По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

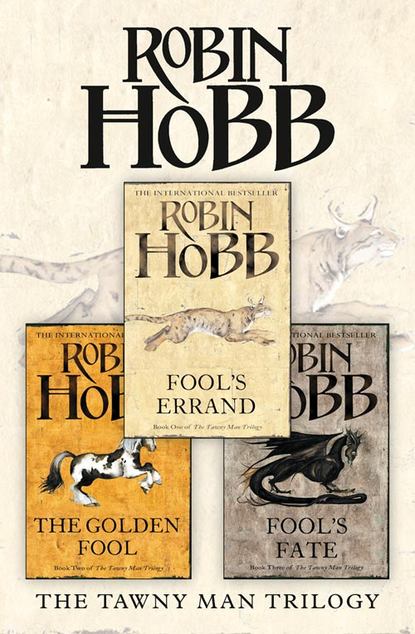

The Complete Tawny Man Trilogy: Fool’s Errand, The Golden Fool, Fool’s Fate

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She shrugged one shoulder and smiled, but I think the intensity of my question made her uneasy. ‘There are lots of tales, but most have the same spine.’ She drew a breath. ‘A straying child or an idle shepherd or lovers who have run away from forbidding parents come to the mounds. In most tales they sit down beside them to rest, or to find a bit of shade on a hot day. Then the ghosts rise from the mounds, and lead them to the standing stone. And they follow the ghost inside, to a different world. Some say they never come back. Some say they come back aged and old after being gone but a night, but others say the opposite: that a hundred years later, the lovers came back, hand in hand, as young as ever, to find their quarrelling parents long dead and that they are free to wed.’

I had my own opinion of such tales, but did not voice them. Once I had stepped through such a pillar, to find myself in a distant dead city. Once the black stone walls of that long-dead city had spoken to me, and the city had sprung to life around me. Monoliths and cities of black stone were the work of the Elderlings, long perished from the world. I had believed the Elderlings had been denizens of a far realm, deep in the mountains behind Kettricken’s Mountain Kingdom. Twice now I had seen evidence that they had walked these Six Duchies hills as well. But how many summers ago?

I tried to catch Lord Golden’s eye, but he stared straight ahead and it seemed to me that he hastened his horse on. I knew by the set of his mouth that any question I asked him would be answered with another question or with an evasion. I focused my efforts on Laurel.

‘It seems odd that you would hear tales of this place in Farrow.’

She gave that small shrug again. ‘The tales I heard were of a similar place in Farrow. And I told you. My mother’s family came from a place not far from the Bresinga holdings. We often visited, when she was still alive. But I’d wager that the folk around here tell the same sort of tales about those mounds and that pillar. If any folk do live around here.’

That seemed unlikely as the day wore on. The further we rode on, the wilder the country became. The horizon darkened and the storm muttered threats but came no nearer. If these valleys had ever known the plough, or these hills ever nurtured pasturing kine, they had forgotten it these many years. The earth was dry, stones thrusting out amongst the clots of dried up grasses and scrubby brush. Chirring insects and birdcalls were the only signs of animal life. The trail became more difficult to follow and perforce we went more slowly. Often I glanced back behind us. Our tracks on top of the tracks we followed would make it easier for our pursuers to catch up with us, but I could think of no alternative.

The constant hum of the insects suddenly hushed off to our left. I turned towards it, my heart in my mouth, but an instant later I felt my brother’s presence. Two breaths, and I could see him. As always I marvelled at how well the wolf could hide himself even in the scantiest of cover. As he drew closer, my gladness at seeing him turned to dismay. He trotted determinedly, head down, and his tongue hung nearly to his knees. Without a word to the others, I pulled up Myblack and dismounted, taking down my waterskin. He came to me, to drink water from my cupped hands.

How did you catch up so swiftly?

You follow tracks, going slowly to find your way. I followed my heart. Where your path has wound through these hills, mine brought me straight to you, over terrain a horse would not relish.

Oh, my brother.

No time to pity me. I came to bring you warning. You are followed. I passed those who come behind you. They stopped at the bodies. They were enraged, shouting to the skies. Their anger will delay them for a time, but when they come on, they will ride fast and furious.

Can you keep up?

I can hide, far more easily than you can. Instead of thinking of what I will do, you should think of what you should do.

There was little enough we could do. I remounted, kicked Myblack and caught up with the others. ‘We should try for more speed.’

Laurel gave me a look, but said nothing. Only a shift in Lord Golden’s posture betrayed he had heard me, but in answer Malta sprang forwards. Myblack suddenly decided she would not be outdone. She leapt forwards, and in four strides we led the way. I kept my eyes on the ground as we hurried along. It looked as if the Prince and his fellows had made for the shelter of some trees; I applauded their decision. I looked forwards to gaining the cover. I urged a bit more speed from Myblack and led us all directly into the ambush.

A mental shout from Nighteyes prompted me to rein to one side. Laurel took the arrow, dropping to the earth with a cry. The shot had been intended for me. Fury and horror blazed up in me and I rode Myblack straight at the stand of trees. My luck was that there was only one archer, and he had not had time to nock another arrow. As we passed under the downsweeping branches, I stood up in my stirrups, miraculously caught a firm hold and pulled myself up on the branch. The archer was trying to swing his arm to bring the arrow to bear on me, but the intervening small branches were hampering him. There was no time to think about consequences. I launched myself at him, springing like a wolf. We fell in a tangle of two men and the bow. A projecting branch nearly broke my shoulder without breaking our fall. It turned us in the air. We landed with the young archer on top of me.

The impact slammed the air out of me. I could think but not act. Nighteyes saved me the need. He dashed in, a rush of claws and teeth that swept the youth off my body. I felt our attacker’s surprised attempt at a repel against Nighteyes. I think he was too shocked to put much strength into it. I lay on the earth as they fought beside me, trying frantically to pull air into my lungs. He swung a fist but Nighteyes dodged and seized his passing wrist. The archer shrieked and launched a wild kick at the wolf. I felt its stunning impact. Nighteyes kept his hold but lost the strength in it. As the man wrenched his torn wrist from the wolf’s jaws, I found enough breath to act.

From where I lay, I kicked the archer in the head. I flung myself on top of the man. My hands found his throat as Nighteyes seized his right calf in his jaws and hung on. The man flopped wildly between us but could not escape. Nighteyes worried his leg. I squeezed his throat and held on until I felt his struggles cease. Even then, I kept a grip on his throat with one hand as my other found my belt knife. The entire world had shrunk to a reddened circle that was my vision of his face.

‘… kill him! Don’t kill him! Don’t kill him!’

Lord Golden’s shouts penetrated my mind finally as I held the knife to our attacker’s throat. I had never been less inclined to listen. Yet as the red haze of battle faded from my vision, I found myself looking down at a boy little older than Hap. His blue eyes stood out in their sockets, both in horror of death and for lack of air. Something in our fall had scraped the side of his face and blood stood out in fine rows on his cheek. I loosened my grip and Nighteyes dropped his leg. But still I straddled his chest and held my knife to his throat. I was not at all sentimental as to the innocence of young boys. We’d already seen this one’s bow-work. He would as soon kill me as not. I kept my gaze on him as I asked the Fool, ‘Is Laurel dead?’

‘Scarcely!’ The incensed voice was female. Laurel staggered over to us. A glance showed me her hand clamped tight to the point of her shoulder. Blood was leaking through her fingers. She had already pulled the arrow out.

‘Did you get the head out?’ I asked quickly.

‘I would not have pulled it out if I hadn’t been sure I could get the whole thing,’ she replied waspishly. Pain did not improve her temperament. She was pale but two bright spots of colour stood on her cheeks. She looked down at the boy I straddled and her eyes went very wide. I heard her take a ragged breath.

Nighteyes stood beside me, panting heavily. We should get out of here. The thought was sluggish with pain. Others may come. Those who follow or those who went ahead. I saw the boy’s brow furrow.

I glanced at Laurel. ‘Can you ride as you are? Because we must leave here. We need to question him, but this isn’t the time. We don’t want to be caught by those who follow, or by his friends coming back for him.’

I could tell by her eyes that she didn’t know the answer to my question but she lied bravely. ‘I can ride. Let’s go. I, too, have questions I’d like to ask this one.’ The archer stared at her, horror-stricken at the venom in her voice. He suddenly bucked under me, trying to escape. I backhanded him with my free hand. ‘Don’t try that again. It’s much easier for me to kill you than drag you along.’

He knew I spoke truth. His eyes went to Lord Golden and then to Laurel before his gaze came back to me. He peered up at me, blood leaking from his nose and I recognized his shocked look. This was a young man who had killed, but never before been in imminent danger of being killed. I felt oddly qualified to introduce him to the sensation. No doubt I had once worn that same expression.

‘On your feet.’ Fifteen years ago, I would have backed up the command by hauling him upright. Now I kept a grip on his shirt front but let him stand up himself. I was short of breath after our tussle, and not inclined to spend my reserves on a show of strength. Nighteyes lay down on the moss beneath the tree, unabashedly panting.

Disappear, I suggested to him.

In a moment.

The archer stared from me to my wolf and back again, confusion growing in his eyes. I refused to meet his gaze. Instead, I cut the leather thong that fastened the collar of his shirt. He flinched as my knife blade tugged through it. I jerked the leather loose, and roughly turned him. ‘Your hands,’ I demanded, and without quibbling, he put them behind him. The fight seemed to have gone out of him. The teethmarks in his arm were still bleeding. I tied his wrists tightly together. I completed my task and glanced up to find Laurel glowering at my prisoner. Obviously, she was taking the attack personally. Perhaps no one had ever tried to kill her before. The first time is always a memorable experience.

Lord Golden assisted Laurel into the saddle. I knew she wanted to refuse his help, but didn’t dare. Missing her mount would be more humiliating than accepting his support. That left Myblack to carry my captive and me. Neither my horse nor I were happy with it. I picked up the archer’s bow, and after a moment’s hesitation, flung it up into the tree where it snagged and hung. With luck, no one passing here would happen to glance up and see it. From the way he stared after it, I knew it had been precious to him.

I took up Myblack’s reins. ‘I’m going to mount,’ I told my captive. ‘Then I’m going to reach down and pull you up behind me. If you don’t cooperate, I’m going to knock you cold and leave you for those others. You know the ones I mean. The ones you thought we were, the killers from the village.’

He moistened his lips. The whole side of his face had started to puff and darken. For the first time, he spoke. ‘You aren’t with them?’

I stared at him coldly. ‘Did you even wonder about that before you shot at me?’ I demanded. I mounted my horse.

‘You were following our trail,’ he pointed out. He looked over at the woman he had shot and his expression was almost stricken. ‘I thought you were the villagers coming to kill us. Truly.’

I rode Myblack over to him and reached down. After an instant’s hesitation, he hitched his shoulder up towards me. I got a firm grip on his upper arm. Myblack snorted and turned in a circle, but after two hops, he managed to get a leg over her. I gave him a moment to settle behind me, and then told him, ‘Sit tight. She’s a tall horse. Throw yourself off her, you’ll likely break a shoulder.’

I glanced back the way we had come. There was still no sign of pursuit, but I had a sense of our luck running out. I looked around. The trail of the Witted led uphill, but I didn’t want to follow them further until I had wrung from this boy whatever he knew. My eyes plotted out a possible ruse. We could go downhill to where a stream probably flowed in winter. The moister soil at the bottom of the hill would take our tracks well. We could follow the old streambed for a time, then leave it. Then up the opposite side and across a rocky hillside and back into cover. It might work. Our tracks would be fresher, but they might just assume they were catching up. We might draw the pursuers off the Prince.

‘This way,’ I announced, and put my plan into action. My horse was not pleased with her double burden. She stepped out awkwardly as if determined to show me this was a bad idea.

‘But the trail…’ Laurel protested as we abandoned the faint tracks we had followed all day.

‘We don’t need their tracks. We’ve got him. He’ll know where they’re headed.’

I felt him draw a breath. Then he said, through gritted teeth, ‘I won’t tell.’

‘Of course you will,’ I assured him. I kicked Myblack at the same time that I asserted to her that she would obey me. Startled, she stepped out, and despite the added weight, she bore us both well. She was a strong and swift horse, but one accustomed to using those traits only as she pleased. We would have to come to terms about that.

I made her move fast down the hill and then pushed her along the stream until we came to a dry watercourse that met it. It was stony and that pleased me. We diverged there, and when I came to a rock-scrabble slope, we went up it. Behind me, the archer hung on with his knees. Myblack seemed to handle the challenge without too much effort. I hoped I was not setting too difficult a pace and course for Laurel. I urged Myblack up the gravelly hill at a steep angle. If I had lured the village mob into following us, I hoped this would present them with some nasty tracking.

At the top of the hill, I paused for the others to catch up. Nighteyes had vanished. I knew he rested now, gathering his strength to come after us. I wanted my wolf at my side, yet I knew he was in less danger by himself than in my company. I scanned the surrounding terrain. Night would be coming on soon, and I wanted us out of sight and in a defensible location, one that overlooked other approaches. Up, I decided. The hill we were on was part of a ridgeline hummocking through the land. Its sister was both higher and steeper, the rocks of her bones showing more clearly.

‘This way,’ I told the others, as if I knew what I was doing, and led them on. We descended briefly into a scantily wooded draw, and then I led them up again, following a dry streambed. Chance and good fortune blessed us. On the next hillside, I encountered a narrow game-trail, obviously made by something smaller and more agile than horses. We followed it. For a large horse, Myblack managed well, but I heard my captive catch his breath several times as the trail edged across the hill’s steep face. I knew Malta would make nothing of this. I dared not look back to see how Laurel was faring. I had to trust Whitecap to bear his mistress along.

My captive dared to speak to me. ‘I am Old Blood.’ He whispered it insistently, as if it should mean something to me.

‘Are you?’ I replied in sarcastic surprise.

‘But you are –’

‘Shut up!’ I cut his words off fiercely. ‘Your magic matters nothing to me. You’re a traitor. Speak again, and I’ll throw you off the horse right now.’