tailor must have been very complete. The doublet encased my shoulders and chest. The white of the shirt showed at the collar and the sleeves. The blue of the doublet was Buck blue, my family colour, and even if I now wore it as a servant, the cut of the doublet was not that of servant but of soldier. The tailoring made my shoulders look broad and my belly flat. The white of the shirt contrasted with my dark skin and eyes and hair. I gazed at my own face in consternation. The sharpness of my scars had faded with my youth. There were lines on my brow and starting at the corners of my eyes, and somehow these lessened the severity of the scar’s passage down my face. I had long ago accepted the modification of my broken nose. The streak of white in my hair was more noticeable with my hair drawn back in a warrior’s tail. The man that looked back at me from the mirror put me somewhat in mind of Verity, but even more of the portrait of King-in-Waiting Chivalry that still hung in the hall at Buckkeep.

‘I look like my father,’ I said quietly. The prospect of that both pleased and alarmed me.

‘Only to someone seeking that resemblance,’ the Fool replied. ‘Only someone knowing enough to peer past your scars would see the Farseer in you. Mostly, my friend, you look like yourself, only more so. You look like the FitzChivalry that was always there, but kept hidden by Chade’s wisdom and subterfuge. Did you never wonder at how your clothes were cut, simply and almost rough, to make you look more stablehand and soldier than prince’s bastard? Mistress Hasty the seamstress always thought the orders came from Shrewd. Even when she was allowed to indulge in her fripperies and fashion, it was only the ones that drew attention to themselves and her sewing skills and away from you. But this, Fitz, this is how I have always seen you. And how you have never seen yourself.’

I looked back at the glass. I think I speak truth when I say that I have never been a vain man. It took a moment for me to accept that, while I had aged, the change was one of maturity rather than of degeneration. ‘I don’t look that bad,’ I conceded.

The Fool’s smile went broader. ‘Ah, my friend, I have been places where women would have fought one another with knives over you.’ He lifted a slender hand and rubbed his chin thoughtfully. ‘And now, I fear I must wonder if my fancy has succeeded too well. You will not pass without remark. But perhaps that is for the best. Flirt a bit with the kitchen maids, and who knows what they will tell you?’

I rolled my eyes at his mockery. His gaze met mine in the mirror. ‘Nothing finer than we two has dined in these halls before,’ he decided emphatically. He squeezed my shoulder, and then stood straight, abruptly Lord Golden again.

‘Badgerlock. The door. We are expected.’

I jumped to obey my master. Somehow, those few moments with the Fool had restored my tolerance for this new charade of ours. I even found my interest warming to it. If Prince Dutiful were here at Galeton, as I suspected he was, we would find him out before the night was through. Lord Golden preceded me through the door and I followed two steps behind him and to his left.

SIXTEEN Claws (#ulink_c4d9b9c5-8ad3-5b72-80e1-7a255d6f6f43)

The depredations of the Red Ship War took their heaviest tolls on the Coastal Duchies. Old fortunes were decimated, family lines failed, and once-proud holdings were reduced to ashy ruins and weedy courtyards. Yet in the wake of the war, just as seedlings sprout in the spring after a lightning fire, so too did many of the minor nobility find their fortunes swelling. Many of the humbler holdings had escaped the raiders’ attention. Flocks and crops survived, and what would once have seemed a secondary property came to be seen as places of plenty. The lesser lords and ladies of these lands suddenly found themselves seen as desirable matches for the heirs of older but suddenly less wealthy family lines. Thus the widowed lord of the Bresinga holdings near Galeton took a much younger and wealthier bride from amongst the Earwood family of Lesser Tor in Buck. The Earwood family was an old and noble line that had dwindled in both standing and wealth. Yet in the years of the Red Ship War, their sheltered valley prospered and shared harvest with the devastated folk of the Bresinga holdings that bordered them. This kindness bore fruit for the Earwood family when Jaglea Earwood became Lady Bresinga. She bore to her elderly lord an heir, Civil Bresinga, shortly before his death from a fever.

Scribe Duvlen’s A History of the Earwood Line

Lord Golden moved with the grace and certainty that is supposedly bone-bred in the nobility. Unerringly he led me to an elegant antechamber where his hostess and her son awaited him. Laurel was there, attired in a simple gown of soft cream trimmed with lace. She was deep in conversation with the Bresinga Huntsman. I thought that the gown did not suit her as well as her simple tunic and riding breeches had, for her tanned arms and face seemed to make the dainty lace at the collar and belled sleeves incongruous on her. Lady Bresinga was elaborately flounced and draped for dinner, the abundance of her garments swelling the proportions of her bust and hips. There were three other guests: a married couple and their daughter of about seventeen, obviously local gentry. All had been waiting for Lord Golden.

Their reaction when we entered was everything the Fool had claimed it would be. Lady Bresinga turned to greet her guest, smiling. Her eyes swept over him, widening with pleasure. ‘Our honoured guest is here,’ she announced. Lord Golden turned his head slightly to one side, tucking his chin in with an innocent air as if he were unaware of his own beauty. Laurel stared at him in frank admiration as Lady Bresinga introduced Lord Golden to Lord and Lady Grayling of Cotterhills and their daughter Sydel. Their names were unfamiliar but I seemed to recall Cotterhills as a tiny holding in the foothills of Farrow. Sydel’s cheeks grew pink and she appeared almost flustered at being included in Lord Golden’s bow, and after that, the young gentlewoman’s gaze appeared fixed on him. Her mother’s eyes had wandered over to me and were frankly appraising me in a way that should have made her blush. I glanced away only to find Laurel looking at me with a bemused smile, as if she had forgotten she knew me. I could almost feel Lord Golden’s radiant satisfaction in how he had turned their heads.

He offered his arm to Lady Bresinga, and her son Civil escorted Sydel. Lord and Lady Grayling followed and then came the Huntmasters. I followed my betters into the dining room and took up my post behind Lord Golden’s chair. My position proclaimed me bodyguard as well as servant. Lady Bresinga glanced at me questioningly but I did not meet her eyes. If she thought that Lord Golden had breached her hospitality by having me accompany him, she did not comment on it. Young Civil simply stared for a moment or two, and then shrugged off my presence with a quiet aside to his companion. And after that, I became invisible.

I think it was the most curious vantage point I’d ever held in my spying career. It was not comfortable. I was hungry, and Lady Bresinga’s board was loaded with dishes both savoury and sweet. The servants who brought and cleared away the repast passed right before me. I was also weary and aching from the long day’s ride, yet I forced myself to stand as still as possible, with no restless shifting, and to keep my eyes and my ears open.

All the talk at the table had to do with game and hunting. Lord Grayling and his lady and daughter were avid hunters, and evidently had been invited for this reason. Almost immediately, another common thread emerged. They hunted, not with hounds, but with cats. Lord Golden professed himself a complete novice at this sort of sport and begged them to enlighten him. They were only too pleased to do so, and the conversation soon bogged down into intricate arguments as to which breed of hunting cat did better on birds, with various tales exchanged to illustrate the different breeds’ prowess. The Bresingas were vocal in support of a short-tailed breed called ealynex, while Lord Grayling vociferously offered heavy wagers that his gruepards would take the day regardless of whether they sought birds or hares.

Lord Golden was a most flattering listener, asking avid questions and expressing amazement and fascination at the replies. The cats, he learned for both of us, were not coursing beasts, at least not in the same manner as hounds. Each hunter took a single feline, and it rode to the hunt on a special cushion, secured just behind its master’s saddle. The larger gruepards could be loosed against game up to the size of young deer. They relied on a burst of speed to catch their prey, and then suffocated it to death with a throat hold. The smaller ealynex was more often set loose in tall grassy meadows or underbrush, where it stalked its prey until it could leap upon it. It preferred to stun with a blow from a swift paw, or to break the neck or back with a single bite. It was sport, we learned, to loose such beasts upon a flock of tame pigeons or doves, to see how many they could bat to the ground before the whole flock took flight. Often these smaller, bob-tailed cats were matched against one another in bird batting competitions, with sizeable wagers riding on the favourites. The Bresingas boasted no less than twenty-two cats of both types in their hunting stables. The Graylings had only the gruepards, and but six of them in their clowder, but Lady Bresinga assured Lord Golden that her friend was fortunate in possessing some of the best breeding lines she had ever seen.

‘Then they are bred, these hunting cats? I was told that they had to be captured, that they would not breed if tamed.’ Lord Golden fastened his attention on the Bresingas’ Huntmaster.

‘Oh, the gruepards will breed, but only if they are allowed to carry out their mating battles and harsh courtship without interference. The enclosure Lord Grayling has devoted to this purpose is quite large, and no human must ever enter it. We are quite fortunate that his efforts in that regard have been successful. Prior to this, as you perhaps know, all gruepards were brought in from either Chalced or the Sandsedge regions of Farrow, all at great expense, of course. They were quite rare in this area when I was a boy, but the moment I saw one, I knew that was the hunting beast for me. And I hope I don’t sound a braggart in saying that, since the gruepards were so expensive, I was one of the first who thought of trying to tame our native ealynex to the same task. Hunting with the ealynex was quite unknown in Buck until my uncle and I first caught two of them. The ealynex are the cats that must be taken as adults, usually in pit-traps, and schooled to hunt as companions.’ This all spouted from the Bresinga Huntsman, a tall fellow who hunched forwards earnestly as he spoke. Avoin was his name. The topic was plainly his passion.

Lord Golden flattered him with his unwavering attention. ‘Fascinating. I must hear how such deadly little creatures are brought to heel. Nor was I aware there were so many names for hunting cats. I had assumed there was but one breed. So. Let me see. I was told that Prince Dutiful’s hunting animal had to be taken from the den as a kitten. It must be a gruepard, then?’

Avoin exchanged a glance with his mistress, almost as if he asked permission before he spoke. ‘Ah, well. The Prince’s cat is neither ealynex nor gruepard, Lord Golden. It is a rarer creature than either of those. Most know it as the mistcat. It ranges much higher into the mountains than our cats do, and is known for hunting amid the branches of the trees as well as on the ground.’ Avoin had dropped into the lecturing tone of the expert. Once he had begun to share his expertise, he would continue until his listeners’ eyes glazed over. ‘For its size, it takes game substantially larger than itself, dropping down on both deer and wild goats to either ride them to exhaustion, or to break the neck with a bite. On the ground, it is neither as swift as the gruepard nor as stealthy as the ealynex, but combines the techniques of both with good success against small game. But of the mistcat, you heard true. It must be taken from its home den before its eyes are opened if it is to be tamed at all. Even then, it may have an uneven temperament, but those who are taken and trained correctly become the truest companions that any hunter could desire. They will only hunt for one master, however. Of mistcats it is said, “from the den to the heart, never to part”. Meaning, of course that only he who is sly enough to find the mistcat’s den will ever possess one. It is quite a feat, to have a mistcat. When you see a hunter with a mistcat, you know you’re seeing a master of cat-hunting.’

Avoin’s voice suddenly faltered. If some sign had passed between him and his mistress, I had not seen it. Was the Huntsman involved then, in the circumstances that had brought such a cat to the Prince?

Lord Golden, however, blithely ignored the implications of what he had heard. ‘A sumptuous gift for our prince indeed,’ he enthused. ‘But it quite dashes my hopes of having a mistcat as my hunting creature tomorrow. At least, shall I have the prospect of seeing one set loose?’

‘I fear not, Lord Golden,’ Lady Bresinga replied graciously. ‘We have none in our hunting pack. They are quite rare. To see a mistcat hunt, you will have to ask the Prince himself to take you along on one of his outings. I am sure he would be delighted to do so.’

Lord Golden shook his head merrily, tucking his chin in as if taken aback. ‘Oh, no, dear lady, for I have heard that our illustrious prince hunts afoot with his cat, at night, regardless of the weather. Much too physical an endeavour for me, I fear. Not at all to my taste, not at all!’ Chuckles tumbled from him like spinning pins in a juggler’s hands. All around the table, the others joined in his mirth.

Climb.

I felt the prickle of tiny claws and glanced down. From somewhere, a small striped kitten had materialized. She stood on her hind legs, her front feet securely attached to my leggings by her embedded claws. Her yellow-green eyes looked up earnestly at mine. Coming up!

I refused the touch of her mind without, I hoped, seeming to. At the table, Lord Golden had led the conversation to what types of cats they might use tomorrow, and whether or not they would damage the plumage on the game. Feathers, he reminded them all, were what he sought, though he did enjoy gamebird pie.

I shifted my foot, hoping to dislodge the young bramble-foot. It did not work. Climbing! she insisted, and hopped up another notch. Now she hung from me by all four paws, her claws having penetrated my leggings to hook in my flesh. I reacted, I hoped, as any other servant might. I winced and then unobtrusively bent to pry the creature free, one thorny foot at a time. My action might have escaped attention if she had not mewled piteously at being thus thwarted. I had hoped to set her gently back on the floor, but Lord Golden’s amused voice with, ‘Well, Badgerlock, and what have you caught?’ directed all eyes to me.

‘Just a kitten, sir. She seemed determined to climb my leg.’ She was like a puff of dandelion fuzz in my hand. The deceptive depth of her fluffy coat was belied by the tiny ribcage in my hand. She opened her little red mouth and miaowed for her mother.

‘Oh, there you are!’ Lord Grayling’s daughter exclaimed, leaping up from the table. Heedless of any decorum, Sydel rushed to take the squirming kitten from my hand. With both hands she cradled the kitten under her chin. ‘Oh, thank you for finding her.’ She walked back to her place at the table, speaking as she went. ‘I could not bear to leave her alone at home, and yet she must have slipped out of my room just after breakfast, for I haven’t seen her all day.’

‘And is this, then, the kit of a hunting cat?’ Lord Golden asked as the daughter seated herself.

Sydel leapt at the chance to address Lord Golden. ‘Oh, no, Lord Golden, this is my own sweet pet, my little pillow-cat, Tibbits. She is such a mischief, aren’t you, lovey? And yet I cannot bear to be parted from her. How you have worried me this afternoon!’ She kissed the kitten on the top of her head and then settled the creature in her lap. No one at table seemed to regard her behaviour as unusual. As the meal and conversation resumed, I saw the little tabby head pop up at the edge of the table. Fish! The kit thought delightedly. A few moments later, Civil offered her a sliver of fish. I decided it meant little; it could be coincidence, or even the unconscious reaction that those without the Wit sometimes make to the wishes of animals they know well. The kit swiped a paw to claim possession of the morsel, and then took it into her owner’s lap to devour it.

Servants entered the hall to clear dishes and platters away, while a second rank of servants followed with sweet dishes and berry wines. Lord Golden had seized control of all conversation. The hunting tales he told were either fabulous concoctions or indicated that his life during the last ten years or so had been far different from what I had imagined. When he spoke of spearing sea-mammals from a skinboat drawn by harnessed dolphins, even Sydel looked slightly incredulous. But as is ever the case, if a story is well told, the listeners will stay with it to the end, and so they did this time. Lord Golden finished his recital with a flourish and a wicked gleam in his eye that suggested that if he were embellishing his adventure, he would never admit it.

Lady Bresinga called for brandy to be brought, and the table was cleared again. The brandy appeared with yet another assortment of small items to tempt already-satiated guests. Eyes went from sparkling with wine and merriment to the deep gleam of contentment that good brandy brings forth after a fine meal. My legs and lower back ached abominably. I was hungry as well, and tired enough that if I had been free to lie down on the flagged floor, I would instantly have been asleep. I scraped my nails against the inside of my palms, pricking myself back to alertness. This was the hour when tongues were loosest and talk most expansive. Despite the way Lord Golden leaned back in his chair, I doubted that he was as intoxicated as he seemed. The subject had rounded back to cats and hunting again. I felt I had learned as much as I needed to know about the topic.

The kitten had managed, after six thwarted efforts, to gain the top of the table. She had curled up and briefly napped, but now was wending her way amongst the bottles and glasses, threatening to topple them as she rubbed against each. Mine. And mine. This is mine, too. And mine. With the total confidence of the very young, she claimed every item on the table as her own. When Civil reached for the brandy snifter to refill his glass and that of his companion, the kitten arched her little back and bounced towards him on her toes, intent on making good on her claims. Mine!

‘No. Mine,’ he told her affably, and fended her off with the back of his wrist. Sydel laughed at the exchange. A slow excitement uncoiled within me but I kept my dulled stare apparently fixed on my master’s shoulder. Witted. Both of them. I was sure of it now. And as it tended to be inherited in families …

‘So. Who did catch the mistcat for the Prince’s gift?’ Lord Golden suddenly asked. The question almost followed from the conversation, yet it was pointed enough to turn all heads at the table. Lord Golden gave a small hiccup that bordered on being a discreet belch. It was enough of a distraction to combine with his slightly goggled stare to take the edge from his query. ‘I’ll wager it was you, Huntsman.’ His graceful hand made his words a compliment to Avoin.

‘No, not I,’ Avoin shook his head but oddly volunteered no more information.

Lord Golden leaned back, tapping his forefinger on his lips as if it were a guessing game. He rolled his gaze about the table, then chortled sagely and pointed at Civil. ‘Then it was you, young man. For I heard it was you who carried the cat up to Prince Dutiful to present him.’

The boy’s eyes flickered once to his mother’s before he gravely shook his head. ‘Not I, Lord Golden,’ he demurred. And again, that unusual silence of information withheld followed his words. A united front, I decided. The question would not be answered.

Lord Golden lolled his head back against his chair, and took a long noisy breath and sighed it out. ‘Damned fine gift,’ he observed liberally. ‘Love to have one myself, from all I’ve heard. But hearing’s no substitute for seeing. B’lieve I will ask Prince Dutiful to allow me to ’ccompany him some night.’ He sighed again and let his head wag to one side. ‘If he ever comes back from his meditation retreat. Not natural, if you ask me, for a boy that age to spend so much time alone. Not natural a’tall.’ Lord Golden’s enunciation was giving way rapidly.