По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

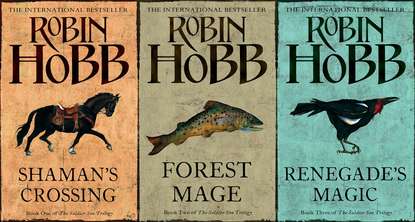

The Complete Soldier Son Trilogy: Shaman’s Crossing, Forest Mage, Renegade’s Magic

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

As he did at every evening meal, he asked each of his offspring in turn how we had employed our day. Rosse, my elder brother and the heir, had ridden down with our steward to visit the Bejawi settlement at the far north end of Widevale. The remnants of one branch of the formerly migratory people lived there at my father’s sufferance. When my father had first taken them in, the villagers had been mostly women, children and grandfathers too old to have fought in the Plains War. Now the children were young men and women, and my father wished to be sure they had useful tasks to occupy them and content them. There had been news from the Swick Reaches of an uprising of young warriors who had become discontented with settled ways. My father had no desire to see a similar restlessness in his nomads. He had recently gifted the Bejawi with a small herd of milk goats, and Rosse was pleased to report that the animals were thriving and providing both occupation and sustenance for the former hunters.

Elisi, my elder sister was next. She had mastered a difficult piece of music on her harp, and begun an embroidery of a Writ verse on a large hoop. She had also sent a letter to the Kassler sisters at Riverbend, inviting them to spend Midsummer week with us, planning a picnic, music, and fireworks in the evening of her sixteenth birthday. My father agreed that it sounded like a most pleasant holiday for Yaril and her and their friends.

Then it was my turn. I spoke first of my studies with my tutor, and then of my exercises with Duril. And then, almost as an afterthought, I mentioned that we had seen the messenger and cautiously added that I was very curious as to what could prompt such cruel haste. It was not quite a question, but it hung in the air, and I saw both Rosse and my mother hoping for an answer.

My father took a sip of his wine. ‘There is an outbreak of disease in the east, at one of the farthest outposts. Gettys is in the foothills of the Barrier Mountains. The messenger asks for reinforcements to replace the victims, healers to nurse the sick and guards to bury the dead and patrol the cemetery.’

Rosse was bold enough to speak. ‘It seems an urgent message and yet not, perhaps, one of such urgency to require the messenger to continue with the task himself.’

My father gave him a disapproving look. He obviously regarded rampant sickness and men dying in droves as inappropriate topics for discussion at table with his wife and young daughters. Quite possibly he considered it a military matter, and not a topic to be lightly discussed until King Troven had decided how best to deal with it. I was surprised when he actually replied to Rosse’s observation. ‘The medical officer for Gettys is, I fear, a superstitious man. He has sent a separate report, to the Queen, full of his usual speculations about magical influences from the native peoples of that region, stipulating that it not leave the messenger’s hand until he delivered it to her. Our queen, it is said, has an interest in matters of the supernatural, and rewards those who send her new knowledge. She has promised a lordship to anyone who can offer her proof of life beyond the grave.’

My mother made bold to speak, I think for the benefit of my sisters. ‘I do not regard such topics as appropriate for a lady to pursue. I am not alone in this. I have had letters from my sister and from Lady Wrohe, expressing the discomfort they felt when the Queen insisted they join her for a spirit-summoning session. My sister is a sceptic, saying it is all a trick by the so-called mediums who hold these sessions but Lady Wrohe wrote that she witnessed things she could not explain and it gave her nightmares for a month.’ She looked from Elisi, who appeared properly scandalized to Yaril, whose grey-blue eyes were round with interest. To Yaril, she added the comment, ‘We ladies are often considered to be flighty, ignorant creatures. I would be shamed if any of my daughters became caught up in such unnatural pursuits. If one wishes to study metaphysics, the first thing one should do is read the holy texts of the good god. In the Writ is all we need to know of the afterlife. To demand proof of it is presumptuous and an affront to the deity.’

That seemed properly to quench Yaril. She sat silent while my younger brother Vanze reported that he had worked on reading a difficult passage in the holy texts in the original Varnian and then meditated for two hours on it. When my father asked how Yaril had employed her day, she spoke only of mounting three new butterflies in her collection and of tatting enough lace to trim her summer shawl. Then, looking at her plate, she asked timorously, ‘Why must they guard the cemetery at Gettys?’

My father narrowed his eyes at her circling back to a topic he had dismissed. He answered curtly, ‘Because the Specks do not respect our burial customs and have been known to profane the dead.’

Yaril’s little intake of breath was so slight that I am sure I was the only one who heard it. Like her, my interest was more piqued than satisfied by my father’s reply, but as he immediately asked my mother how her day had progressed, I knew it was hopeless even to wonder.

And so that dinner came to a close, with coffee and a sweet, as all our dinners did. I wondered more about the Specks than I did about the mysterious plague. None of us could know then that the plague was not a one-time blight of disease, but would return to the outposts, summer after summer, and would gradually strike deeper and deeper into the western plains country.

During that first summer of contagion, awareness of the Speck plague slowly seeped into my life and coloured my concept of the borderlands. I had known that the farthest outposts of the King’s cavalry were now at the foothills of the Barrier Mountains. I knew that the ambitious King’s Road being built across the plains pushed ever closer to the mountains, but it was expected to take four more years to be completed. Since I was small I had heard tales of the mysterious and elusive Specks, the dappled people who could only live happily in the shadows of their native forest. Tales of them were, to my childish ears, little different to the tales of pixies and sprites that my sisters so loved. The very name of the people had crept into our language as a synonym for ‘inattentive’; to do a Speck’s day of work meant to do almost nothing at all. If I were caught day-dreaming over my books, my tutor might ask me if I were Speck-touched. I had grown up in the belief that the distant Specks were a harmless and rather silly folk who inhabited the glens and vales of the thickly forested mountains that, to my prairie-raised imagination, were almost as fantastic as the dappled folk who dwelt there.

But in that summer, my image of the Specks changed. They came to represent insidious disease, a killing plague that came, perhaps, simply from wearing a fur bought from a Speck trader or wafting one of the decorative fans they wove from the lace vines that grew in their forest. I wondered what they did to our graveyards, how they ‘profaned’ the dead. Instead of elusive, I now thought of them as furtive. Their mystery became ominous rather than enchanting, their lifestyle grubby and pest-ridden rather than primitively idyllic. A sickness that merely meant a night or two of fever for a Speck child devastated our outposts and outlying settlements, slaughtering by the score hearty young men in the prime of their youth.

Yet horrifying as the rumours of widespread death were to us, it was still a distant disaster. The stories we heard were like the tales of the violent windstorms that sometimes struck coastal cities far to the south of Gernia. We did not doubt the truth of them but we did not feel dread. Like the occasional uprisings amongst the conquered plainspeople, we knew they brought death and disaster, yet it was something that happened only on the new borders of the wild lands, out where our king’s horse still struggled to man the outposts, manage the more savage plainspeople and push back the wilderness to make way for civilization. It did not threaten our croplands and flocks in Widevale. Deaths from violence and privation and disease and mishap were the lot of the soldier. They entered the service, well aware that many would not live to retire from it. The plague seemed but another enemy that they must face stout-heartedly. I had faith that, as a people, we would prevail. I also knew that my current duty was to worry about my studies and training. Problems such as plainspeople uprising, Speck plagues and rumours of locusts were for my father to manage, not me.

In the weeks that followed, my father discouraged discussion of the plague, as if something about the topic were obscene or disgusting. His discouragement only fired my curiosity. Several times, Yaril brought me gossip from her friends, tales of Specks unearthing dead soldiers to perform hideous rites with the poor bodies. Some whispered of cannibalism and even more unspeakable desecration. Despite my mother’s discouragement, Yaril was as avariciously inquisitive about Specks and their wild magic as I was, and there were evenings when we passed our time in the shadowy garden, frightening one another with our ghoulish speculations.

The closest I came to having that curiosity indulged was one night the next summer when I overheard a conversation between my father and my elder brother Rosse. I was feeling a boy’s pique at being excluded from the domain of men. A scout had ridden in that morning and stopped to pass the day with my father. I had learned that he was taking his three-years leave, and intended to spend his three months of earned leisure in a journey to the cities of the west and back again. Scout Vaxton knew my father from years back, when they had served together in the Kidona campaign. They had both been young men then. Now my father was a noble and retired from the military, but the old scout toiled on for his king.

Scouts held a unique place in the King’s Cavalla. They were officers without official rank. Some were ordinary soldiers whose abilities had advanced them through the ranks to the duty of scouts. Others, it was rumoured, were noble-born soldier sons who had disgraced themselves, and had to find a way to serve the good god as soldiers without using their family names. There was an element of romance and adventure to everything I’d ever heard about scouts. Uniformed officers were supposed to treat them with respect, and my father seemed to hold Scout Vaxton in esteem, yet did not think him a worthy dining companion for his wife, daughters, and younger sons.

The grizzled old man fascinated me, and I had longed to listen to his talk, but only my eldest brother had been invited to take the noon meal with Scout Vaxton and my father. By mid-afternoon, the scout had ridden on his way, and I had looked longingly after him. His dress was a curious combination of cavalry uniform and plainspeople garb. The hat he wore was from an older generation of uniform, and supplemented with a bright kerchief that hung down the back of his neck to keep the sun off. I’d only glimpsed his pierced ears and tattooed fingers. I wondered if he’d adopted plainspeople ways in order to be accepted amongst them and learn more of their secrets, the better to scout for our horse soldiers in times of unrest. I knew he was a ranker, and truly not a fit dinner companion for my mother and sisters, and yet I had hoped that as a future officer, my father would include me at their meal. He hadn’t. There was no arguing with him about it, and even at dinner that evening he’d said little of the scout, other than that Vaxton now served at Gettys and found the Specks far more difficult to infiltrate than the plainspeople had been.

Rosse and my father had retired to my father’s study for brandy and cigars after dinner. I was still too young to be included in such manly pursuits, so I was walking off my meal with a sullen stroll about the gardens. As I passed the tall windows of the study, open to the sultry summer night, I overheard my father say, ‘If they indulge in filthy practices, then they deserve to die of them. It’s that simple, Rosse, and the good god’s will.’

The repugnance in my father’s voice brought me to a silent halt. My father was a man satisfied with his life, content with his land and his gentleman farming. He had survived his hard days as a soldier son and a cavalla officer, had risen to become one of King Troven’s new nobles and wore that mantle well. I seldom heard him speak with anger about anything, and even more rare was it to hear him so thoroughly disgusted. I drew closer to the house until I stood outside the gently blowing curtains and listened, aware that it was gravely rude to do so but still fascinated. Around me, the dry warm evening was filled with the chirring of insects from the fields.

‘Then you think the rumours are true? That the plague comes from sexual congress with the Specks?’ My brother, usually so calm a fellow, was horrified. I found myself creeping closer to the window. At that age, I had no personal experience of sexual congress at all. I was shocked to hear my brother and father bluntly speaking of such perversions as coupling with a lesser race. Like any lad of my years, I was consumed with curiosity about such things. I held my breath and listened.

‘How else?’ my father asked heavily. ‘The Specks are a vermin-ridden folk, living in the deep shadows under the trees until their skin mottles from lack of sunlight, like cheese gone to mould. Turn over a log in a bog and you’ll find better living conditions than what the Specks prefer. Yet their women, when young, can be comely, and to those soldiers of low intellect and less breeding they seem seductive and exotic. The penalty for such congress was a flogging when I was stationed on the edge of the Wilds. Distances were kept, and we had no plague.

‘Now that General Brodg has taken over as commander in the east, discipline is more lax. He is a good soldier, Rosse, a damn fine soldier, but blood and breeding have thinned in his line. He made his rank honestly and I do not begrudge him that, though some still say that the King insulted the nobly born soldier sons when he raised a common soldier to the rank of general. I myself say that the King has the right to promote whom he pleases, and that Brodg served him as well as any living man. But as a ranker rather than an officer born, he has far too much sympathy for the common soldier. I suspect he hesitates to apply proper punishment for transgressions that he himself may once have indulged in.’

My brother spoke but I could not catch his words. My father’s disagreement was in his tone. ‘Of course, one can sympathize with what the common soldier must endure. A good commander must be aware of the privations his men face, without condoning their plebeian reactions to them. One of the functions of an officer is to raise his men’s standards to his own; not to make so many allowances for their failings that they have no standards to aspire to.’

I heard my father rise and I shrank back into the shadows under the window, but his ponderous steps carried him to the sideboard. I heard the chink of glass on glass as he poured. ‘Half our soldiery these days are conscripts and slum scrapings. Some see little honour in commanding such men, but I will tell you that a good officer can make a silk purse out a sow’s ear, if given a free hand to do so! In the old days, any noble’s second son was proud to have the chance to serve his king, proud to venture into the wilds and drag civilization along in his footsteps. Now the Old Nobles keep their soldier sons close to home. They “soldier” by totting up columns of numbers and patrolling the grounds of the summer palace at Thares as if those were true tasks for an officer. The common foot soldiers are worse, as much rabble as troops these days, and I’ve heard tales of gambling, drinking and whoring in the border settlements that would have made old General Prode weep with fury. He never permitted us to have anything to do with the plainspeople beyond trade, and they were an honourable warrior folk before we subdued them. Now some regiments employ them as scouts, and even bring the females into their households as maids for their wives or nursemaids for their children. No good can come of that mingling, neither to the plainspeople nor us. It will make them hungry for all they don’t have, and envy can lead to an uprising. But even if it doesn’t come to that, the two races were never meant to traffic with one another in that way.’

My father was gathering momentum as he spoke. I am sure he did not realize that he had raised his voice. His words carried clearly to my ears.

‘With the Specks, it is even more true. They are a slothful people, too lazy even to have a culture of their own. If they can find a dry spot to sleep at night and dig up enough bugs to fill their bellies by day why, then they are well content. Their villages are little more than a few hammocks and a cook fire. Little wonder that they have all sorts of diseases amongst them. They pay such things no more mind than they do to the shiny little parasites that cling to their necks. Some of their children die, the rest live, and they go on breeding as happily as a tree full of monkeys. But when their diseases cross over to our folk, well … Well, then you have just what you have heard from that scout: an entire regiment sickened, half of them like to die, and the plague now spreading among the women and children of the settlement. And probably all because some low-born conscript wanted something a bit stranger or stronger than the honest whores at the fort brothel.’

My brother said something I could not quite hear, a query in his voice. My father gave a snort of laughter in reply. ‘Fat? Oh, I’ve heard those tales for years. Scare stories, I think, told to new troopers to keep them out of the forest edge of an evening. I’ve never seen one. And if the plague indeed works so, well, then, good. Let them be marked by it, so all may know or guess what they’ve been doing. Perhaps the good god in his wisdom chooses to make an example of them, that all may know the wages of sin.’

My brother had risen and followed my father to the sideboard. ‘Then you don’t believe,’ and I heard the caution in my brother’s voice, as if he feared my father would think him foolish, ‘that it could be a Speck curse, a sort of evil magic they use against us?’ Almost defensively, he added, ‘I heard the tale from an itinerant priest who had tried to take the word of the good god to the Specks. He was passing through the Landing on his way back west. He told me that the Specks drove him away, and one of their old women threatened that if we did not leave them in peace, their magic would loose disease amongst us.’

I, too, thought my father would laugh at him or rebuke him. But my father replied solemnly, ‘I’ve heard tales of Speck magic, just as you have, I’m sure. Most of those stories are nonsense, son, or the foolish beliefs of a natural people. Yet, at the bottom of each, there may be some small nugget of truth. The good god who keeps us left pockets of strangeness and shadow in the world he inherited from the old gods. Certainly, I’ve seen enough of plains magic to tell you that, yes, they have wind-wizards who can make rugs float upon the wind and smoke flow where they command it, regardless of how the wind blows, and I myself have seen a garrotte fly across a crowded tavern and wrap around the throat of a soldier who had insulted a wind-wizard’s woman. When the old gods left this world, they left bits of their magic behind for the folk who preferred to dwell in their dark rather than accept the good god’s light. But bits of it are all that they have left. Cold iron defeats and contains it. Shoot a plainsman with iron pellet, and his charms are worthless against us. The magic of the plainspeople worked for generations, but in the end, it was just magic. Its time is past. It wasn’t strong enough to stand against the forces of civilization and technology. We are coming up on a new age, son. Like it or not, all of us must move into it, or be churned into the muck under the wheels of progress. The introduction of Shir bloodlines to our plough horses coupled with the new split-iron ploughs has doubled what a farmer can keep under cultivation. Half of Old Thares has pipe drains now, and almost every street in the city is cobbled now. King Troven has put mail and passenger coaches on a schedule, and regulated the flow of trade on all the great rivers. It has become quite the fashion to travel up the Soudana River to Canby, and then enjoy the swift ride down on the elegant passenger jankships. As travellers and tourists venture east, population will follow. Towns will become cities in your lifetime. Times are changing, Rosse. I intend that Widevale change with them. A disease like this Speck plague is just a disease. Nothing more. Eventually, some doctor will get to the root of it, and it will be like shaking fever or throat rot. For the one, it was powdered kenzer bark, for the other, gargling with gin. Medicine has come a long way in the last twenty years. Eventually, a cure will be found for this Speck plague, or a way to avoid catching it. Until then, we mustn’t imagine it is anything more than an illness, or like a child turning a stray sock into a bugaboo under his cot, we’ll become too frightened of it to look at it closely.’ Almost as an aside, he added, ‘I wish our monarch had chosen a mate a bit less prone to flights of fancy. Her majesty’s fascination with hocus-pocus and “messages from beyond” has done much to spur the popular interest in such nonsense.’

I heard my brother’s lighter tread as he approached the window. He spoke carefully, well aware that my father tolerated no treasonous criticism of our king. ‘I am sure that you are right, Father. Disease must be fought with science, not charms and amulets. But I fear that some of the guilt for the conditions that welcome disease must be laid at our own door. Some say that our frontier towns have become foul places since the King decreed that debtors and criminals might redeem themselves by becoming settlers. I’ve heard that they are places of crime and vice and filth, where men live like rats amidst their own waste and garbage.’

My father was silent for a time, and I’ve no doubt that my brother held his breath, awaiting a paternal rebuke. But instead my father replied reluctantly, ‘It may be that our king has erred on the side of mercy with them. You would think that given the opportunity to begin anew, in a new land, all past sins and crimes erased, they would choose to build homes and raise families and leave their dirty ways behind. Some do, and perhaps those few are worth the trouble and expense of the coffles. If one man in ten can rise above a sordid past, maybe we should be willing to accept failure with the other nine as the price of saving the one. After all, can we expect King Troven to succeed with scum who will not heed even the teachings of the good god? What can one do with a man who will not reach out to save himself?’

My father’s voice had hardened, and I well knew what lecture would follow. He believed that a man determined his own fate, regardless of the class or circumstances he was born into. He himself was an example of this. He was the second son of a noble family, and thus society expected only that he become an officer in the military and serve his king and his country. And so he had, but with service so exemplary that he had been one of those the King had chosen to elevate to the status of lord. He was not asking of any man any more than that which he had demanded of himself.

I waited for him to explain this, yet again, to my brother, but instead it was my mother’s raised voice that reached my ears. She was calling to my sisters in their garden retreat. ‘Elisi! Yaril! Come in, my dears! The mosquitoes will make you all over blotches if you stay out much later tonight!’

‘Coming, Mother!’ my sisters called, their obedience and reluctance both evident in their tone. I did not blame them. Father had had an ornamental pond dug for them that summer, and it had become their favourite evening retreat. Strings of paper lanterns provided a pleasant glow without drowning out the stars above them. There was a small gazebo, the latticed walls laced with vines, and the walks around it had been landscaped with all sorts of fragrant night-blooming bushes. It had been quite an engineering project to find a way to keep the pond filled, and one of the gardener’s boys had to guard it nightly to keep the little wild cats of the region from devouring the expensive ornamental fish that now inhabited it. My sisters took great pleasure in sitting by the pond, weaving dreams of the homes and families that they would some day possess. Often I shared those evening conversations with them.

I knew that mother calling them meant that she would next be wondering what had become of me, and so I slipped from my hiding place and followed the gravel path around to the main door of our manor house and slipped inside and up to my schoolroom. I gave no more thought to the Speck plague at that time, but the next day I had many questions for Sergeant Duril about whether he thought the quality of foot soldiers had declined since the days when he and my father had served together along the borders. As I might have expected, he told me that the quality of the soldier directly reflected the quality of the officer who commanded him, and that the best way for me to ensure that those who followed me were upright was to be an upright man myself.

Even though I had heard such advice before, I took it to heart.

THREE (#ulink_504f5c83-de3d-5de5-92a8-d9acd0e40904)

Dewara (#ulink_504f5c83-de3d-5de5-92a8-d9acd0e40904)

The seasons turned and I grew. In the long summer of my twelfth year, it had taken all of Sirlofty’s patience and every bit of spring that my boyish legs possessed for me to fling myself onto his back from the ground. By the time I was fifteen, I could place my hands flat on my mount’s back and lever myself gracefully onto him without scrabbling my feet across him. It was a change that we both enjoyed.

There had been other changes as well. My scrawny, petulant tutor had been replaced twice over as my father’s requirements for my education had stiffened. I had two instructors now for my afternoon lessons, and I no longer dared to be tardy for them. One was a wizened old man with severely bound white locks and yellow teeth, who taught me tactics, logic, and to write and speak Varnian, the formal language of our ancient motherland, all with the liberal use of a very flexible cane that never seemed to leave his hand. I believe that Master Rorton’s diet consisted mostly of garlic and peppers and he nearly drove me mad by constantly standing at my shoulder watching every stroke of my pen as I hunched at my desk.

Master Leibsen was a hulking fellow from the far west who taught me both the theory and practice of my weapons. I could shoot straight now, both standing and mounted, with pistol and long gun. He taught me to measure powder as accurately by eye as most men could with a balance, and how to pour my own ball shot as well as maintain and repair my weapons. That was only lead ball, of course. The more expensive iron shot that had helped us defeat the plainspeople had to be turned out by a competent smith. My father saw no reason for me to be using it up on targets. From Master Leibsen I also learned boxing, wrestling, staves, fencing and, very privately after many entreaties on my part, to both throw and fight with knives. I relished my lessons with Leibsen as much as I detested the long afternoons with Master Rorton of the foul breath.

I had one other teacher in the spring of my sixteenth year. He did not last long and yet he was the most memorable of them. He stayed briefly, pitching his small tent in the shelter of a hollow near the river and never once approached the manor house. My mother would have been both terrified and offended if she had known of his presence, scarcely two miles away from her tender daughters. He was a plains savage and my father’s ancient enemy.

On the day I was to meet Dewara, I rode out innocently with my father and Sergeant Duril. Occasionally my father invited us on his morning rounds. I thought my ride that morning was such an outing. Usually it was a pleasant ride. We would move leisurely, lunch with one of his overseers, and halt at various cottages and tents to consult with the shepherds and the orchard workers. I took no more than I would usually carry on a pleasure ride. As the spring day was mild, I did not even take a heavy coat, but only my light jacket and my brimmed hat against the bright sunlight. The sort of country we lived in meant that only a fool set out on any ride unarmed. I carried no gun with me that day, but I did have a cavalry sword, worn yet serviceable, at my hip.

My father rode on one side of me, with Sergeant Duril on the other. It felt odd, as if they escorted me somewhere. The sergeant looked sullen. He was often taciturn, but his silence that day was weighted with suppressed disapproval. It was not often that he disagreed with my father about anything, and it filled me with both dread and intense curiosity.

Once we were well away from the house, my father told me that I would meet a Kidona plainsman that day. As he often did when we spoke of specific clans, my father discussed Kidona courtesy, and cautioned me that my meeting with Dewara was a matter for men, not to be discussed later with my mother or sisters, nor even mentioned in their hearing. On the rise above the plainsman’s camp, we halted and looked down upon a domed shelter made from humpdeer skins pegged to a wicker frame. The hides had been cured with the hair on so that they shed water. His three riding beasts were picketed nearby. They were the famous black-muzzled, round-bellied, striped-legged mounts that only the Kidona bred. Their manes stood up stiff and black as hearth brushes and their tails reminded me of a cow’s more than a horse’s. A short distance away, two Kidona women stood patiently next to a two-wheeled cart. A fourth animal shifted disconsolately between the shafts of the high-wheeled vehicle. The cart was empty.

A small smokeless fire burned in front of the tent. Dewara himself, arms folded on his chest, stood looking up at us. He did not notice us as we arrived; he was already standing, looking toward us, as we came into view. The man’s prescience made the hair on my arms stand up and I shivered.

‘Sergeant, you may wait here,’ my father said quietly.

Duril chewed at his upper lip, then spoke. ‘Sir, I’d rather be closer. In case I’m needed.’

My father looked at him directly. ‘Some things he cannot learn from me or from you. Some things can’t be taught to you by a friend; they can only be learned from an enemy.’